The Major Battles of the First World War

2013 RW Press Ltd

This 2013 edition published by RW Press Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission, in writing, of the publisher.

The views expressed in this book are those of the author but they are general views only, and readers are urged to consult a relevant and qualified specialist for individual advice in particular situations. The author and RW Press Ltd hereby exclude any liability to the extent permitted by law, for any errors or omissions in this book and for any loss, damage and expense (whether direct or indirect) suffered by a third party relying on any information contained in this book.

Although every effort has been made to trace and contact people mentioned in the text for their approval in time for publication, this has not been possible in all cases. If notified, we will be pleased to rectify any alleged errors or omissions when we reprint the title.

ISBN: 9781909284203

RW Press Ltd

RWPress@live.co.uk

www.rwpress.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

The battles of World War I were fought on an unprecedented scale. Both sides made use of industrial technology to inflict horrendous numbers of casualties on the other and armies composed of millions of men confronted each other in cataclysmic encounters, the like of which had never been seen before. On one side were the Central Powers of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, who were joined by the Turkish Ottoman Empire and by Bulgaria, while the other was made up of the Entente Powers, the Allies of France, Russia and Britain, together with the countries of the British Empire and Commonwealth, principally Canada, India, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Over the course of the war, other countries also joined the Allies, including Italy, Romania and, in April 1917, America, whose vast resources of manpower and huge industrial capacity dramatically altered the balance of power on the battlefield.

At the start of war in early August 1914 the expectation of the political and military leaders of all the countries involved was that it would be relatively short, over before the leaves fell, according to the Germans and, for Britain and France, over by Christmas. It would be, they thought, a mobile war in which each side attempted to outmanoeuvre the other, with the infantry used to break through the opponents front lines so that cavalry could serge through the breach to rout the enemy. In hindsight such opinions now appear hopelessly misguided, completely out of touch with the reality of modern warfare and relying on tactics that would not have been out of place in the Napoleonic Wars that were fought more than a hundred years beforehand. But technological and industrial advances had changed the nature of war just as they had changed almost every other facet of life by the beginning of the 20th century and, after initial phases of mobile war on both the Western and Eastern Fronts, the conflict quickly descended into deadlock, a stalemate of static trench warfare. Battlefields were dominated by rapid-firing and accurate artillery pieces and machine guns, and trench systems were protected by barbed wire, giving those armies occupying defensive positions an enormous advantage over those attacking them and leading to huge casualties among infantry units attempting frontal assaults the standard offensive tactic employed by both sides for the first few years of the war.

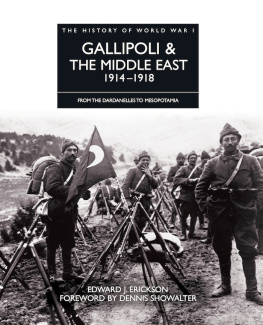

As the war progressed and it became ever more obvious that such tactics could not hope to break the stalemate, battlefield strategy slowly developed, making use of, for instance, small groups of specially trained storm troopers to infiltrate defences and the creeping barrage, an artillery bombardment which moved forward immediately in front of advancing infantry. The technology of warfare also moved on, including the use for the first time in warfare of poison gas, the aeroplane and, from 1916 onwards, the tank, which would eventually play an important role in breaking the stalemate. The Allies also attempted to open up other fronts in the war as a means of continuing the conflict without enduring the level of the casualties being inflicted on them in the terrible war of attrition of the Western Front. That was the thinking behind the ill-fated landings at Gallipoli, designed to knock Turkey out of the war but only succeeding in creating another stalemate of costly trench warfare in a different place. Much the same can be said for the other fronts in the war: in northern Italy, where the Italian army attempted to advance into Austrian-held territory in the Alps and towards Trieste; in the Middle East, where the British were trying to extend their sphere of influence against the Turks; and in the German colonial region of East Africa, where a small army held out against must greater British forces for almost the entire war. Meanwhile, the war at sea was mostly fought by means of a Royal Navy blockade of the ports of northern Germany and a U-boat war in the Atlantic in which the Germans attempted to prevent essential supplies from reaching Britain.

Over the course of the war, hundreds of battles were fought and, in the following pages, the major encounters are described and placed in the context of the overall situation of the war. By far the greatest number of these battles occurred on the Western Front, so the majority of the examples examined here come from this theatre of operations, including those of Verdun, the Somme and Passchendaele. But we also take a look at the other main theatres, including the Battle of Tannenberg on the Eastern Front, the Battle of Jutland at sea and the Gallipoli landings in Turkey. By taking this approach, what emerges is an overall portrait of the progress of that terrible war, told through its defining events, together with an appreciation of the battles themselves, some of which remain fixed in the public consciousness today, a hundred years after they were fought, as being the epitome of the horror and futility of war.

1914 The War Begins

On 28 June 1914, the 19-year-old Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in Sarajevo, the capitol of Bosnia, setting in motion an apparently unstoppable chain of events which culminated a month later in the outbreak of World War I. The reason why this individual murderous act led to one of the largest and most costly wars in human history has been the subject of intense and continuing debate ever since, without ever reaching a firm conclusion. In the preceding decade, there had been numerous incidents involving the major European powers of the day that had the potential to escalate into war, but which had been resolved by diplomatic means rather than through armed conflict and, at the time of the assassination, there appeared to be little expectation throughout Europe that this particular crisis could not be dealt with in the same way.

The Austrians blamed neighbouring Serbia for the assassination, not an unreasonable assumption because Princip belonged to a terrorist cell of a Serbian nationalist organization called Young Bosnia and had been armed and trained in Serbia by a secret society operating within its military and intelligence services. The overall aim of this secret society was to create the country of Greater Serbia, which would have included Bosnia, then under the jurisdiction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the assassination of Franz Ferdinand was part of its strategy to destabilize Bosnia in the hope of being able to exploit the ensuing chaos for its own ends. No evidence has ever come to light directly implicating the Serbian government in this conspiracy, but, nevertheless, at the time some form of response from the Austrians against Serbia appeared to be likely.

Next page