On 26 June 1897, on the occasion of Queen Victorias Diamond Jubilee, the sparkling waters of Spithead were alive with bustling activity with four lines, each stretching 5 miles in length, of great warships drawn up in review order at anchor under a cloudless sky.

The Prince of Wales, representing the queen, sailed between the long columns of warships aboard the Royal Yacht HMY Victoria and Albert as each in turn fired a twenty-one-gun salute.

The assembled fleet comprised more than 150 ships, including twenty-two battleships, the most powerful warships of their day, dressed overall with flags and resplendent in their Victorian paint scheme of black hulls, red boot topping, white superstructure, and buff masts and funnels.

The port line was led by the fleet flagship HMS Renown of the Royal Sovereign class, mounting four 13.5in guns and displacing 14,000 tons, together with the even more modern units of the Majestic class of similar displacement, but with better armour protection and armed with the new 12in 46-ton wire wound weapons, which gave greater penetrating power and accuracy together with a higher rate of fire.

Also present were more than forty cruisers, including the new first-class cruisers HMS Powerful and HMS Terrible, each of 14,600 tons and 100ft longer than the battleships, whose purpose was to protect merchant trade and hunt down would be commerce raiders.

Along with these giant vessels were the smaller second- and third-class protected cruisers, the maids of all work to carry the flag to all oceans of the world, the successors of the frigates of Nelsons day.

Among the smaller craft were twenty torpedo boats, the precursors to the later destroyers whose dashing exploits became legendary in two World Wars in the next century.

The inclusion of the submarine in the ranks of the Royal Navy was still three years away on that sunny afternoon, but the portent of change that all too soon would radically alter the structure of the service, its training and the design of the ships themselves was represented by the uninvited presence of Charles Parsons revolutionary steam-turbine propelled launch Turbinia, which, to the chagrin of the assembled high-ranking officers, raced up and down the lines at 30 knots in a demonstration of the superiority of this method of propulsion, while the naval steam pinnaces ineffectively tried to intercept this vision from the future.

This overwhelming display of naval might represented the high-water mark of empire and Great Britains predominance as master of the oceans of the world.

Since the Battle of Trafalgar almost one hundred years before, the Royal Navy had been the undisputed master of the waves. The British fleet was the sure shield that protected British trade and the Empire, and it was no empty boast, as stated in the Articles of War drawn up during the Dutch wars, that, It is upon the Navy, under the good Providence of God, that the safety, honour and welfare of this realm do chiefly depend.

The rattle of the anchor chain through the hawse pipe as a cruiser anchored in some foreign roadstead under the White Ensign was all that was necessary to project the awesome power of Great Britain, evoking awe and envy in equal measure, and regarded as guarantee of the Pax Britannica that protected our extensive overseas maritime trade, ensuring that our merchantmen could ply the oceans of the world in perfect safety.

During this period British supremacy at sea was unassailable. The following table demonstrates the comparative strengths in battleships of the great powers in 1897:

| Great Britain | France | Italy | Russia | Germany | U.S.A. | Japan |

| Built Bldg | Built Bldg | Built Bldg | Built Bldg | Built Bldg | Built Bldg | Built Bldg |

| 24 10 | 13 5 | 8 2 | 6 5 | 4 2 | 3 6 | 2 2 |

It will be seen from the table that only France anywhere near approached Great Britain in terms of battleship numbers. In the forty years since the Crimean War Great Britain had not been involved in a major European war, although conflict of colonial interests with France during the Scramble for Africa from the 1870s onward cast that country in the role of a potential future enemy. British military and naval defence strategy were therefore oriented towards this possibility.

As early as 1858, the launching of the 5,600-ton steam-powered ironclad Gloire and three later sister ships caused great concern to the Lords of the Admiralty, who controlled a fleet of Wooden Walls that had hardly evolved since Nelsons time. The immediate response by a hastily convened parliamentary committee was to recommend that, as an interim measure, several of the latest three-deckers should be cut down to two decks and converted to razee steam frigates, sheathed over with iron plating.

On further consideration, this was seen to be an inadequate panic response to the situation, and wiser counsels at that Admiralty reflecting on this expansion of French naval power requested revolutionary designs of armoured steam-powered ships from the Royal Dockyards and no fewer than twelve private shipyards.

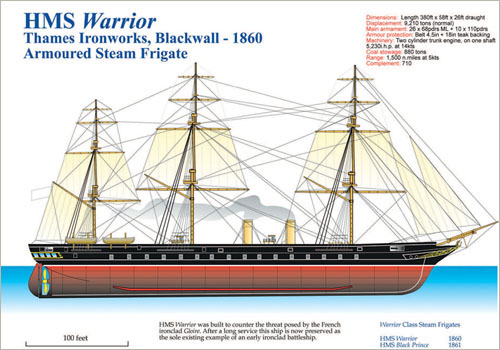

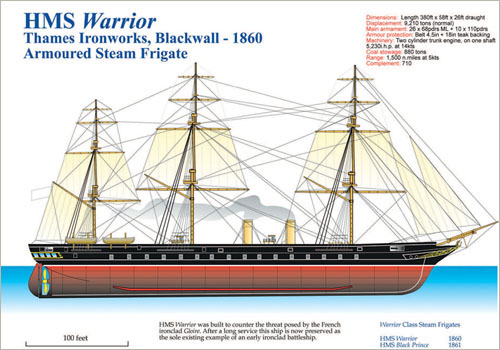

Following the results of the competition, the Naval estimates for 1858 set aside 252,000 for the construction of two large iron-framed armoured frigates. The first of these, HMS Warrior, was laid down at the Thames Ironworks at Blackwall in May 1859 and launched in December 1859, joining the Channel Fleet in October 1861, with her sister HMS Black Prince built on the Clyde a year later. In rapid succession, a further fourteen armoured frigates came down the ways between then and 1864.

At a stroke, the French attempt to steal a march over the Royal Navy had been effectively trumped, and faced with this overwhelming display of powerful warships ranged against them, the French Government decided that coming to some form of an understanding with their rival naval power offered a better solution than an arms race, and almost immediately there was a general improvement in Anglo-French relations.

Because of the abrupt change from wood to all-iron construction, new armoured frigates such as HMS Royal Oak, HMS Prince Consort and the Caledonia had a composite wood and iron construction in order to use up the vast stocks of timber stored in the Royal Dockyards.

The Warrior herself, although iron framed and clad, also benefited from a backing of 14in of teak, and was further protected along the waterline by twelve coal bunkers arranged on the outboard side of the two boiler rooms.

The Gloire was demonstrably a converted wooden three-decker that had been cut down to two decks and with iron plating fixed to her sides.

The Warrior, on the other hand, was revolutionary in design, having been built from the keel up, incorporating a more powerful armament, armour protection and propulsion system than her French rival.

Her displacement of 9,000 tons was almost twice that of the French ship and she was 367ft on the waterline, mounting originally a battery of 26 68pdr muzzle-loading smooth-bore cannon together with 10 110pdr breech-loading rifled Armstrong guns, and 4 70pdr breech-loading bow and stern chasers, disposed on the upper and lower gun decks in broadside fashion and protected by the 1,200 tons of armour in the ships sides.

Her machinery comprised a powerful two-cylinder horizontal trunk engine of 5,200hp built by John Penn and Co. at a cost of 79,400. Fed by steam from her two boiler rooms, this gave her a speed of 14 knots, with sufficient coal stowage for steaming 5,000 miles. Her three masts carried 36,000 sq. ft of canvas, plus an additional 18,000 sq. ft if studding sails were set, and with her screw lifted out of the water, with a favourable wind this press of canvas was capable of driving her at 12 knots on sail alone.