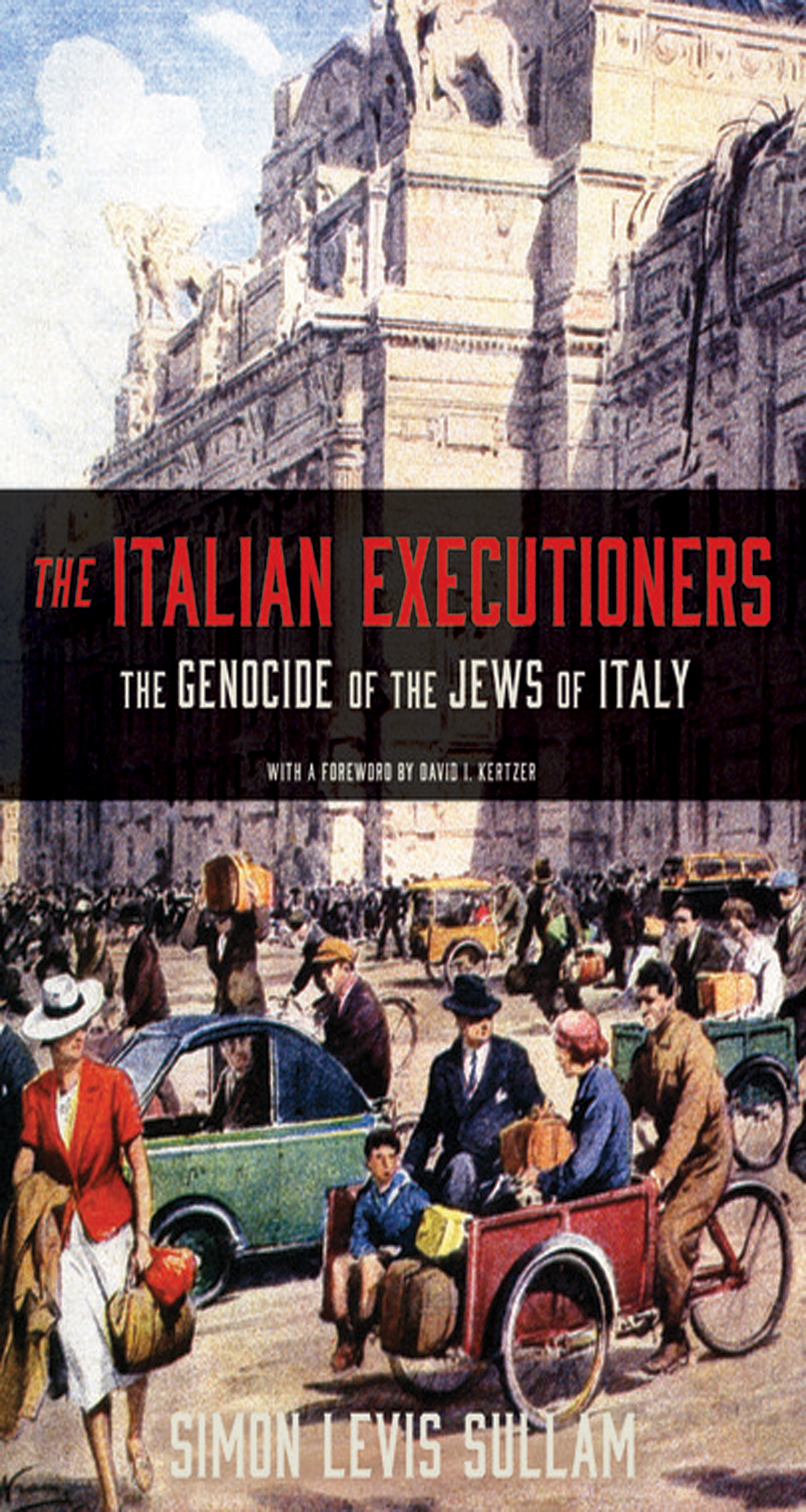

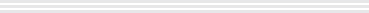

The Italian Executioners

The Italian Executioners

The Genocide of the Jews of Italy

SIMON LEVIS SULLAM

Translated by Oona Smyth with Claudia Patane

With a foreword by David I. Kertzer

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: Milan, Italy, 1943. SeM/Universal Images

Group/Bridgeman Images

All Rights Reserved

First published as I carnefici italiani in January 2015 by

Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore, Milan, Italy. Copyright 2015 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore

ISBN 978-0-691-17905-6

Library of Congress Control Number 2018938054

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Baskerville 120 Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

David I. Kertzer

Foreword

The impulse to erase or recast painful historical memories may well be a universal human trait, but it can be a dangerous one. When the uncomfortable events of the past are replaced in memoryand, even worse, in historiographyby a triumphal account of virtue, the danger is all the greater. It is just such a misrepresentation of the past that Simon Levis Sullam tackles head-on in this short but important book.

Those who have spent much time in Italy in recent years may be pardoned if they get the impression that Italians fought in World War II not on the side of the Nazis but with the Americans and British against the Nazis. From the immediate postwar years to the present, memories of the relations between the Italians and the Nazis have focused for the most part on the Resistance. One small indication of this: Italy boasts dozens of centers for the study of the Resistance but few for the study of Fascism. Yet the Resistance lasted a year and a half and involved only limited parts of the country and a small minority of Italians. By contrast, the Fascist regime lasted two decades, covered the whole country, and involved millions.

If Italians are, understandably perhaps, eager to mis-remember their past support for the Fascist regime and their past alliance with Nazi Germany, they have shown themselves even more eager to construct a wholly misleading history of their responsibility for the persecution and cold-blooded murder of their fellow Italians whose only sin was being Jewish. It is this history that Levis Sullam seeks to set straight in these pages.

In the widespread attempts to separate Italians from any responsibility for the Holocaust, few elements have been more central than ignoring Italys vicious campaign of persecution of its Jewish citizens that was launched in 1938 with the introduction of the draconian racial laws. Adults were thrown out of their jobs, their children were thrown out of the schools, and all Jews were cast as nefarious enemies of good, Christian Italians. As their Jewish neighbors were persecuted, it was the rare non-Jewish Italian who spoke up for them. More commonly, former friends crossed the street to avoid having to greet them. Italian academics showed themselves all too eager to benefit from the openings created when their Jewish colleagues were cast out and, indeed, following the war, fought mightily to resist giving their positions back to them.

Italys antisemitic campaign, beginning two years before Italy entered the war, can properly be placed alongside the antisemitic campaign in these years in Germany (and elsewhere in central Europe) as a crucial step in the process that would make the Holocaust possible. Before people could entertain the idea of sending Jewish children and other defenseless Jews to their death, simply for being Jewish, they first had to rob them of their humanity, to cast them as dangerous enemies. This the Italians did with the imposition of the racial laws.

The antisemitic campaign facilitated the mass murder of Italys Jews in another way as well, as Levis Sullam shows, for it created both a census of all of the Jews and a bureaucracy devoted to their surveillance and persecution. As he notes in these pages, the roundup of Frances Jews was slowed by the lack of documentation on who the Jews were and where they lived. The Italians had no such problem, thanks to the racial laws and the antisemitic government machinery that had been in place for five years before the roundups began.

An important part of Italians ability to distance themselves from this past has been the creation of the myth of the good Italian. Levis Sullam shows that this myth was constructed very early, beginning in the final months of the war, as Italians quickly remade their identities to cast themselves on the side of the wars victors. In this convenient narrative, Italians had only positive feelings for their Jewish fellow citizens. All of the horrible things done to the Jews were the work of the evil Germans, notwithstanding the Italians own heroic efforts to protect them.

Insofar as the Holocaust is concerned, this myth relies both on the erasure of the five years of the Italian state campaign against the Jews in the years leading up to the Shoah and on the misrepresentation of how it was that those thousands of Jews in Italy in 194345 came to be identified, located, and transported to the death camps.

The Roman Catholic Church has been among the institutions with the greatest stake in this historical misrepresentation. In the Holy Sees official version of this history, contained in the 1998 Vatican statement We Remember, the antisemitism that led to the Holocaust was wholly distinct from the religious anti-Judaism that the Church had promulgated. As Levis Sullam shows, while this is a comforting account, it bears no relation to the actual history of the demonization of the Jews that was employed to justify their mass murder. The case Levis Sullam offers of a prominent Venetian physician who whipped up public sentiment against the Jewish threat is emblematic. His published screeds blended pseudoscience with classic Christian warnings of the terrible divine punishment that awaited the Jews, who had continued to remain distant from Christ. Likewise, the most important Fascist state vehicle for spreading hatred of Italys Jews, the twice-a-month illustrated publication La difesa della razza, was filled with traditional Christian tropes demonizing the Jews, from well poisoning to ritual murder.

Levis Sullam is able to draw on a number of important recent studies, along with published first-person testimonies, to show the crucial role Italians played in the roundup of Jews beginning in the fall of 1943. Of all the Jews sent to their death from Italy, half were seized not by German soldiers but by Italians. Moreover, in those cases where it was German soldiers who took them, the Germans relied on Italians to help them locate the Jews in their midst. In such cases, Italians often accompanied the Germans for this purpose.

Next page