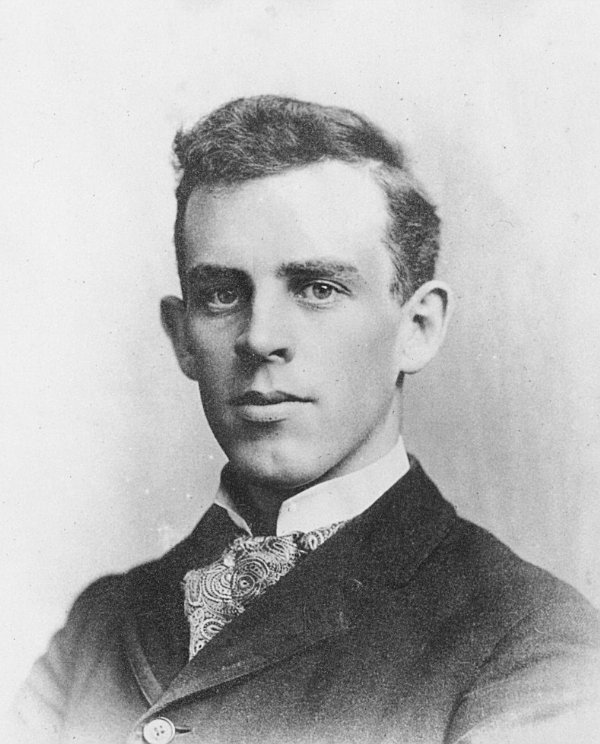

David Fairchild

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2018 by Daniel Stone

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTON and the D colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

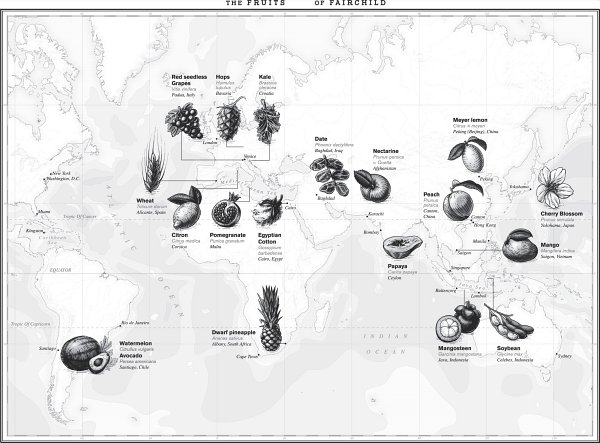

Map and illustrations by Matthew Twombly.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data

Names: Stone, Daniel (Daniel Evan), 1985 author.

Title: The food explorer : the true adventures of the globe-trotting botanist who transformed what America eats / Daniel Stone.

Description: New York, New York : Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Random House, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017030324| ISBN 9781101990582 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781101990605 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Fairchild, David, 18691954Biography. | BotanistsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC QK31.F2 .S76 2018 | DDC 580.92dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030324

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

Version_1

For Walter, my lifes Lathrop

Never to have seen anything but the temperate zone is to have lived on the fringe of the world. Between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Tropic of Cancer live the majority of all the plant species, the vast majority of the insects, most of the strange and dangerous and exciting quadrupeds, all of the great and most of the poisonous snakes and large lizards, most of the brilliantly colored sea fishes, and the strangest and most gorgeously plumaged of the birds. Not to struggle and economize and somehow see the tropics puts you, in my opinion, in the class with the boys who could never scrape together enough pennies to go to the circus. They never wanted to badly enough, thats all.

David Fairchild

The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add [a] useful plant to [its] culture.

Thomas Jefferson

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

One of the humbling parts of being an American is the regular reminder that no matter how swollen Americas pride or power, nothing has been American for very long. A few years ago, it occurred to me that the same way immigrants came to our soil, so did our food.

I was at my desk one morning researching a story for National Geographic when I came across a map showing where popular crops were first domesticated. Floridas famous oranges grew first in China. The bananas in every American supermarket originated in Papua New Guinea. Apples that Washington claims as its heritage came from Kazakhstan, and Napas grapes saw their first light in the Caucasus. To ask when these became American crops seemed a little like asking how people from England became Americans. It was, in a word, complicated.

But as I continued to dig, deeper and deeper, there appeared to be a moment of clarity, a moment in history when new foods arrived on Americas shores with the suddenness of a steamship entering a harbor. The late nineteenth centurya time known as the Gilded Age, the rise of industrial America, the golden age of travelwas a formative era in the United States. The opening of oceans and countries allowed a young scientist named David Fairchild to scour the planet for new foods and plants and bring them back to enliven his country. Fairchild saw world-changing innovation, and in a time that glorified men of science and class, he found his way into parlors of distinction not by pedigree but through relentless curiosity.

The way I became obsessed with this story seems, in retrospect, predictable. All my life Ive been fascinated by fruit, the more tropical the better. When I was a kid, my parents took my sister and me to Hawaii because my dad thought we needed to see things. I ate two whole pineapples, followed by a stomachache that burned hotter than Mauna Loa. Sometimes at home my mom would cut me a mango by shaving down the sides, and while I ate the pieces, shed keep whittling away at the stone. It was mangoes, not my dentist, that taught me the value of floss.

In college, I worked on a farm, walking the hot rows of an orchard grading peaches. The goal was to find the superior varieties to prioritize for the following season, like performing eugenics on fruit. But distraction came easy. Id finish shifts with the juice of dozens of peaches soaking my shirt, and, again, usually a stomachache. Before I moved to Washington, D.C., to write about politics, a friend offered me a job on his farm, picking fruit and selling it at the kind of Northern California farmers markets where people use words like varietals and terroir. I declined so I could follow a dream, although I spent years sitting in congressional hearings imagining my alter ego, windows down in a pickup truck, on empty farm back roads.

Several years later, when I heard about Fairchild, what struck me first was that this was a man who had made fruit his joband not just familiar crops, but things no one had ever tasted. When I told friends how Fairchild had given the United States its first official avocados, people wanted to nominate him for sainthood. I started to enjoy reciting his greatest hitsdates, mangoes, pistachios, Egyptian cotton, wasabi, cherry blossomsand watching peoples eyebrows go up. Almost every time they would say something like, Gosh, it never dawned on me someone brought those things here. We tend to think of food from the ground as a type of environmental entitlement that predates humans, a connection with the raw planet itself. But what we eat is no less curated than a museum exhibit. Fairchild saw the opportunity in a bare canvas to add new color and texture.

Fairchilds life is the story of Americas blooming relationship with the world at the turn of the twentieth century. He visited more than fifty countries, almost all by boat, before airplanes and automobiles shrank the planet. His passions and interests preceded our modern-day fixation on food and what the economic, biological, and ecological effects are of a meals cultivation, transport, and consumption. Fairchild was the embodiment of boundless hunger and insatiable wanderlust, and his lifes work was a quest to answer,