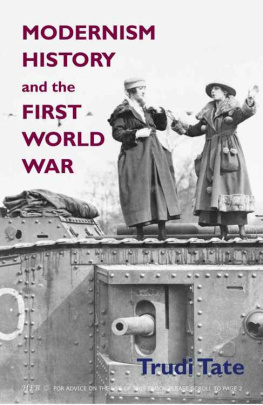

Frontispiece: Beatty and Babs, after investing 1,300 at the Chiswick Tank,

sang a song which was greatly appreciated.

Reproduced courtesy of the Trustees of the Imperial War Museum, London.

Crown copyright.

Modernism, History

and the First World War

Trudi Tate

HEB Humanities-Ebooks

1998, 2013, Trudi Tate

The Author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published by Manchester University Press 1998.

Second edition published in 2013 by Humanities-Ebooks, LLP

Tirril Hall, Tirril, Penrith CA10 2JE.

This book is available in Kindle format from Amazon, in paperback from Lulu.com, and as a Library PDF Ebook from MyiLibrary, EBSCO and Ebrary. The PDF, with page formatting and higher resolution images is available to individuals exclusively from

http://www.humanities-ebooks.co.uk.

No part of this publication may be otherwise reproduced or transmitted or distributed without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-84760-239-8 PDF

ISBN 978-1-84760-240-4 Paperback

ISBN 978-1-84760-241-1 Kindle

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

For the first edition, 1998

Many people have assisted me in the writing of this book. I am particularly grateful to Gillian Beer for her generous advice throughout the project and to Maud Ellmann for her encouragement and support. Thanks are due to Sue Cheshire, David Dickinson, Ian Donaldson, David Glover, Mary Hammond, Mike Hammond, Mary Jacobus, John Kerrigan, Vasant Kumar, Sarah Meer, Rod Mengham, Mark Micale, Peter Middleton, Ian Patterson, Lawrence Rainey, Suzanne Raitt, Karen Seymour, Helen Small, Hugh Stevens, John Tate, Toni Tate, Gill Thomas, Pam Thurschwell, David Trotter, the late Stephen Wall, and Jay Winter for comments and advice. The Modernism Seminar at the Centre for English Studies, London, has been a constant source of inspiration and debate; thanks to Claire Buck, Carolyn Burdett, Rebecca Dawson, Geoffrey Gilbert, and Lyndsey Stonebridge. The book could not have been completed without the intellectual support and warm generosity of Con Coroneos.

The staff of the University Library and English Faculty Library, Cambridge; the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh; the Hartley Library, University of Southampton; and the Imperial War Museum photographic department have been unfailingly courteous and helpful. Darwin College, Cambridge, and the Universities of Edinburgh and Southampton provide financial help with my research, and Clare Hall, Cambridge, provided me with a Visiting Fellowship and a lively environment in which to complete the writing in 1997.

Portions of chapter 1 were published in Sarah Sceats and Gail Cunningham, eds, Image and Power (London: Longman, 1996) and in Suzanne Raitt and Trudi Tate, eds, Womens Fiction of the Great War (Oxford: Clarendon, 1997); a version of chapter 2 appeared in Essays in Criticism (1997); parts of chapter 5 were published in Modernism/Modernity (1997) and Women: A Cultural Review (1997); a version of chapter 6 was published in Textual Practice (1994). Permission to reproduce the cover image and the plates in chapter 5 was kindly granted by the Trustees of the Imperial War Museum, London.

For the second edition, 2013

Thanks to colleagues and students at Clare Hall, where I was elected a Fellow in 2001, and to the Faculty of English, Cambridge, for their bright and supportive intellectual environments. Colleagues and students in the Institute for English and American Studies at the J. W. Goethe University, Frankfurt, provided insightful comments on this work; thanks to Daniel Dornhofer, Astrid Erll, Klaus Hofmann, Stefanie Lotz, and Harald Raykowski. Thanks also to Gillian Beer, Evelyn Chan, Santanu Das, Alison Hennegan, Alex Houen, Jane Potter, Hugh Stevens, and Bobbie Wells for continuing conversations and wise advice. I am particularly grateful to Irene Hills and Klaus Hofmann for their kind help in preparing this second edition of the book. Finally, heartfelt thanks to Rosa Tate for making it all worthwhile.

Permission to reproduce the cover image and the plates in chapter 5 was kindly granted by the Trustees of the Imperial War Museum, London.

Introduction

In a scene excised from The Years (1937), Virginia Woolf describes a group of passengers sitting on the London Tube in 1914, desperate for news of the war. Three British Cruisers Sunk, they read, and they scramble through the newspaper, looking for more information. But there is no more news, only items: triplets born, strawberries picked, that was all. As time passed, many writers struggled to express what they had seenor not seenin the event that was to shape the history of the entire twentieth century.

This is a study of the relationship between modernist fiction, the First World War, and cultural history. It explores the ways in which writing attempted to bear witness to the trauma of the war and its consequences. All the works I will discuss are concerned with the distinction between witnessing and seeing, and they worry about how one is placed in relation to a history one has lived through and not seen, or seen only partially, through a fog of ignorance, fear, confusion, and lies. This question troubled combatants as well as civilians, and the chapters of this book read across a range of writings: by soldiers and nurses (Barbusse, Blunden, Remarque, Borden, Manning, and others) and civilians such as Woolf, HD, Lawrence, Kipling, and Faulkner. While the discussion focuses on literature produced in Britain during and after the war, it also looks at fiction from other countries which was influential in Britain: the best-selling soldiers narratives of Barbusse ( Under Fire , 1916) and Remarque ( All Quiet on the Western Front , 1929), and Soldiers Pay (1926), William Faulkners first novel which appeared in Britain in 1930 and was championed as a war novel by Arnold Bennett. I am interested in the ways in which the different writings interact, and how they take up ideas which circulated in other, non-literary writingsin politics, medicine, psychoanalysis, propaganda, and in the newspapers.

One aim of this study is to rethink the ways we read modernism. The term itself is imprecise and much contested, yet it remains a useful description of the writings which were self-consciously avant-garde or attempting to extend the possibilities of literary form in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet modernists and war writers reviewed one anothers books, and war writings were discussed in avant-garde journals such as the Little Review and the Egoist . Reading them together, the distinction between modernism and war writing starts to dissolveand was by no means clear at the timeand modernism after 1914 begins to look like a peculiar but significant form of war writing.

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that we cannot understand the events at the end of the twentieth century unless we know about its beginnings. This applies to literary history as well as to politics and international relations. The literature of the early twentieth century, both modernist and non-modernist, helps us to think about how cultures imagined themselves in this period of specific crisis. In Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning , J. M. Winter points out that the war was commemorated in many different ways, many of which look back to nineteenth-century traditions, and not forwards or sideways to modernism. Yet there is more dialogue between modernism and other cultural activities of the period than Winter allows for in his argument. What interests me are the ways in which the literature, including modernism, actively engages with other acts of commemoration, memory, and analysis of the war.