Table of Contents

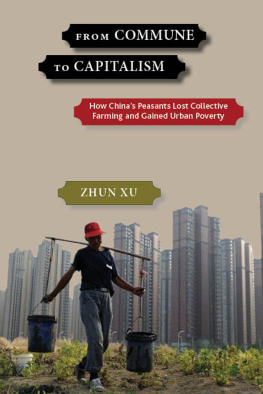

RED CHINAS GREEN REVOLUTION

Red Chinas Green Revolution

TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION, INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE, AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT UNDER THE COMMUNE

Joshua Eisenman

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Joshua Eisenman

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54675-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Eisenman, Joshua, 1977- author.

Title: Red Chinas green revolution: technological innovation, institutional change, and economic development under the commune / Joshua Eisenman.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017054574 | ISBN 9780231186667 (hardcover and pbk.: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Green RevolutionChina. | Communes (China) | AgricultureEconomic aspectsChina. | Agriculture and stateChina.

Classification: LCC S471.C6 E37 2018 | DDC 338.10951dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017054574

ISBN 978-0231-18666-7 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0231-18667-4 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0231-54675-1 (e-book)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Noah Arlow

To the memory of Richard Baum, who taught me how to seek truth from facts.

CONTENTS

BY LYNN T. WHITE III

This book offers a startling new analysis of Chinas most important local institution in Maos time, the peoples commune. In particular, it explores the least-well-reported years of recent Chinese history, the 1970s, when the countrys so-called economic rise began. Most officials, journalists, and scholars still treat that institution and decade as simply radical and backward looking. Most of the 1970s is described misleadingly in many books as part of a basically homogeneous Cultural Revolution, before China began to prosper. The commune as an institution was indeed a failure after 1958, bringing famine and poverty to millions; so most writers presume it remained an economic and political failure until it was abolished during the few years after Deng Xiaoping became Chinas supremo in 1978.

To the contrary, Joshua Eisenman shows that after 1970 Chinas communes, production brigades, and production teams became crucial generators of rural prosperity. He uses new sources, presenting statistics to prove that rural productivity grew quicklynationwidein the 1970s. This achievement occurred not just in a few selected and traditionally rich regions, such as Jiangnan and Guangdong, where a few previous writers had noticed. Instead, this productivity was widespread in many parts of the country. Eisenman presents data from eight major provinces, and from China as a whole, demonstrating that rural production from the early 1970s rose rapidly per commune member, per land unit, and in total. These findings refute the conventional, quasi-official story, which holds that before 1978 Chinas rural (as distinct from urban) economy was in dire straits, requiring neoliberal efficiencies to fix it. Eisenmans revisionist book offers hard data that disprove that conventional understanding. Communes, brigades, and teams bred more successful local leaders and entrepreneurs than practically anybodyincluding Deng Xiaoping, economists, or othersthought possible.

Maoist communes, with support from some central and local leaders, created Chinas green revolution. This change was supported by material elements (high-yield seeds, multi-cropping, controlled irrigation, agricultural extension, and high rates of rural saving and investment). These factors were also supported by strong communalist values. Most sources have defined Chinas reform as a post-1978 phenomenonand have attributed it mainly to market efficiency. This usual periodization of the start of the economic surge begins nearly a decade too late. Change in the places where most Chinese livedthe countrysidehave largely been ignored. CommunalistMaoist norms, as well as the improved agronomy that they sustained, brought more prosperity to the fields in which hundreds of millions of Chinese toiled during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

For the majority of Chinese, who tilled land, the 1970s was not a lost decade. Intellectuals, who write history, indeed had a grim time. But Eisenman chronicles in the early 1970s a quick increase of rural electric generators, walking tractors, fertilizers, trucks, pumps, and tool shops in which to repair them. He points out that the Northern Districts Agricultural Conference, held in 1970, spread the green revolution to new areas. Agricultural extension and mechanization changed China well before 1978. This book offers extensive statistics on these concrete, situational factors of changebut it equally treats the communalist ideals and management organizations that supported these material inputs to the new agronomy, and then to rural factories.

The commune was the church of Mao. Songs about Mao as savior of the East; dancers waving his Little Red Book; and posters of ardent workers, badges, and icons of the chairman demonstrated far more intense personal commitments than contemporary modern people generally muster for any cause. Such rituals are often derided in Western publications, yet a religion of this sort reduces moral hazard problems that are inherent in communitarian projects. Maoist norms shamed free-riding and flight from field labor.

Eisenman fully reports the coercive aspects of this form of organization; his treatment of commune militias is more complete than any other. Enforcement of the urban household registration system meant that Sent-Down youths or ambitious peasants could not move easily into big cities. Thus, brain drain from the countryside was discouraged. The commune was militarized at a time when China was trying to balance threats that national leaders perceived from both the Soviet Union in the north and the United States in Vietnam. Maoist enthusiasm and more responsive remuneration systems were essential to increased commune productivity.

Eisenman explores the comparative history of communes in diverse cultures, ranging far from China, to Pietists, Shakers, Owenists, kibbutzim, and other examples. Such organizations are not always successful in serving their membersbut under some conditions, they are so. The book gives due attention also to the histories of high-modernist communes (e.g., in the Soviet Union) and to reasons for their various failures and successes. But in China during the 1970s at least, this book proves that communes, brigades, and teams brought more wealth to places that had been poor.

What made farmers work productively? Three main factors emerge from the data: Tillers need capital (including tools embodying technology). They need normative incentives to work hard rather than shirk work. They need to be organized in units that are small enough to achieve face-to-face trust but large enough to ensure that resources join their labor. These three themes unify the book and adapt its structure for comparative study of work contexts anywhere.

New insights emerge from findings about all three of these themes, notably the organizational one. Eisenman uses state-of-the-art statistical analyses to show that having many brigades per commune and many households per team usually meant higher productivity. Also, output rose when relative commune size was small. He offers explanations for these new discoveries, which all are available in this book for the first time.