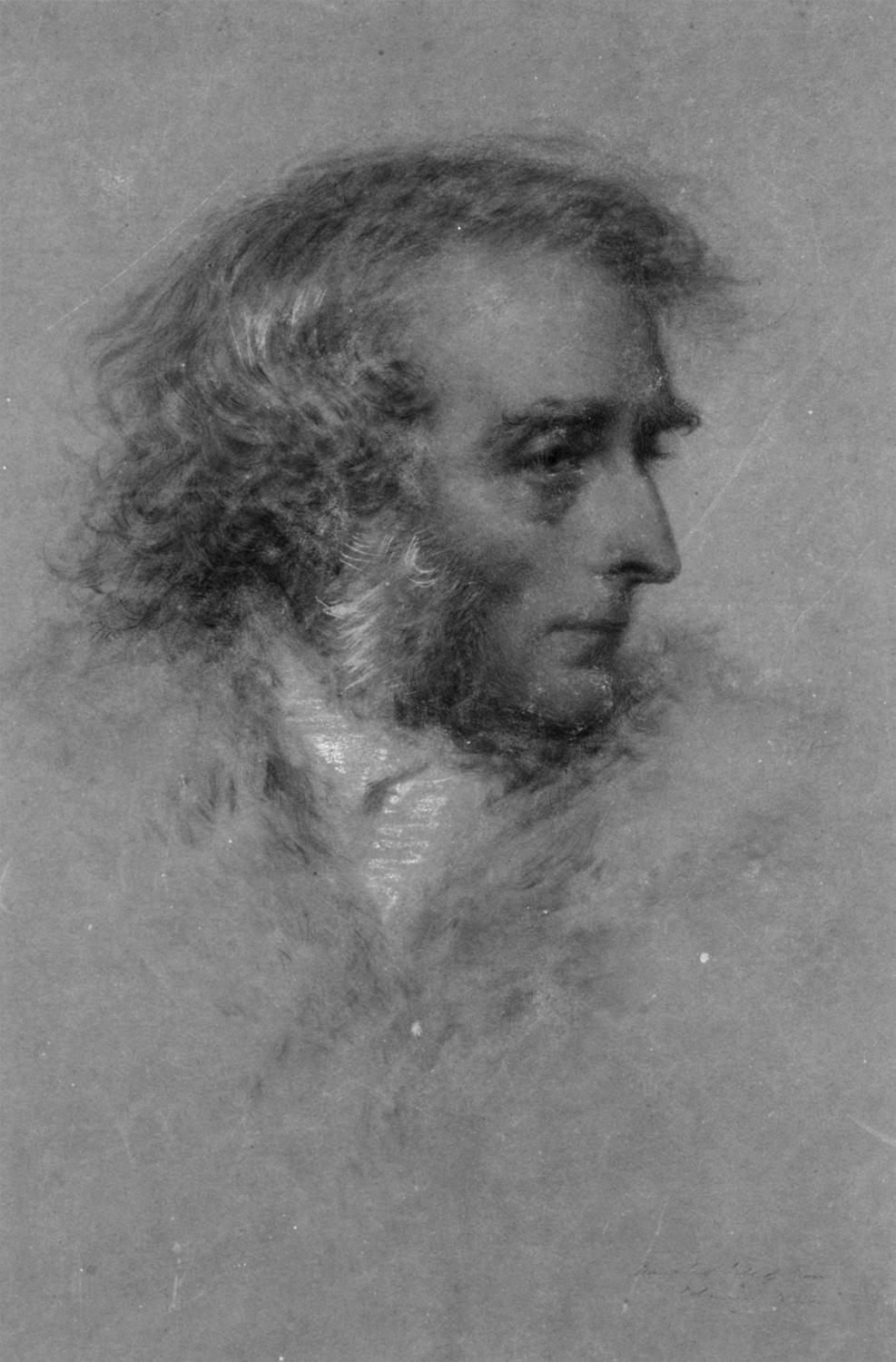

Martin Myrone

During February and March 1849, the popular weekly newspaper the IllustratedLondonNews featured a series of reports on the newly opened exhibition of contemporary art at the British Institution in Pall Mall, in central London. Aimed at respectable, middle-class, family orientated readers around the country, the IllustratedLondonNews commented on and illustrated exhibitions and public displays in the context of its very broad coverage of domestic and international news, culture, sport and society gossip. Dwelling on this picture, the reviewer ventured a biographical notice of the painter, the inaccuracies of which prompted Martin to write to the editor, John Timbs (18011875), offering his own autobiographical notes and hoping to set the record straight. Published in the next issue (17 March), this is the fullest statement about his life made by the artist, giving an exceptional insight into the artists self-perception and public persona. It is this letter, much-quoted in later accounts as the artists autobiography, which is reprinted here, together with materials from the offending review.

The review, containing some errors of fact regarding Martins early life and its limited praise for the artists latest production, is unsigned, and it has been proposed that the author was the prolific writer Peter Cunningham (18161869). As he had married the painters second daughter, Zenobia, in 1842, and was therefore Martins son-in-law, we would expect that he might have been better informed. But this later letter is longer, fuller, and is obviously able to cover more of his life (even though Martin apparently simply runs out of space and feels compelled to compress his account of the last twenty years).

Coming from a humble background in Northumbria, and training not as a fine artist but as a decorative painter, Martin struggled to become integrated into the metropolitan art world when he moved to London in 1806. Forced to make a living working as a china-painter and drawing master, he was led to produce paintings whose novelty and sensational effects would secure the publics attention, even if he lacked reputation and connections in the art world. Although he achieved unprecedented public acclaim for the large paintings of biblical catastrophe and natural disaster that he exhibited in the late 1810s and 1820s, much of the art establishment and the majority of serious-minded critics remained at best sceptical about, and sometimes openly hostile towards, his art. He was never elected a member of the Royal Academy of Arts, Londons leading art institution, as might have been expected of any artist of his public prominence. Martin was, in the fullest sense of the term, a commercial artist, whose images were geared towards a mass audience for art, and who needed to make money from his paintings and prints. Martins dedication to printmaking, and his execution of repetitions of key compositions, suggest his interest in making the most of his original inventions. And whilst the Royal Academy had a rule against artists showing the same composition at its exhibitions more than once, Martin often used alternative exhibition spaces (notably that of the British Institution) to reshow works. His efforts at maximising his artistic investments were, however, frequently undermined by piracy, plagiarism, and commercial exploitation, which made him acutely conscious of his public image and the need to manage his reputation. He was aware, too, of how his art was constantly compared to works by other painters who had a more conventional painting style, and more official recognition, and how he was perceived by many contemporary commentators as being overlooked by, and perhaps in return antagonistic towards, the art establishment. For example, Francis Danby (17931861), who in the 1820s had successfully established himself as a painter of sublime landscapes to rival Martin, had been an Associate of the Royal Academy since 1825. In 1849 he exhibited a large and atmospheric picture at the British Institution that was paired by the critics with Martins Joshua. The painter William Bell Scott (181190) recalled that Danby had perhaps the actual advantage of a more skilful command of the palette, and he had the accidental advantage of being taken up, in opposition to Martin, by the Academy.

1

JoshuaCommandingtheSuntoStandStilluponGibeon 1848

Oil on canvas 148 246 cm

Huddersfield Art Gallery, Kirklees Collection (Dewsbury Town Hall), Kirklees Council

a recovery of sorts when he returned to painting, using a project in 18389 to paint Queen Victorias coronation to make contact with potential patrons (in which effort he had some success). But although he exhibited and indeed sold several major canvases in the 1840s, he was more often to exhibit modest landscapes and watercolours at the London exhibitions. Accordingly, his critical reputation remained by 1849 fragile, his financial circumstances unstable.

If Martin was sensitive about his monetary situation and his perceived exclusion from the art establishment, the IllustratedLondonNews article was destined to cause offence. With a degree of romantic exaggeration that its subject found unacceptable, the biography outlines the artists humble background in the north of England, his artisanal training, his precarious existence in London, and the series of popular pictures he showed at exhibition in the later 1810s and 1820s. The report goes to some length to argue that Martin sold himself short in the following years, as he failed to capitalise on this initial success and exhibited a series of substandard works. Thus is explained Martins failure to be elected as a member of the Royal Academy, with the implication that he displayed some degree of haughtiness. In response, Martin was at pains to point out that his disagreement was not with individual members but rather the monopolistic basis of the Academy as an institution.

But there was more at stake than professional manners. For the writer in the IllustratedLondonNews, as for other reviewers of the time, Joshua represented something of a return to form for Martin. It was, unusually, a second full-scale version of a picture that had first been seen by London exhibition-goers more than thirty years earlier. The original Joshua was a surprise hit at the annual exhibition of the Royal Academy in London 1816, helping to establish Martins name as a painter of a novel form of historical and sublime landscapes. As Martin notes, he was awarded a cash prize by the British Institution when it was exhibited there the following year, but its later history was more troubling to the painter. In 1821, Martin secured even greater public acclaim when his BelshazzarsFeast was shown at the British Institution. While the picture was on show, Martin sold it and Joshua to his former employer, the glass-painter William Collins Although the injunction does not seem to have been imposed as Martin produced his print, the fact that Collins was able to claim his commercial rights over an image originated by the painter was a source of aggravation. The issue of an artists right to exploit commercially his own productions exercised Martin throughout his career, something that he alludes to in his autobiography when he refers to the imperfect laws of copyright leading to my property being so constantly and variously infringed.