The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

The only problem is

they dont think much

about us

in America.

Alfrredo Navarro Salanga, Manila

December 7, 1941. Japanese planes appear over a naval base on Oahu. They drop aerial torpedoes, which dive underwater, wending their way toward their targets. Four strike the USS Arizona, and the massive battleship heaves in the water. Steel, timber, diesel oil, and body parts fly through the air. The flaming Arizona tilts into the ocean, its crew diving into the oil-covered waters. For a country at peace, this is a violent awakening. It is, for the United States, the start of the Second World War.

There arent many historical episodes more firmly lodged in national memory than this one, the attack on Pearl Harbor. Its one of the few events that most people can put a date to (December 7, the date which will live in infamy, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt put it). Hundreds of books have been written about itthe Library of Congress holds more than 350. And Hollywood has made movies, from the critically acclaimed From Here to Eternity (1953) starring Burt Lancaster to the critically derided Pearl Harbor (2001) starring Ben Affleck.

But what those films dont show is what happened next. Nine hours after Japan attacked the territory of Hawaii, another set of Japanese planes came into view over another U.S. territory, the Philippines. As at Pearl Harbor, they dropped their bombs, hitting several air bases, to devastating effect.

The armys official history of the war judges the Philippine bombing to have been just as disastrous as the Hawaiian one. At Pearl Harbor, the Japanese hobbled the United States Pacific fleet, sinking four battleships and damaging four others. In the Philippines, the attackers laid waste to the largest concentration of U.S. warplanes outside North Americathe foundation of the Allies Pacific air defense.

The United States lost more than planes. The attack on Pearl Harbor was just that, an attack. Japans bombers struck, retreated, and never returned. Not so in the Philippines. There, the initial air raids were followed by more raids, then by invasion and conquest. Sixteen million FilipinosU.S. nationals who saluted the Stars and Stripes and looked to FDR as their commander in chieffell under a foreign power. They had a very different war than the inhabitants of Hawaii did.

Nor did it stop there. The event familiarly known as Pearl Harbor was in fact an all-out lightning strike on U.S. and British holdings throughout the Pacific. On a single day, the Japanese attacked the U.S. territories of Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, Midway Island, and Wake Island. They also attacked the British colonies of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, and they invaded Thailand.

It was a phenomenal success. Japan never conquered Hawaii, but within months Guam, the Philippines, Wake, Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong all fell under its flag. Japan even seized the westernmost tip of Alaska, which it held for more than a year.

Looking at the big picture, you start to wonder if Pearl Harborthe name of one of the few targets Japan didnt invadeis really the best shorthand for the events of that fateful day.

Pearl Harbor wasnt how people referred to the bombings, at least not at first. How to describe them, in fact, was far from clear. Should the focus be on Hawaii, the closest target to North America and the first bit of U.S. soil Japan had struck? Or should it be the Philippines, the far larger and more vulnerable territory? Or Guam, the one that surrendered nearly immediately? Or all the Pacific holdings, including the uninhabited Wake and Midway, together?

The facts of yesterday and today speak for themselves, Roosevelt said in his address to Congresshis Infamy speech. But did they? JAPS BOMB MANILA, HAWAII was the headline of a New Mexico paper; JAPANESE PLANES BOMB HONOLULU, ISLAND OF GUAM was that of one in South Carolina. Sumner Welles, FDRs undersecretary of state, described the event as an attack upon Hawaii and upon the Philippines. Eleanor Roosevelt used a similar formulation in her radio address on the night of December 7, when she spoke of Japan bombing our citizens in Hawaii and the Philippines.

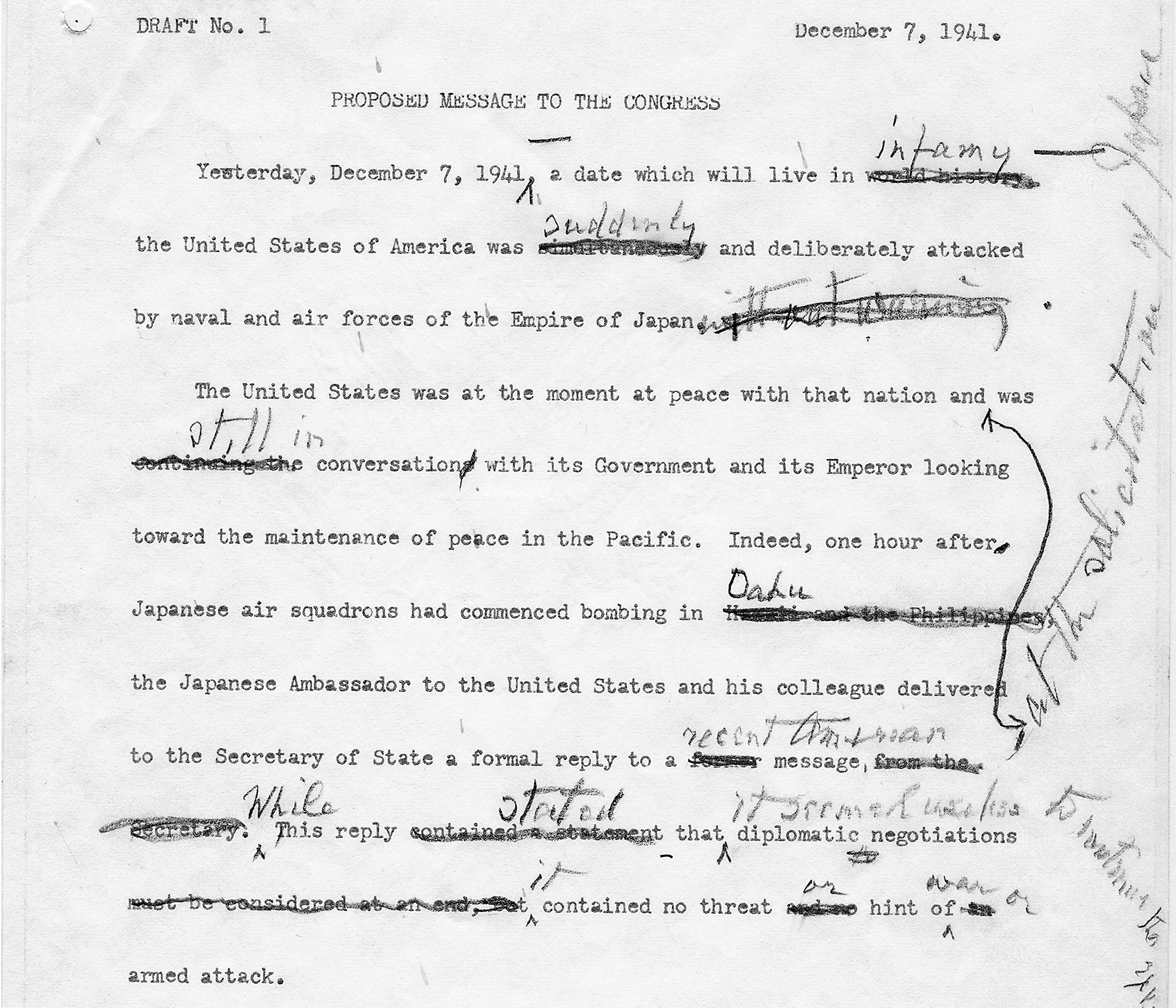

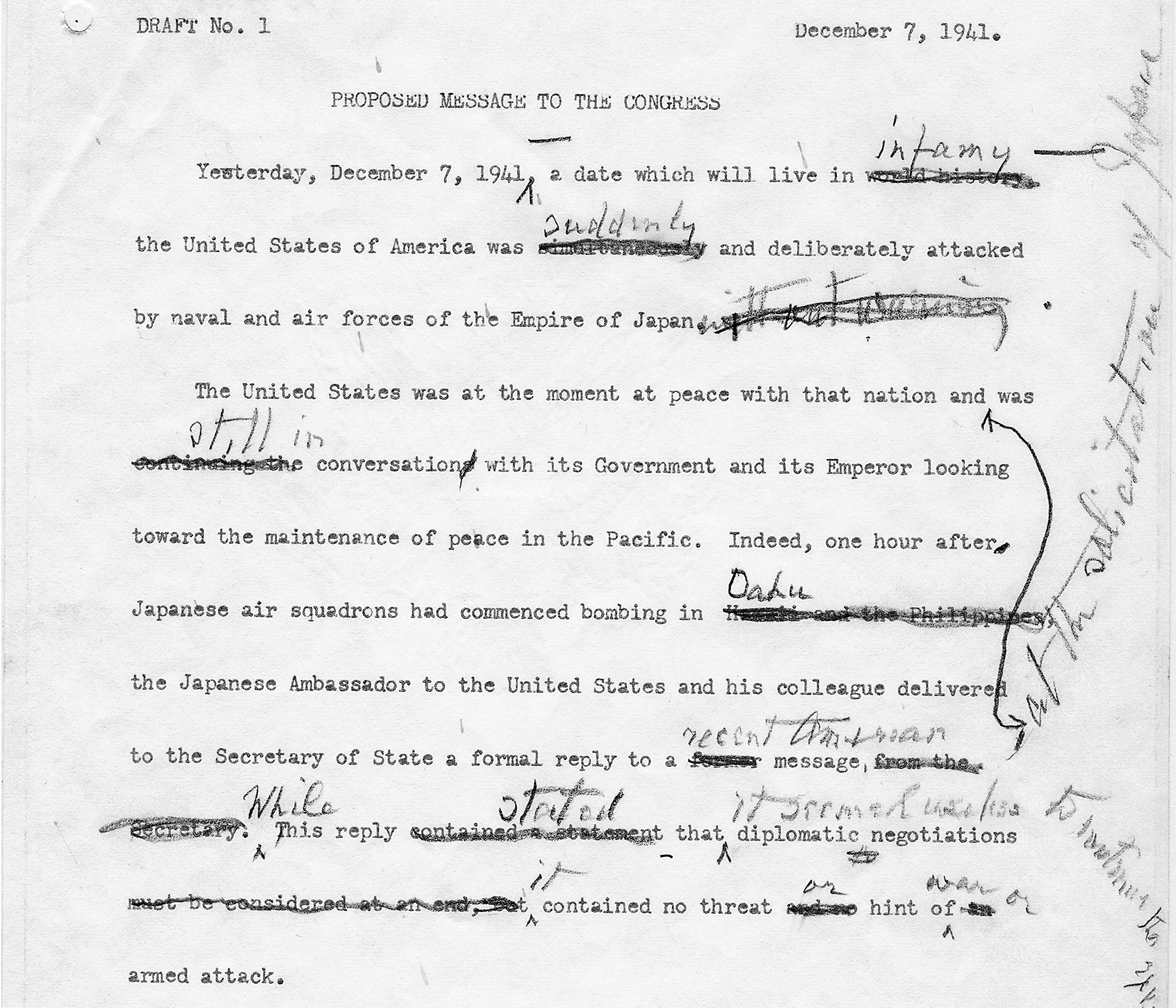

That was how the first draft of FDRs speech went, too. It presented the event as a bombing in Hawaii and the Philippines. Yet Roosevelt toyed with that draft all day, adding things in pencil, crossing other bits out. At some point he deleted the prominent references to the Philippines and settled on a different description. The attack was, in his revised version, a bombing in Oahu or, later in the speech, on the Hawaiian Islands. He still mentioned the Philippines, but only as an item on a terse list of Japans other targets: Malaya, Hong Kong, Guam, the Philippines, Wake Island, and Midwaypresented in that order. That list mingled U.S. and British territories together, giving no hint as to which was which.

Roosevelts December 7 draft of the Infamy speech. Squadrons had commenced bombing in Hawaii and the Philippines on the seventh line has been changed to squadrons had commenced bombing in Oahu.

Why did Roosevelt demote the Philippines? We dont know, but its not hard to guess. Roosevelt was trying to tell a clear story: Japan had attacked the United States. But he faced a problem. Were Japans targets considered the United States? Legally, yes, they were indisputably U.S. territory. But would the public see them that way? What if Roosevelts audience didnt care that Japan had attacked the Philippines or Guam? Polls taken slightly before the attack show that few in the continental United States supported a military defense of those remote territories.

Consider how similar events played out more recently. On August 7, 1998, al-Qaeda launched simultaneous attacks on U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Hundreds died (mostly Africans), and thousands were wounded. But though those embassies were outposts of the United States, there was little public sense that the country itself had been harmed. It would take another set of simultaneous attacks three years later, on New York City and Washington, D.C., to provoke an all-out war.

An embassy is different from a territory, of course. Yet a similar logic held in 1941. Roosevelt no doubt noted that the Philippines and Guam, though technically part of the United States, seemed foreign to many. Hawaii, by contrast, was more plausibly American. Though it was a territory rather than a state, it was closer to North America and significantly whiter than the others. As a result, there was talk of eventual statehood (whereas the Philippines was provisionally on track for independence).

Yet even when it came to Hawaii, Roosevelt felt a need to massage the point. Though the territory had a substantial white population, nearly three-quarters of its inhabitants were Asians or Pacific Islanders. Roosevelt clearly worried that his audience might regard Hawaii as foreign. So on the morning of his speech, he made another edit. He changed it so that the Japanese squadrons had bombed not the island of Oahu, but the American island of Oahu. Damage there, Roosevelt continued, had been done to American naval and military forces, and very many American lives had been lost.