2003 Modern Library Paperback Edition

Copyright 1965, 1966 and copyright renewed 1993, 1994 by John Toland

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Modern Library, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

M ODERN L IBRARY and the T ORCHBEARER Design are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This work was originally published in hardcover by

Random House, Inc. in 1966.

ISBN 0-8129-6859-X

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8041-8094-8

The author is grateful to the following for permission to quote:

DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC .: From Triumph in the West, Arthur Bryant. Copyright 1959 by Arthur Bryant.

A. D. PETERS & COMPANY : From The Testament of Adolf Hitler:

The Hitler-Bormann Documents, FebruaryApril, 1945, edited by H. R. Trevor-Roper. Published by Cassell & Company, Ltd.

TIME , INC .: From Memoirs by Harry S. Truman, Vol. I, .

Published by Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1955 by Time, Inc.

WEIDENFELD & NICOLSON : From The Bormann Letters: The Private Correspondence Between Martin Bormann and His Wife, from January 1943 to April 1945, London, 1954.

Modern Library website address: www.modernlibrary.com

v3.1

C ONTENTS

A UTHOR S N OTE

Perhaps no other 100 days in history have had greater significance and consequences than those at the end of World War II in Europe. Within the space of three months Roosevelt, Hitler and Mussolini died, as did Nazism and Fascism. V-E Day marked the end of one era and the beginning of another, with its fantastic hopes and terrors.

I have tried to write of those portentous days as if they took place a hundred years ago and to portray Hitler, Himmler, Gring and their kind not against the background of one who lived through that period but with the objectivity of time.

The book is based on hundreds of interviews with people from twenty-one countries who were directly involved with the events described. Wherever possible the participants are the basic source for what happened and they revealand at times condemnthemselves with their own words. It is time for revelation, not accusation.

The book is further based on several thousand primary sources: after-action reports; staff journals and monographs; a number of top-secret messages and personal documents that have until now been unavailable to historians (Lieutenant General Hobart Gay, Pattons chief of staff, for example, allowed his diarykept at Pattons orderto be used for the first time); finally, numerous published and unpublished books were consulted.

The excerpts of dialogue in this book are not fictional. They come from transcripts, stenographic notes and the memory of the participants. The Notes (at the end of the book) contain sources for all the material used, chapter by chapter.

Max Beerbohm once wrote, The past is a work of art, free of irrelevancies and loose ends. My hope has been to re-create past events after enough time had elapsed to recollect them in relative tranquillity, but not before the irrelevancies and loose ends, which are the spice of history, have disappeared.

PART ONE

The Great Offensive

1

Floodtide East

.

On the morning of January 27, 1945, there was an air of restrained excitement among the 10,000 Allied occupants of Stalag Luft III (Air Prisoner of War Camp) at Sagan, only 100 air miles southeast of Berlin. In spite of the biting cold and the steady fall of snow in large flakes, prisoners huddled outside their barracks discussing the latest report: the Russians were less than twenty miles to the east and still advancing.

Two weeks earlier the first news of a great Red Army offensive had begun seeping into the camp from anxious guards. The prisoners were in high spirits until several goonsguardshinted that orders had come from Berlin to make the camp a Festung, a hedgehog fortress to be defended to the end. A few days later another rumor spread that the Germans were going to use the Kriegies (short for Kriegsgefangenen, war prisoners) as hostages and shoot them if the Russians tried to take the area. This story was succeeded by an even more terrifying one: the Germans were going to convert the showers into gas chambers and simply exterminate the prisoners.

Morale dropped so alarmingly that Arthur Vanaman, an American brigadier general and the senior Allied officer at Sagan, sent a directive to the camps five compounds urging that all rumors be stopped and that preparations for a possible forced march to the west be accelerated.

One of the prisoners wrote in his diary, Our barracks looks like a gathering of the Ladies Aid Sewing Circle. Men sat cross-legged on the bunks cutting glove patterns from the bottoms of overcoats, devising snow caps and face guards, and improvising knapsacks out of trousers. A few ambitious ones were even building sleds from odd bits of lumber and bed boards.

But nothing could stop the rumors, and on January 26 Vanaman called a meeting in the camps largest auditorium. He strode up to the stage and announced that he had just learned from a BBC news report over a contraband radio that the Russians were only twenty-two miles away. He quieted the cheers and said they would all probably be marched across Germany. Our best chance of survival is to stand together as one team, ready to face whatever may come. God is our only hope and we must trust him.

By the morning of January 27 the prisoners of Sagan were ready. Evacuation kits were stacked near the doors of each barracks. Other equipment lay on the bunks, ready for hasty packing. As the snow piled up, the men waited watchfully, with a strange feeling of peace and calm. Many kept looking out past the high wire fences at the even rows of snow-laden pine trees. Beyond lay the unknown.

.

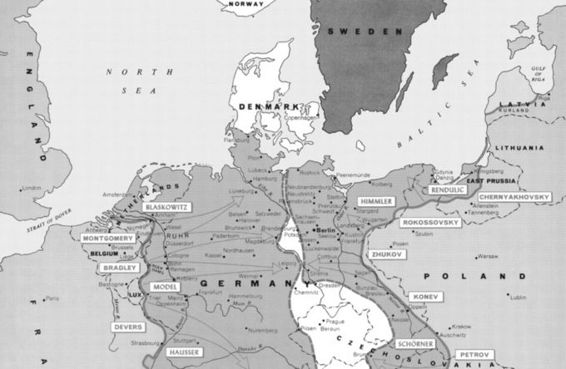

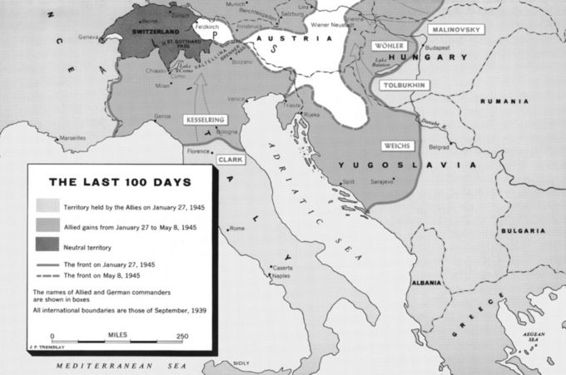

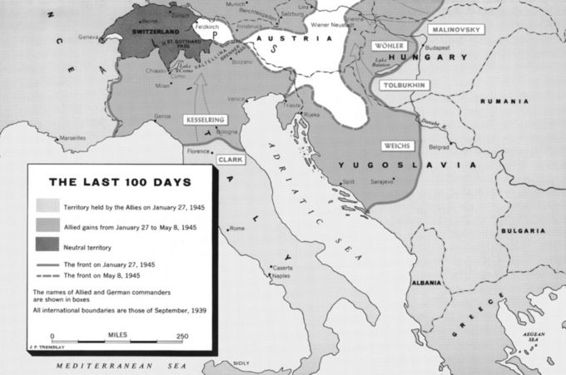

Once Hitler held almost the entire land mass of Europe as well as North Africa. His troops had ranged deep into Russia and controlled more territory than the Holy Roman Empire. Now, after nearly five and a half years of war, his vast empire was compressed to the very borders of Germany. The combined American, British, Canadian and French armies were poised for the final assault along the Fatherlands western boundary from Holland to Switzerland. And the sprawling eastern front, extending from the warm waters of the Adriatic Sea to the icy Baltic, was being punctured at a dozen points. After liberating half of Yugoslavia, most of Hungary and the eastern third of Czechoslovakia, the Red Army was already in the fifteenth day of the greatest offensive in military history.