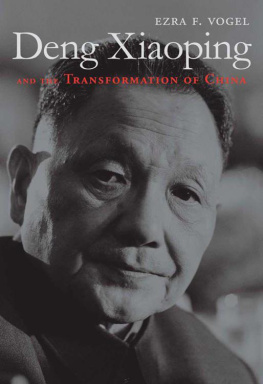

Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China

EZRA F. VOGEL

THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

2011

Copyright 2011 by Ezra F. Vogel

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vogel, Ezra F.

Deng Xiaoping and the transformation of China / Ezra F. Vogel.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-05544-5

1. Deng, Xiaoping, 19041997. 2. Heads of stateChinaBiography. 3. ChinaPolitics and government19762002. I. Title.

DS778.T39V64 2011

951.05092dc22

[B] 2011006925

ISBN 978-0-674-06283-2 (electronic)

To my wife, Charlotte Ikels, and to my Chinese friends determined to help a foreigner understand

Contents

Preface: In Search of Deng

In the summer of 2000, relaxing after a leisurely outdoor supper on Cheju Island, South Korea, I told my friend Don Oberdorfer, one of America's greatest twentieth-century reporters on East Asia, that I was retiring from teaching and wanted to write a book to help Americans understand key developments in Asia. Many people said that my 1979 book, Japan as Number One , helped prepare some U.S. leaders in business and government for Japan's rise in the 1980s, which had shocked many in the West. What would best help Americans understand coming developments in Asia at the start of the twenty-first century? Without hesitation, Don, who had covered Asia for half a century, said, You should write about Deng Xiaoping. After some weeks of reflection, I decided he was right. The biggest issue in Asia was China, and the man who most influenced China's modern trajectory is Deng Xiaoping. Moreover, a rich analysis of Deng's life and career could illuminate the underlying forces that have shaped recent social and economic developments in China.

Writing about Deng Xiaoping would not be easy. When carrying on underground activities in Paris and Shanghai in the 1920s, Deng had learned to rely entirely on his memoryhe left no notes behind. During the Cultural Revolution, critics trying to compile a record of his errors found no paper trail. Speeches prepared for formal meetings were written by assistants and recorded, but most other talks or meetings required no notes, for Deng could give a well-organized lecture for an hour or more drawing only on his memory. In addition, like other high-level party leaders, Deng strictly observed party discipline. Even when exiled with his wife and some of his children to Jiangxi during the Cultural Revolution, he never talked with them about high-level party business, even though they were also party members.

Deng criticized autobiographies in which authors lavished praise on themselves. He chose not to write an autobiography and insisted that any evaluation of him by others should not be too exaggerated or too high. In fact, Deng rarely reminisced in public about past experiences. He was known for not talking very much (bu ai shuohua) and for being discreet about what he said. Writing about Deng and his era thus poses more than the usual challenges in studying a national leader.

I regret that I never had the chance to meet and talk with Deng personally. When I first went to Beijing in May 1973, as part of a delegation sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences, we met Zhou Enlai and other high officials, but we did not meet Deng. One of my strongest impressions from the trip was the buzz in high circles about the recent return of Deng to Beijing from his exile during the Cultural Revolution and the high expectation that he would play some important role that would bring great changes. What role? What changes? We Westerners speculated, but none of us could have predicted the sea change in China that was to occur over the next two decades, and how much China's future would be advanced by the efforts of this singular leader.

The closest I ever came to Deng was a few feet away at a reception at the National Gallery in Washington in January 1979. The reception was a grand gathering of American China specialists from government, academia, the media, and the business world to celebrate the formal establishment of U.S.-China relations. Many of us at the reception had known each other for years. We had often met in Hong Kongthe great gathering spot for China watchers when China was closed to most Westernerswhere we would share the latest news or rumors in our efforts to penetrate the bamboo curtain. It had been a long time since some of us had last seen each other, however, and we were eager to catch up. Further, the National Gallery, where the reception was held, was not meant for speeches: the acoustics were terrible. Unable to hear a thing that Deng and his interpreter were saying through the loudspeaker, we, the gathered throng, continued talking with our fellow China-watcher friends. Those close to Deng said he was upset about the noisy, inattentive crowd, but most of us watching were impressed with how he read his speech as if delivering it to a disciplined Chinese audience sitting in reverential silence.

I have therefore come to know about Deng as a historian knows his subject, by poring over the written word. And there are many accounts of various parts of Deng's life. Despite Deng's admonitions to writers not to lavish praise, the tradition of writing an official or semi-official history to glorify one hero and downplay the role of others remains alive and well in China. Since other officials have been glorified by their secretaries or family members, the careful reader can compare these different accounts. And among party historians, there are some who have, out of a professional sense of responsibility, written about events as they actually occurred.

There will be more books about Deng written in the years ahead as additional party archives become available to the public. But I believe there will never be a better time than now for a scholar to study Deng. Many of the basic chronologies have now been compiled and released, many reminiscences have been published, and I have had an opportunity that will not be available to later historians: I met and spoke with Deng's family members, colleagues, and family members of these colleagues, who gave me insights and details not necessarily found in the written records. In all, I spent roughly twelve months in China (over several years), interviewing in Chinese those who had knowledge about Deng and his era.

The single most basic resource for studying the objective record of Deng's activities is Deng Xiaoping nianpu (A Chronology of Deng Xiaoping). The first publication, a two-volume, 1,383-page official summary of Deng's almost-daily meetings from 1975 until his death in 1997, was released in 2004; the second, a three-volume, 2,079-page description of his life from 1904 to 1974, was published in 2009. The teams of party historians who worked on these volumes had access to many party archives and were conscientious in reporting accurately. The chronology does not provide explanations, does not criticize or praise Deng, does not speculate, does not mention some of the most sensitive topics, and does not refer to political rivalries. Yet it is very helpful for determining whom Deng saw and when and, in many cases, what they talked about.

Many of Deng's major speeches have been compiled, edited, and published in the official Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping. The three-volume work provides a useful account of many of his major policies, although it is critical to interpret them in the context of national and world events at the time. Chronologies about and key speeches and writings by Chen Yun, Ye Jianying, Zhou Enlai, and others are similarly useful.