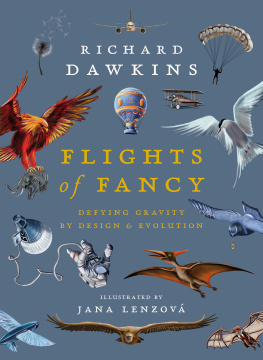

FLIGHTS OF FANCY

A Delacorte Press Book

PUBLISHING HISTORY

Random House UK hardcover edition published 2007

Delacorte Press hardcover edition / November 2008

Published by

Bantam Dell

A Division of Random House, Inc.

New York, New York

All rights reserved

Copyright 2007 by Peter Tate

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.,

and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tate, Peter.

Flights of fancy : birds in myth, legend and superstition / Peter Tate.

p. cm.

Originally published: London : Random House, 2007.

eISBN: 978-0-307-78397-4

BirdsFolklore. BirdsMythology. I. Title.

GR735.T37 2008

398.24528dc22

2008023169

www.bantamdell.com

v3.1

For Anne

Contents

Introduction

From the significance of the first cuckoo to rhymes about magpies, an astonishingly large and varied body of folklore has grown up around birds. Some of the stories that have been handed down through the generations are quite straightforward, such as the belief that its bad luck to kill a robin. Others are amazingly elaborate or bizarre, such as the Greek folk-cure for a headache, which involved removing the head of a swallow at the full moon, then leaving it in a linen bag to dry. They can be found in all parts of the world, from the story of Yorimoto in Japan, who hid from his enemies in a tree and was protected by two doves, to the strange tale of Gertrude in Germany, who was turned into a woodpecker as punishment for her miserliness. What they all show is just how fascinated mankind has always been by birds. They are, after all, creatures that occupy a very particular and unusual place in our lives. On the one hand, they seem very familiar: they build nests in our gardens or in the eaves of our houses; some have even been domesticated and play an important role in agriculture to this day. On the other hand, they also inhabit a completely different realm from our own one that we land-bound creatures can only imagine and wonder at. It seems scarcely surprising, therefore, that they should have proved such a rich source of speculation and myth-making.

What I have tried to do in this book is not to attempt an exhaustive survey of traditional beliefs about birds such a survey would take up many hundreds of pages but to select the stories that have most intrigued me in the course of a lifetimes study. For example, I knew that migration was not fully understood before the eighteenth century, but I was fascinated to discover that many people used to believe that cuckoos turned into hawks when they departed for the winter months. Im also intrigued by stories that recur in different traditions. The belief that birds with black plumage, such as crows and ravens, originally had white feathers but were punished for some crime or other, for example, is very widely spread. Similarly, tales of swan maidens can be found as far afield as India, Greenland and Ireland. Perhaps the strangest example of a well-travelled tale is that told of cranes. I first came across the belief that every winter migrating cranes do battle with pygmies in Aristotles History of Animals. I was astonished, years later, to come across precisely the same story among the Cherokees of the south-eastern USA. I still have no idea how the same story came to be told in places so many thousands of miles apart.

Of course, many of the stories recorded here were almost certainly told just for fun originally. Some, no doubt, were old wives tales, told to scare or instruct youngsters. Some reflect peoples desperate desire to control the present or foretell the future through natural signs such as the belief in Snowdonia that circling eagles portended victory on the battlefield. One story, however, can lay good claim to having a place or at least a footnote in history. It concerns the barnacle goose, which in medieval times was variously described as a bird or, thanks to some rather confused travellers tales, as a sort of fish that hatched from barnacles. Since Catholic countries had strict rules on what could be eaten when, the barnacle goose debate was eventually picked up by the Church, and in 1215 one of the most powerful of all medieval popes, Innocent III, felt compelled to weigh in and make a judgement on the matter at the Fourth Lateran Council. Its a nice reminder of how central to peoples lives story-making can be.

My thanks go to my agent Charlotte Vamos, without whom this book would never have taken flight. I would also like to thank the editorial team at Random House: Nigel Wilcockson, Caroline Pretty and Sophie Lazar.

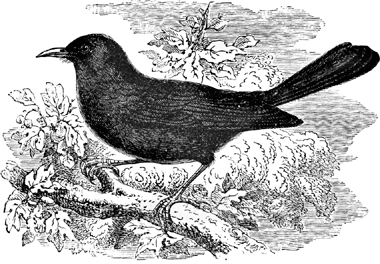

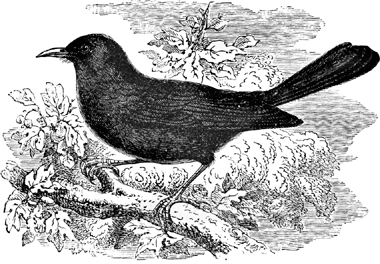

Blackbird

(Turdus merula)

A rather plump species of thrush with very obvious differences between males and females. The male blackbird lives up to its name and has black feathers with a bright orange bill, while the female is mainly dark brown. Related to what in the US are called robins (Turdus migratorius), it is one of Northern Europes most familiar birds, and can be found in most gardens and parks. Its song is clear, beautiful and distinctive, making blackbirds one of the most recognizable songsters.

Like so many birds with a black plumage, blackbirds were once thought to have been white. In Brescia in Italy, for example, it was believed that the blackbird changed colour as a result of a cruel and cold winter. Forced to take shelter from the wind and snow, the bird sought refuge in a chimney, where it became blackened by the soot. In commemoration, the last two days of January and the first of February became known as i giorni della merla, the blackbird days. White blackbirds can also be found in ancient Greek tradition: Aristotle describes them in his History of Animals as living on Mount Cyllene in Arcadia. These mythical birds were supposed to have a wider range of notes than other blackbirds and to appear only by moonlight.

An alternative legend was recorded by the nineteenth-century French author Eugene Rolland. It tells how a white blackbird, while lurking in a thicket, was greatly astonished to discover a magpie hiding diamonds, jewellery and golden coins in her nest. Upon asking the magpie how he too might acquire such a treasure, he received the reply:

You must seek out in the bowels of the earth the palace of the Prince of Riches, offer him your services and he will allow you to carry off as much treasure as you can carry in your beak. You will have to pass through many caverns each more overflowing with riches than the last, but you must particularly remember not to touch a single thing until you have actually seen the Prince himself.

The blackbird immediately went to the entrance of the subterranean passage to discover the treasure. The first cavern he had to pass through was lined with silver, but he managed to keep the magpies advice in mind and continue on his way. The second cavern was ablaze with gold, and though the blackbird tried to master himself, it proved too much for him and he plunged his beak into the glittering dust with which the floor was strewn. Rolland continues:

Immediately there appeared a terrible demon vomiting fire and smoke who rushed up to the wretched bird with such lightning speed that the bird escaped with the greatest difficulty. But alas the thick smoke had besmirched forever his white plumage and he became as now, quite black with the exception of his bill which still preserves the colour of the gold he was so anxious to carry off.