..... STRUNG OUT ON ARCHAEOLOGY.....

Strung out on Archaeology

An Introduction to Archaeological Research

.....

Laurie A. Wilkie

With Illustrations by

Alexandra Wilkie Farnsworth

First published 2014 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2014 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilkie, Laurie A., 1968

Strung out on archaeology:an introduction to archaeological research/Laurie A. Wilkie; with illustrations by Alexandra Wilkie Farnsworth.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61132-267-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-61132-269-9 (consumer ebook)

1. ArchaeologyMethodology. 2. Archaeology and history. 3. CarnivalLouisianaNew Orleans. 4. BeadsLouisianaNew Orleans. 5. New Orleans (La.)Antiquites. I. Title. II. Title: Introduction to archaeological research.

CC75.W464 2014

930.1028dc23

2013049058

ISBN 978-1-61132-267-5 paperback

To my daughter Alex:

Lets hope we sell enough of

these to pay for your college education;

if not, its still really flattering to have a book dedicated to you right?

Contents

Preface:

What Is This Book About?

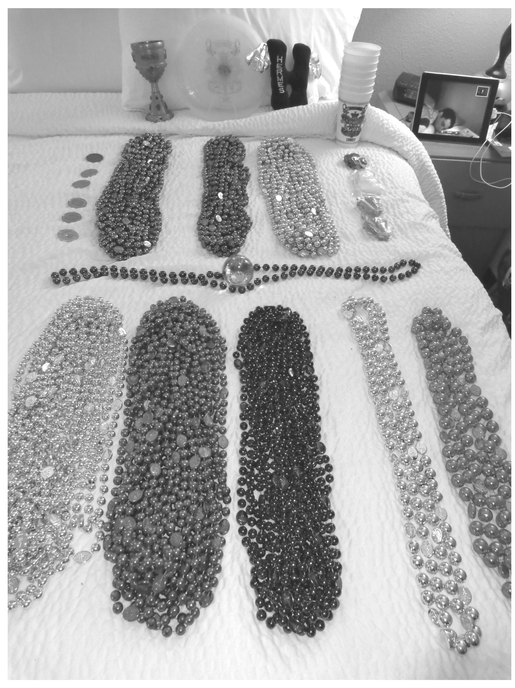

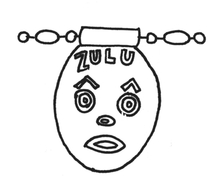

This book is about two of my greatest passions: archaeology and Mardi Gras, and the ways they can inform one another. In the United States, most citizens holding a high school diploma have heard of archaeology and the celebrations of New Orleans Mardi Gras, but are likely to have misconceptions about each. Archaeologists are often conflated with the characters of Indiana Jones, Lara Croft, or some other treasure-hunting adventurer who has been labeled as an archaeologist in popular culture. Likewise, when people hear "Mardi Gras," they are more likely than not to think simply of girls-gone-wild-spring-break-type debauchery without having any sense of the traditions and heritage associated with these centuries-old traditions. A text book revolving around these topics gives me the opportunity to illuminate understandings of one of these topics through the other and vice versa. While this book is primarily an introduction to Archaeology, I will use a contemporary archaeology project focusing on the bead throwing culture of Louisiana Mardi Gras to explain and illustrate archaeological thought and methodology.

You might think, Mardi Gras and Archaeology? Together? That seems like a cynical mash-up imagined by a publisher to sell a less-than-solid introductory textbook, doesn't it? But no, the idea originated with me and for some particular personal and intellectual reasons. To explain why this book exists as it does requires some background information, or what we will later learn the post-processualist archaeologists called historical context".

A few years ago, the New York Times ran an article profiling a local man who was a retired public servant (a fire-fighter, I believe) who liked to dig up local bottle pits throughout the city. The article portrayed the gentleman, who was very enthusiastic about what he did, as a local hero who was bringing to light the citys unknown history. Local archaeologists were appalledhere was a man who was destroying archaeological sites to build a personal collection of artifacts to display at his house.

Archaeologists, as you will see if you read beyond the preface, are very conscious of the fact that every time they excavate a site, that site is destroyed. Excavation is a process through which we dismantle the spatial relationships between things in the ground that have been created by people, the elements, and time. Archaeologists excavate not to find things, but to understand how things got where they are, what that may tell us about how they were used, and what they meant to the people who either intentionally or unintentionally left them there. We use detailed record keeping to ensure that the spatial relation ships between things found in the earth are documented for others to access and that the materials we find are kept in a facility that allows future scholars access to those materials.

Archaeologists do not sell things, and they do not keep things. They do not build vast private collections of the things they have found. Because our field methods are time consuming, we take a lot longer to dig a site than a retired guy with a shovel. In fact, it was the recognition that the retired guy with the shovel was destroying more sites than the combined excavation power of New Yorks archaeological community could scientifically excavate in the same block of time that led to an archaeological backlash against the bottle-hunting local hero on the New York Times website.

At the time, I read through the postings to see what this whole blow-up had to say about the relationship between archaeologists and the general public, and I noticed several disturbing trends. First, the archaeologists tended to come off as self-righteous pinheadsand secondly, and more importantly, the non-archaeological respondents were greatly in favor of the local hero and condemned the archaeologists as, well, selfrighteous pinheads.

Being an archaeologist myself, I recognized that my colleagues earnestness and passion were being misunderstood and misinterpreted by other readers. However, I also realized that unlike the local hero, who enthusiastically talked about the visceral thrill of finding old objects in the ground, the archaeologists had universally failed to communicate equal enthusiasm for their subject in a way that was accessible. They only managed to look like they were selfishly hogging all the archaeological fun for themselves.

The general public is generally receptive to and interested in archaeology. What we do is pretty cool. We find stuff in the ground and then come up with feasible stories about how it got there and what it means. Its sort of magical or at least, very Sherlock Holmeslike. Our bottle-hunting friend had managed to capture the coolness-of-finding-stuff part of archaeology; the archaeologists failed to convey why- its-the-finding-out-how-it-got-there-and-what-it means-that-is-the-more important-part of the argument.

The chances are, if you are reading this book, it is because you are taking an introductory course in archaeology, and youve chosen to take this class because it seems like a more interesting way to fulfill a social sciences breadth requirement than say, sociology or political science. You would, incidentally, be quite right. You are then, not only a potential anthropology major or future archaeologist, you are also a potential supporter of archaeology long after you leave the university and do something lucrative like practice law or plumbing. It is not merely benevolence to my discipline that I want to instill in you, however. I sincerely believe that thinking like an archaeologist, or learning to see the social world as also a physical one, is a valuable tool for anyone. An introductory course can either solidify your interest in this subject or send you screaming to Sociology 101.