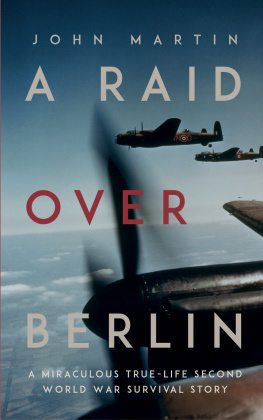

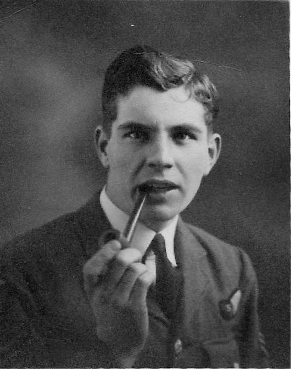

London-born John Martin volunteered for the RAF as a trainee wireless operator in 1941, aged nineteen.

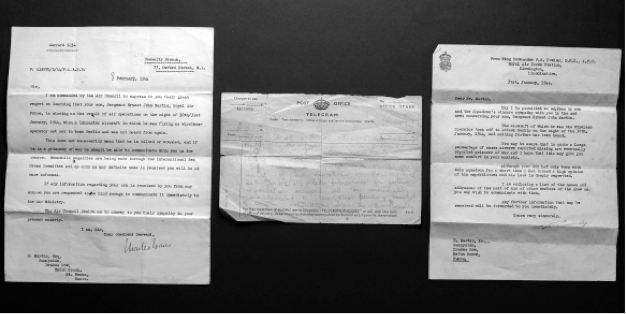

On completing his training, he was posted to RAF Kermington, in Lincolnshire. Here he crewed Lancaster bombers until, on the night of January 30th, 1944, on only his third operational mission, his plane was brought down over Germany. After a miraculous escape, his parachute opening in the chaos of a disintegrating aeroplane, he was captured and interrogated before being held as a prisoner of war.

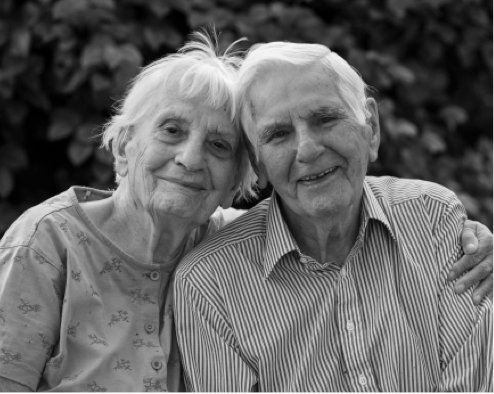

After the Allies finally crushed the Nazi regime in the spring of 1945, bringing the war in Europe to an end, John Martin was liberated by British troops and repatriated back to life in Britain. He returned home to his family and was met by his fiance, Adelaide, who he married shortly after. The couple went on to raise a family. John Martin, now aged ninety-six, lives in Cardigan, Wales.

Chapter 6

On the move

The evacuation of Stalag Luft VI was carried out, in July 1944, with no signs of panic from our captors; it was a hasty withdrawal but well organised. It wasnt until very early in the morning on the next day, after seeing the columns of refugees, that we found that the whole of E Lager, where the Americans were held, had already been moved out.

As this realisation began to sink in armed guards entered our own lager, separating the two rows of huts. By the time I realised what was going on, the occupants of the hut directly opposite, where David was, had already been ousted. I watched as they were moved out, carrying all they could manage in hastily made backpacks, but I could not catch sight of him. They were herded off, much like cattle, except that the drovers were much more plentiful and had bayonets fixed ready to discourage any slow movers. It was not long before all the huts on the opposite side were empty, creating a strange silent atmosphere along the whole row.

It was not until the war in Europe was over that I learned from David, and others who went with him, what a terrifying experience all those on their side of K Lager, along with the whole of the occupants of E Lager, had endured. I soon realised that, not for the first time, I had been blessed by fate through having been allocated a different hut.

Their destination was a prison camp, close to the shores of the Baltic, called Stalag Luft IV, near the town of Gross Tycho in the Province of Pomerania.

From Stalag Luft VI, they were marched to the railway station and loaded into cattle trucks in which they made the short journey to the port of Memel. There they were loaded onto a very decrepit, small merchant ship, the Insterburg, which was normally used for carrying coal in its two holds. After being ordered to leave the packs containing their pathetic possessions on deck, using just one single vertical ladder, they were forced below, into a filthy hold. The weather by now was very warm and the heat, accumulated in the steel hold, was almost unbearable; what they needed desperately was water.

The floor space of each of the two filthy, stinking holds was crammed to absolute capacity with hundreds of men. Those on the sides had great difficulty in maintaining a foothold because of the slope of the hull, and it was only after a lot of shuffling around that room was found for most men to sit with knees drawn up tight, but the heat and the air quality got worse, as did the desperate need for water. Eventually this was provided by lowering just one bucketful down at a time. Those waiting were only able to watch while others drank; this must have been torture.

Although it must have been known that the voyage would take sixty hours, no provision had been made for sanitation. Only a few of the hundreds that had been packed into the holds had been allowed back on deck after the ship set sail to relieve themselves; the rest were expected to make do with a bucket. This was raised up and down by a chain just as the water had been; some said the same bucket was used for both purposes. True or not, a bucket soon proved inadequate for this purpose and a bit of the precious floor space in the hold had to be given over to human waste. With practically no ventilation, the resultant stench increased the misery below.

To add even more terror, it was known to some of the RAF prisoners aboard that mine laying operations were frequently carried out in this area of the Baltic Sea, as a result every bang on the side of the ship when it collided with flotsam caused them to cringe, waiting for an explosion. Another thing that caused great concern to the few who had been allowed back on deck after setting sail, was that they could see that an E boat was following them. Were the German crew of their ship to be taken off at some point, leaving all the prisoners helpless when it was sunk by a torpedo?

__WRAF.jpg)