Contents

Page List

Guide

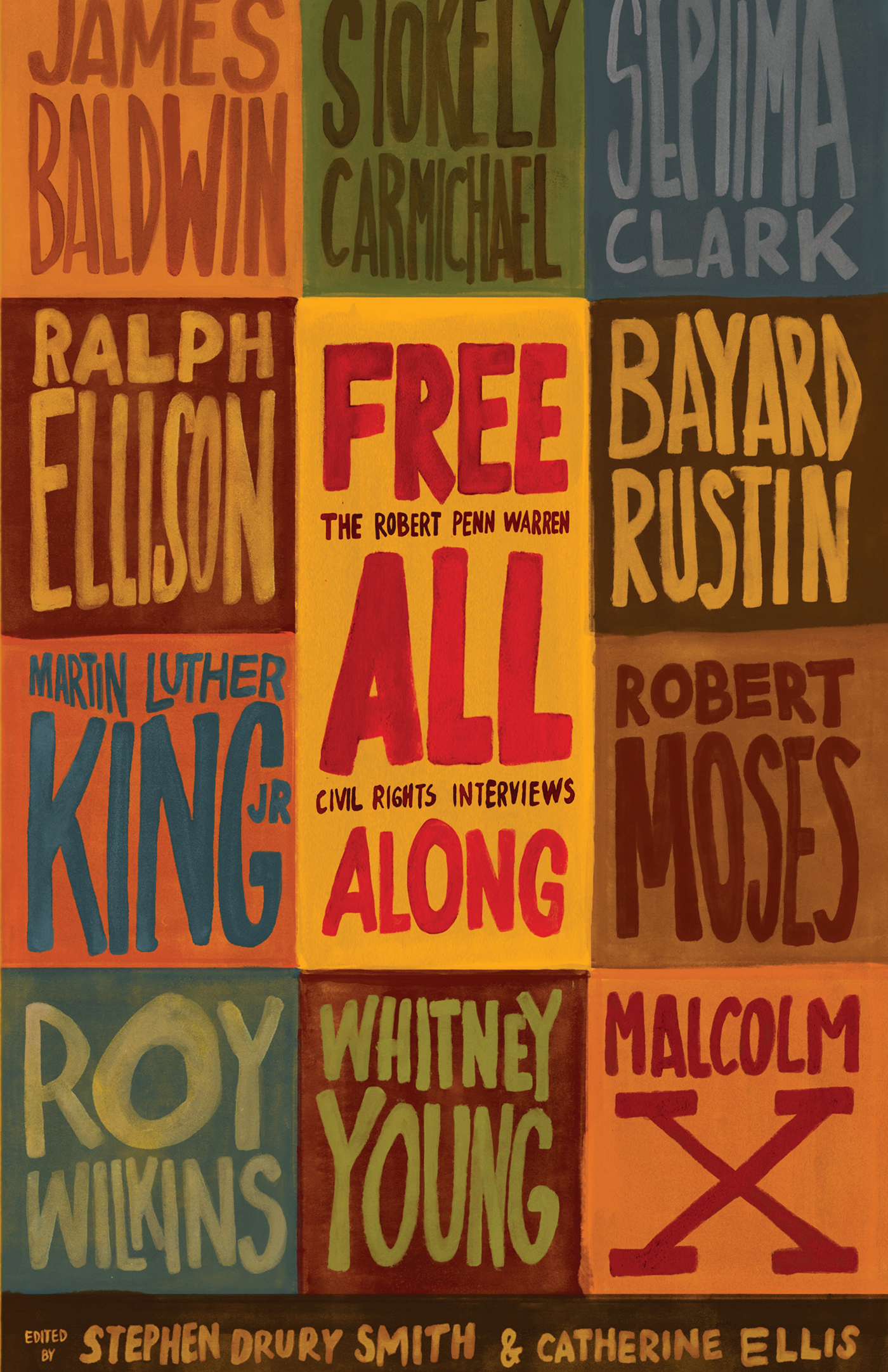

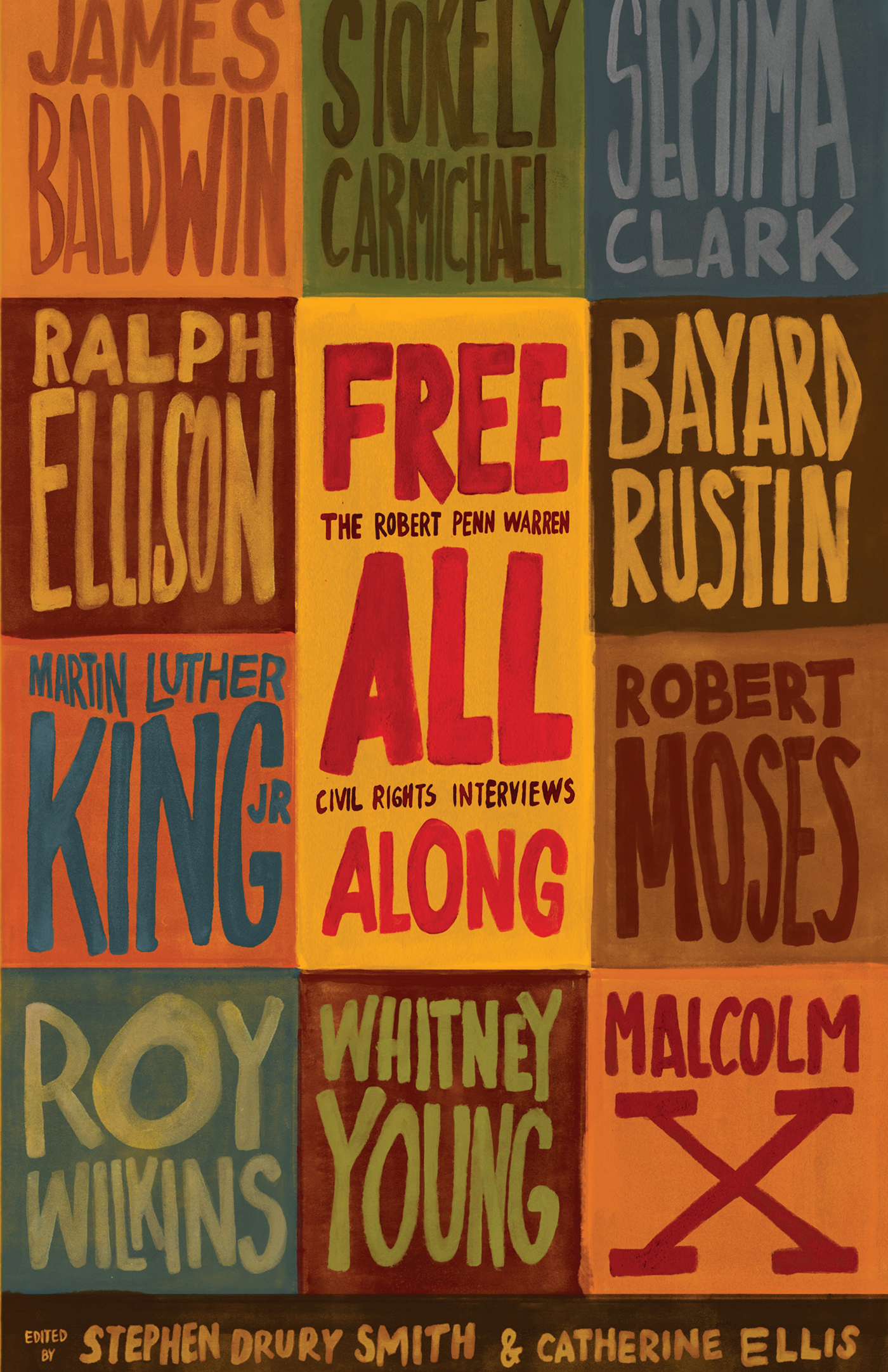

Free All Along

Also Edited by Catherine Ellis and Stephen Drury Smith

After the Fall: New Yorkers Remember September

2001 and the Years That Followed

(with Mary Marshall Clark and Peter Bearman)

Say it Loud: Great Speeches on Civil Rights and

African American Identity

Say it Plain: A Century of Great African American Speeches

Free All Along

The Robert Penn Warren Civil Rights Interviews

Edited by

Stephen Drury Smith and

Catherine Ellis

2019 by Stephen Drury Smith and Catherine Ellis

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form,

without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to:

Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street,

31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2019

Distributed by Two Rivers Distribution

ISBN 978-1-59558-818-0 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-59558-982-8 (ebook)

CIP data is available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Composition by dix!

This book was set in Adobe Garamond

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Contents

Introduction

In 1964, the celebrated Southern writer Robert Penn Warren set out on a fact-finding mission with a reel-to-reel tape recorder. His aim was to interview leaders of what some were calling the Negro Revolution. Warren wanted to find out what their goals were and how they planned to achieve them. He was on assignment for Look, a popular national magazine. But the project would also result in an unusual, 450-page meditation on American race relations called Who Speaks for the Negro?

The book was published in 1965. Some critics praised it as a valuable window into the African American experience and the freedom movement. Others thought it poorly organized and unrevealing. Who Speaks for the Negro? was out of print for decades until Yale University Press reissued the book on its fiftieth anniversary.

Warren was greatly disappointed by the relatively poor sales. Albert Erskine at Random House explained the problem in a letter: The real trouble, of course, is the absolute glut of reading material on the subject and the feeling of many people that they have read all they intend to about it.

Warren interviewed nearly four dozen civil rights activists, leaders, and writers for Who Speaks? He retained the original recordings and their typed transcriptions, which are now held by the libraries of Yale University and the University of Kentucky. Vanderbilt University has digitized the interviews and created a comprehensive website with transcripts and archival material. A selection of these revealing, wide-ranging conversations is edited and presented here.

In Who Speaks? Warren wove together interview excerpts with his own impressions of the speakers and larger observations about the movement. In this edited anthology the focus is on the interviews themselves, framed by some biographical and historical context. They are arranged chronologically. This anthology also features two interviewswith Andrew Young and Septima Clarkleft out of Warrens book.

Free All Along draws its title from Warrens interview with the writer Ralph Ellison. It offers the opportunity to hear directly from a range of history-making African Americans at a critical time in the civil rights movement. A major contribution in their own right to our understanding of the black freedom struggle, these remarkable long-form interviews also have pressing relevance today.

When Warren hit the road in the early months of 1964, the civil rights movement was convulsing American society, especially in the Jim Crow South. Over the previous decade, activists had launched boycotts, protest marches, lunch counter sit-ins, voter registration drives, rallies, and mass meetings, all to demand equal rights and equal protection under the law for black Americans. In many communities, whites responded with rage and lethal violence. In 1961, African American and white Freedom Riders challenged segregation on interstate buses. In Alabama and Mississippi, they were attacked and jailed, and one of their buses was torched. In 1962, white rioters tried to block an African American student named James Meredith from entering the University of Mississippi. In 1963, four black girls were murdered in the bombing of Birminghams Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) organizer Medgar Evers was murdered outside his home in Jackson, Mississippi, and activist Fannie Lou Hamer was badly beaten by police in a Winona, Mississippi jail. Also in 1963, Martin Luther King delivered his I Have a Dream speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and President John F. Kennedy sent Congress his proposed civil rights legislation. These critical events were the backdrop to Warrens journey of investigation.

Look published Warrens lengthy article The Negro Now in March 1965. Who Speaks for the Negro? was published by Random House two months later. At the time, Warren had long been regarded as one of the nations foremost authors and poets. His best-known novel, All the Kings Men, won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize. It was made into a movie that won the 1949 Academy Award for best picture. Warren won the Pulitzer Prize in poetry in 1958 and again in 1979. He is the only person to have won the prize for both fiction and poetry.

Robert Penn Warren was born in Guthrie, Kentucky, in 1905, the son of a businessman and a schoolteacher. He grew up on a tobacco farm, where his grandfathersboth of whom had fought for the Confederacytold stories of the Civil War. Warren attended Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he met other Southern writers who would go on to form a literary group called the Agrarians. In 1930, they produced a collection of essays, IllTake My Stand, proclaiming the virtues of agrarian life over modern industrialization. Warrens contribution was an essay called Briar Patch, which historian David W. Blight describes as an ambivalent and poorly argued defense of segregation in which Warren contended that rural life best suited the temperament and capacity of Southern blacks. Warrens attitudes about race, however, became increasingly progressive over the decades; literary scholar David A. Davis says Warren came to condemn segregation as dangerous and damaging to both blacks and whites. But as commentators worked to understand Warrens conceptions of racein both his fiction and his journalismmany inevitably cited Briar Patch. In Blights words, the essay haunted Warren for the rest of his life.

Warren left the South to study at the University of CaliforniaBerkeley, Yale, and Oxford, where he was a Rhodes scholar. He taught at several colleges and universities, finally landing back at Yale, where he was on the faculty from 1951 to 1973. He died in 1989 in Stratton, Vermont.