Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the Doughboys, who rest eternally Over There

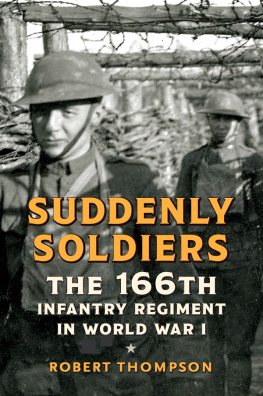

The war that began in Europe in 1914 was known at the time as the Great War, the World War, or simply the war. Among Allied troops, German soldiers on the other side of the front were called Jerry, Huns, Fritz, ormostly by the Frenchboche. British troops were nicknamed Tommies, and French soldiers, many of whom wore thick mustaches or beards, were nicknamed poilu (hairy one[s]).

When America entered the war, its forces deployed to France were collectively known as the American Expeditionary Forces, or AEF. Its uniformed troopsincluding soldiers and Marineswere called Yanks, Sammies, and most commonly doughboys. Doughboys in France were said to be over there. Though the precise origin of doughboy remains uncertain, the nickname was employed extensively in rallying posters, songs, and literature. Among Allied nations, doughboy was used flatteringly, and over there became a patriotic rallying slogan. The reader will also notice that men appears often to collectively refer to troops or soldiers, reflecting the all-male Army of 19171918.

The source for every quotation in this book is cited in the Notes, except for successive quotes in the same paragraph from the same source. In the interest of clarity, spelling and punctuation errors have been corrected in the original quotations to avoid adding the intrusive [ sic ], and all spelling corrections are specifically listed in the Notes.

US Army Ranks and Unit Structure,

19171918

During World War I, US Army ranks and units were organized as follows:

SOLDIER

SQUAD: 9 to 17 soldiers, usually led by a corporal or sergeant

PLATOON: 4 to 5 squads, 60 soldiers, usually led by a lieutenant

COMPANY: 4 platoons, 250 soldiers, usually commanded by a captain

BATTALION: 4 companies, 1,030 soldiers, usually commanded by a major or lieutenant colonel

REGIMENT: 3 battalions, plus a machine-gun company, approximately 3,700 soldiers, commanded by a colonel

BRIGADE: 2 infantry regiments, plus a machine-gun battalion, approximately 8,400 soldiers, commanded by a brigadier general

DIVISION: 2 brigades, plus a field artillery brigade, an engineers regiment, a machine-gun battalion, and a signal corps company, totaling approximately 28,000 soldiers, commanded by a major general

CORPS: 2 to 6 divisions

ARMY: 3 to 5 corps

No one with a heart in his breast, no American, no lover of humanity, can stand in the presence of these graves without the most profound emotion. These men who lie here are men of a unique breed. Their like has not been seen since the far days of the crusades. Never before have men crossed the seas to a foreign land to fight for a cause which they did not pretend was peculiarly their own, but knew was the cause of humanity and of mankind.

PRESIDENT WOODROW WILSON, speaking on Memorial Day,

May 30, 1919, at the first of many US cemeteries in France dedicated to Americas fallen in the World War.

The fourth winter of the World War lingered throughout northern France on Tuesday, April 16, 1918, reluctant to give way to spring. Mercury hovered in the low forties at midmorning under an overcast, almost colorless sky, shaping what one officer described as a cold, bleak April day. The persistent cold was especially discomforting to the division commander, Major General Bullard, who suffered from neuritis that shot debilitating pain through his right arm and left him shivering with chills even on warm days.

Standing before the three-story chateau serving as his temporary Division Headquarters, Bullard eyed the long approach road for the distinctive four-star command car of his boss, the Big Chief, Gen. John Black Jack Pershing. Ever the field commander, Bullard stood informally in dusty, spurred riding boots and khaki soft-sided cap, the two-star rank on his shoulders concealed by his bulky wolfskin coat. At his side, a handful of staff officers stood braced in anticipation, polished in Sam Browne belts under buttoned-up, sleek olive overcoats. General Pershing was on his way to address the divisions officers, and Bullard, knowing the Big Chiefs impatience for sickly commanders, concealed his physical agony and forced a display of complete health.

A West Pointer from Alabama, fifty-seven-year-old Robert Lee Bullard was slim and refined. He stood five feet ten inches tall, and his clear blue eyes peered warmly from a pale face of delicate features, with short, frosted wisps of brown hair poking out from under his cap. His reading glasses appeared instantly when there was a map to be studied or memorandum to be reviewed, underscoring an erudition that more closely resembled a professor than an Army commander. But a highly informal and energetic command style belied his patrician appearance, and he drove his troops hard.

Bullard commanded the 28,000 soldiers of the US Armys 1st Division, celebrated the previous summer as the first doughboys to land in France after Americas entry into the war. By fall, they had earned the distinction of being the first in the trenches, the first to fire a shot at the Germans, and the first to suffer combat casualties. In the bitter cold of January, as other fresh divisions of the AEF (American Expeditionary Forces) were trickling into France for training, Bullard led his troops into the front lines of an active sector, gaining for them indispensable experience under fire and fixing a fighting institutional tone.

Despite the neuritis that stung his shoulder and arm and hampered him with insufferable cold spells, Bullard remained an unbroken presence in the field by his men through the stretch of winter conditions so harsh many called it the Valley Forge of the War. In the privacy of his headquarters, staff officers occasionally spotted him wrapped in blankets in front of a roaring fire, but before his soldiers he forced a stoic faade betrayed only by a strained expression and a clench-fisted right arm slung in the grip of his left hand. Bullard believed the best officer was ready to do and to bear all that his men do and bear, and in living thisand through his folksy, courteous leadership stylehe quickly earned the affection of his men.

* * *

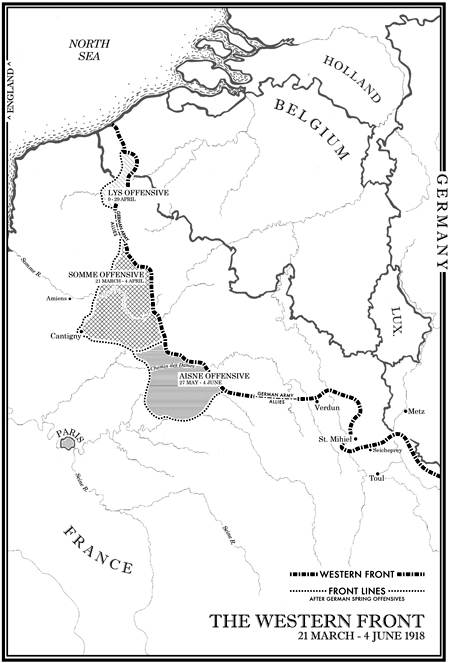

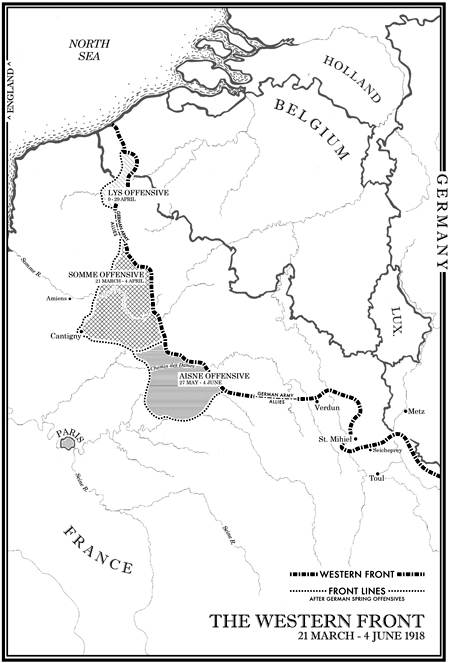

Three weeks earlier, a massive German offensive forced Allied lines back forty miles, the most alarming movement yet on a Western Front marked by three and a half years of strategic rigor mortis. In the face of this great crisis, General Pershing offered French General Ferdinand Fochthe Supreme Allied Commanderall that we have. Of the five American divisions in France, Pershing ordered his favored 1stwhich he openly regarded as the brightest star in the AEFs expanding constellationto the front to help stem the German tide. Thirteen months after America entered the war and ten months after landing in France, Bullards troops were finally headed into battle.