.

Starting now the hours of the clock

Will hang on a hair around my neck

Starting now the stars will stop

In their courses sun cock-crow shadows

And everything that time proclaimed

Is now dead and dumb and blind

For me all nature is silenced

With the ticking of the law and its measure .

Friedrich Nietzsche

he flowing river of time, carrying us from inception to eternity, is both invention and illusion; a phantom child of mortal dreams and fears. So the scientists tell us. They assure us that velocity can stretch time like wool spun on a distaff, and that relativity makes time merely another variable in a host of equations whirling around the universe.

he flowing river of time, carrying us from inception to eternity, is both invention and illusion; a phantom child of mortal dreams and fears. So the scientists tell us. They assure us that velocity can stretch time like wool spun on a distaff, and that relativity makes time merely another variable in a host of equations whirling around the universe.

Certainly our time, Western time, the spliced and segregated seconds, minutes, and hours by which we regulate our busy lives, was an invention of the late Middle Ages. Before then, time was measured naturally, and by those things of which it was made: the sun, the moon, and the stars; revolving watches of sleepy soldiers; human criers at dawn and cattle lowing in the gloaming; burning tapers during peace and burning cities during war; national disasters and signal triumphs; the reigns of kings, the death of princes, the fall of empires; comets and their strikes, freakish births, sudden miracles, and the rumor of dragons; heavy rains, sweeping plagues, hard winters, and sudden springs; and, of course, by church bells tolling, cocks crowing, and sand bleeding through the hourglass.

In ancient days, the world itself served as a vast clock. People closely watched the seasons change: winter thawed into spring, which warmed into summer; summer surrendered to cool autumn, until the first freeze of winter descended and the cycle began again.

The heavens kept time with the earth. The sun dependably marked off the days hours as it journeyed westward across the sky: one circuit of the sun from dawn to dawn is, in fact, the very definition of a day The sun also acted like any sensible person, retreating from winters cold and returning with the warming days of spring.

After sunset, in any season, the lambent moon rose to guide travelers through the night. The moon also, mysteriously but conveniently changed its shape, growing from thin crescent to full orb and shrinking back to crescent again in a cycle that took about twenty-nine days. The inconstant moon proved a reliable measure for longer stretches of time, from new moon to new moon. The ancient Germans called this period of about thirty days a monath, and, but for a sliding vowel, so do we still.

From the most ancient times, people recognized that the earthly and celestial turning points of the year were linked. The suns travels delineated the seasons. The solstices, when the sun reached its farthest northern and southern position in the sky inaugurated summer and winter; the equinoxes, when the sun stood midway between the solstices and the length of day and night were equal, marked the advent of spring and autumn.

The gauzy night sky held other signposts. Certain stars appeared annually, like heralds announcing the seasons. Throughout the Western world, the great hourglass-shaped constellation of Orion warned of impending winter, while Leo the lions right triangle marked a sure sign of spring. The Pleiades, so diaphanously lovely that to really see them one had to look the other way, led summer into fall.

All nature obeyed the dictates of cyclical time, not least human beings. Just as the sun waned from blazing summer strength to a feeble spark on the far horizon, so too did the young eventually grow old; just as the trees in the forests and the crops in the fields withered with the onset of fall, so too did human beings age, sicken, and die. Nature yearly reiterated the life cycle of humankind, and each individuals fate reflected the dance of the cosmos.

These cycles of time, and the mysterious connection between people and their surrounding universe, were codified in sacred festivals, temporal maps charting out the course of the year as mariners charted voyages. The great festivals of the year, held at the solstices, equinoxes, and important agricultural turning points, ritualized this connection between the cycles of human life and those of the natural world.

Festivals marked out the progress of the year. They celebrated the return of the sun after the winter solstice, marked springs first planting under favorable stars, called revelers to delight in the flowering May, and solemnly observed the final whispering night of autumn. They also loaned the power of ritual to lifes simple necessities: ripening crops, the birth of new flocks, ice breaking on a river, the day the rains came. These simple events took on a patina of sanctity, of destiny, in a world still ruled by neighborhood gods.

Although life was shorter, time was longer, moving with the steady but unhurried sun from one season to the next, changing in increments with the moon, wheeling with the great circle of the stars.

Then, around 1350, carefully stowed beneath the decks of trading ships, keeping company with gunpowder and the astrolabe, the first mechanical clocks arrived in Europe. Modern time made its debut, and changed its creators.

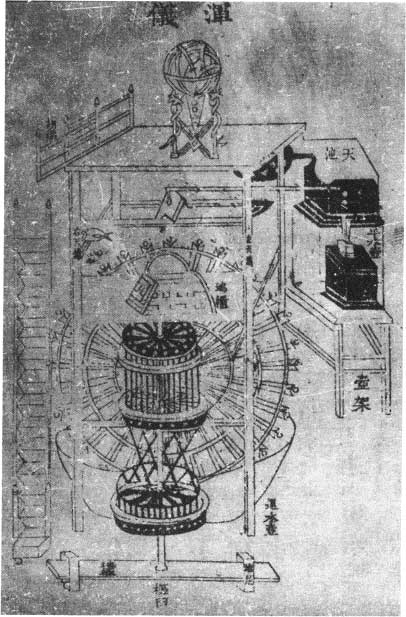

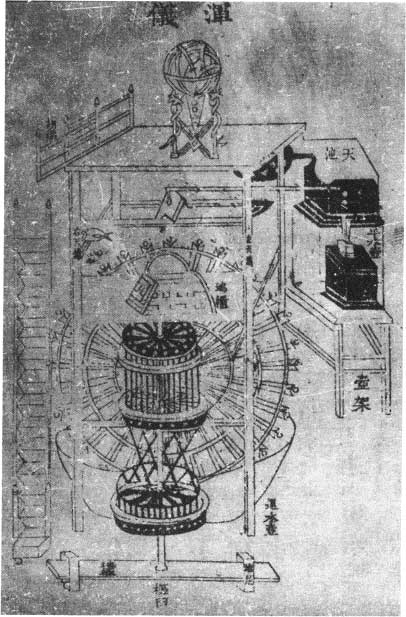

Design for a Chinese water clock, A.D. 1008

Modeled on the ancient Chinese water tower, early clocks used falling drops of water to count out the seconds and minutes of the day. For fourteenth-century observers, accustomed to marking the hours by the shouts of town criers and the tolling of church bells, the first clocks must have been startling reminders of humanitys bondage to time, counting out the seconds as misers counted coins. Moreover, with an ear bent toward the new machine, one could literally hear time fall; one drop of water after the other stealing the seconds away.

he flowing river of time, carrying us from inception to eternity, is both invention and illusion; a phantom child of mortal dreams and fears. So the scientists tell us. They assure us that velocity can stretch time like wool spun on a distaff, and that relativity makes time merely another variable in a host of equations whirling around the universe.

he flowing river of time, carrying us from inception to eternity, is both invention and illusion; a phantom child of mortal dreams and fears. So the scientists tell us. They assure us that velocity can stretch time like wool spun on a distaff, and that relativity makes time merely another variable in a host of equations whirling around the universe.