Who Speaks for the Negro?

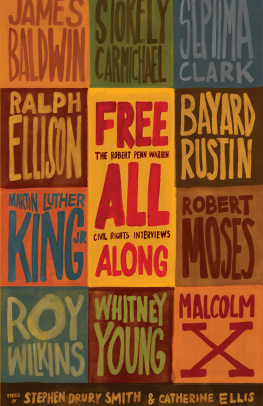

WHO SPEAKS FOR THE NEGRO?

Robert Penn Warren

With an Introduction by David W. Blight

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of James Wesley

Cooper of the Class of 1865, Yale College.

1965 edition published by Random House. 1993 copyright renewed, Eleanor Clark Warren.

Reprinted by Yale University 2014.

Introduction copyright 2014 by David W. Blight.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or

sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

The author and publisher wish to thank the following for permission to use material quoted:

DIAL PRESS, INC. Nobody Knows My Name by James Baldwin, Copyright 1961 by James Baldwin; and Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind from The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin, which appeared in The New Yorker, November 17, 1962.

FIDES PUBLISHERS, INC. The New Negro, edited by M. H. Ahmann.

GROVE PRESS, INC. The Subterraneans by Jack Kerouac. Copyright 1958 by Jack Kerouac.

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LTD. Race and Colour in the Carribean by G. R. Coulthard.

STUDENT NONVIOLENT COORDINATING COMMITTEE The Graham letter, originally published in the Student Voice publication.

THE COND NAST PUBLICATIONS INC. Disturbers of the Peace: James Baldwin by Eve Auchincloss and Nancy Lynch Handy (Mademoiselle, May 63). Copyright 1963 by The Cond Nast Publications, Inc.

THE VILLAGE VOICE View of the Back of the Bus by Marlene Nadle. Copyright 1963 by The Village Voice, Inc.

WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY The Mark of Oppression by Abram Kardiner and Lionel Ovesey. A Meridian Book.

Design by Tere LoPrete. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014932435

ISBN 978-0-300-20510-7 (pbk.)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

With thanks to all those who speak here

I believe that the future will be merciful to us all. Revolutionist and reactionary, victim and executioner, betrayer and betrayed, they shall all be pitied together when the light breaks...

A character in Under Western Eyes,

by JOSEPH CONRAD

Contents

Note on the Digital Archive

The original audiotapes and other research materials related to Robert Penn Warrens Who Speaks for the Negro? are held by the University of Kentucky and the Yale University Libraries. In cooperation with these institutions, the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities and the Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries at Vanderbilt University created a complete digital archive, which is fully searchable and available to the public at http://whospeaks.library.vanderbilt.edu/.

The Who Speaks for the Negro? Digital Archive consists of the original reel-to-reel recordings that Warren compiled for each of his interviewees. In addition, it incorporates all print materialstranscripts, letters, book reviews, and morerelated to the project. The archive also includes interviews that are not in the book (for example, a conversation with Septima Clark). Readers of Who Speaks for the Negro? are invited to listen to the original interviews and peruse the related documents in order to deepen their understanding of the project, its characters, and the historical period from which it emerged.

Mona Frederick, Executive Director

Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities

Vanderbilt University

Introduction

Jack Burden Goes on the Road and Learns His History

DAVID W. BLIGHT

Knowing is, Maybe, a kind of being, and if you know, Can really know, a thing in all its fullness, Then you are different, and if you are different, Then everything is different, somehow too.

Robert Penn Warren, Brother to Dragons, 1953

The will to power, grisly as it appears in certain lights, can mate, if uneasily, with love of justice and dedicated self-interest.

Robert Penn Warren, Who Speaks for the Negro?, 1965

Robert Penn Warren loved the philosophy and practice of pragmatism, considered imagination perhaps the greatest human capacity, hated sentimentality and piety, breathed irony in and out as though it were air itself, believed human nature to be a largely dark and evil realm, and contended that no human could live effectively without a deep and abiding sense of history. And he thought history itself an essentially tragic story, with humans constantly struggling against their fate however they could know it. Still, in 1965 at a triumphal juncture of the Civil Rights Movement in America, a time when irony and circumspection about race were not in vogue, Warren, at age sixty, published an extraordinarily unusual and hopeful book about race relations, leadership, power, and ultimately, about himself.

There is no other book quite like Who Speaks for the Negro? Published on May 27, 1965, by Random House, Who Speaks is a very personal and hugely ambitious creation by a then mature and accomplished white, Southern, American man of letters. Warren is the only American writer to receive the Pulitzer Prize in both fiction and poetry (twice in poetry). Few American writers of the mid-twentieth century worked in so many genres with such distinction as did Warren. A novelist, poet, critic, -and nonfiction essayist, he was also in his own way a self-styled historian, deeply committed in all forms of writing to probing the very nature of the past, the ways it is known, narrated, and felt across time and in daily life. Few American writers have written with such imagination about the relationship of past and present, about the ancient connections of myth and history. That Warren would set out in 1964 on such a remarkable journey, tape recorder in his arms, to interview every major leader of the civil rights revolution, as well as many students and unknown activists, is both astonishing and an unsurprising piece of this writers long personal trajectory. From the grandson of a Confederate veteran steeped in the mores of the Jim Crow South to a world-class writer and white racial liberal (although he disliked such labels) of the 1960s, Warren traveled great ideological and imaginative distances. But he was always, in part, where he was from, and in Who Speaks, as he strove to uncover the thoughts and emotions of his subjects, he sought equally to know his own. This is no mere oral history; it is a personal testament. At times he simply lets his subjects speak, but often Warren imposes his own voice and personality onto the text, with results that some have admired and others have not.

Warren was a prodigy. Born in 1905 and raised in Guthrie, Kentucky, a small railroad junction town, he skipped two grades and graduated from high school at sixteen, just across the border in Clarksville, Tennessee. His boyhood dream was to go to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, and he was already accepted when, in a freak accident, his younger brother, Thomas, threw a baseball-size piece of coal over a hedge, hit Robert Penn in the face, and blinded him in his left eye. The injury badly affected the young Warren psychologically for a while, but he soon entered Vanderbilt University as a mere teenager. There he came

Next page