The Twilight of the Goths

The Rise and Fall of the Kingdom of Toledo

c. 565711

By Harold Livermore

The Twilight of the Goths

The Rise and Fall of the Kingdom of Toledo

c. 565711

By Harold Livermore

First Published in the UK in 2006 by Intellect Books, PO Box 862, Bristol BS99 1DE, UK

First published in the USA in 2006 by

Intellect Books, ISBS, 920 NE 58th Ave. Suite 300, Portland, Oregon 972133786, USA

Copyright 2006 Intellect Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover Design: Gabriel Solomons Copy Editor: Holly Spradling

Typesetting: Mac Style, Nafferton, E. Yorkshire

Electronic ISBN 1-84150-973-6 / ISBN 1-84150-966-3 1-84150-966-3 / 9781841509662

Printed and bound in Great Britain by 4 Edge Ltd

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

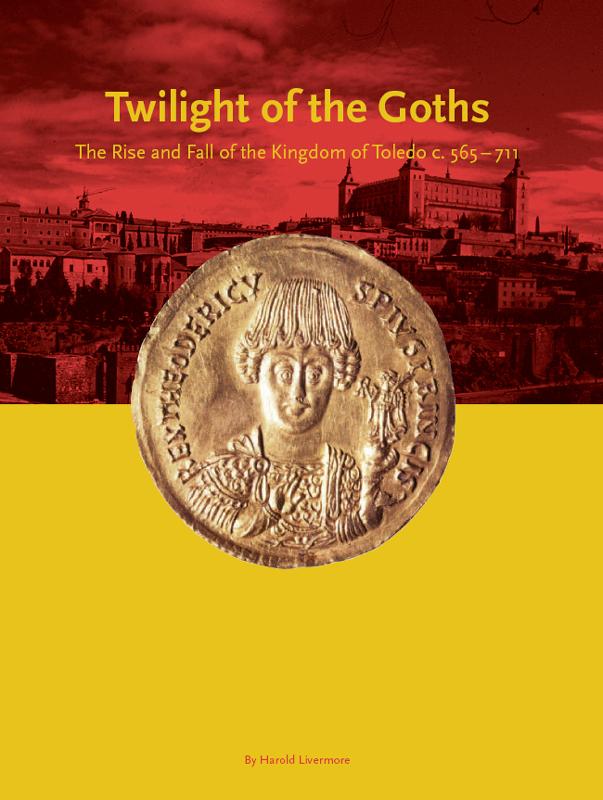

El Grecos Toledo, by courtesy of Sr L. Caballero, Museo de El Greco, Toledo; The helmet, after Condurachi and Daicoviciu; The page from Ulfila, from the University Library, Uppsala, Sweden; The solidus of Theoderic is from the National Numismatic Museum in Rome; The votive crown of King Recceswinth, by permission of the National Archaeological Museum, Madrid; The remaining photographs are by courtesy of the Spanish Tourist Office in London.

FOREWORD

If an explanation is needed, I applied the title of this monograph to a review of essays on The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century, edited by Peter Heather, in 1999, in an ethnographical series (Studies in Historical Archaeoethnology, Vol. 4, Woodbridge, Boydell). My column, however, appeared in the Times Literary Supplement under a different heading. As is usual, some of the contributions were excellent, others less so. I thought that the general effect gave too much importance to the tribal origins of the Goths as opposed to the formative experience of service in the late Roman army. I could not set out my reasons in a review, and it seemed incumbent to provide a balanced version by one author. My balance is from having published general histories of Portugal and of Spain, and of the formation of both modern Peninsular states, recalling the fact that the Germanic domination of the Iberian Peninsula includes also that of the Sueves. The suggestion comes from Professor Keith Cameron, who has read my text to the the last comma to my benefit. I alone am responsible for surviving errors.

Harold Livermore

Sandycombe Lodge, Twickenham

INTRODUCTION

When Luis Dez del Corral wrote his Rape of Europe in 1954, he asked: Who were these Visigoths who failed our Europe so abjectly? Were they already Spaniards?

In European terms, this begs other questions: Were there already Spaniards in the sixth century? Were those Visigoths who sacked Rome in 410 and abjectly lost Spain to the Muslims in 711 the people, who emerged as barbarians from what is now TransDanubian Romania, also the same people as those who were idealized in fifteenth century Spain as the very pattern and mould of Castilian nobility and chivalry? Tempora mutantur et nos mutamur in illis. Change, politicians often say, is to be welcomed: they are in a position to profit by its favours and soften its reverses. Many Romans were inclined to seek the Golden Age in the remote past, as did Don Quixote in addressing his audience of shepherds: he hoped, with divine aid, to restore it.

Divergent and opposing perceptions of the Visigoths still exist. For those who follow the destinies of the Roman world they are unquestionably barbarian intruders. But Germanists may consider the Visigoths almost as renegades, detached from the northern world. The difference is largely accounted for by the fact that remains of the German world are mainly physical, while Romanism survives as an intellectual force. As St Isidore, the great figure of the seventh century, foresaw, the future lay in the fusion of Roman culture with Gothic strength. The great champion of the Roman tradition could not have foretold the disaster that followed two generations after his death.

Those who follow the Roman tradition tend to seek the special nature of the Visigoths in their remote barbarian past. Yet they rarely dissent from the view that there is little trace left of the Visigothic presence in the territories they once possessed. It is therefore necessary to temper the search for some essential clue to the Visigoths by emphasizing the influence on them of their prolonged contact with Rome, and particularly their service in the Roman army whose habits and outlook they adopted, not to mention that of the wives, Romanized or not, they acquired in the course of their wanderings, which led them to the Spains, where they founded their kingdom of Toledo. With this in mind, we may start with the later Roman world, on which they impinged with such devastating if transitory effect.

The Romans came into direct contact with the Visigoths in the time of Constantine I, who crossed the lower Danube into Transylvania and contracted some Visigoths to serve in his Eastern army. At that time most of the Spains had been subdued, the east and south for nearly half a millennium, and presented no danger to the empire. The eastern seaboard had been taken over as a protectorate from the Greeks, who gave it the name of Iberia, related to the great River Ebro. The south had been conquered after the defeat of Hannibal in the Second Punic War. The Phoenicians were traders rather than colonists, but their heirs the Carthaginians had at a late stage set up an empire, of which Cartagena, or New Carthage, serves as a memorial. Its main source of wealth had been the native kingdom of Tartessos which controlled the valley of the Baetis, now the Guadalquivir, or Great River by antonomasia. The Romans picked up the names Span and Hispania, which have given Spain and Hispalis, Seville. They continued to distinguish Nearer Spain, or Hither Spain, Citerior, from Hispania Ulterior, Further Spain, what lay beyond. Much of the interior remained unsubdued, if not unvisited, until the last native hero Viriatus was killed by treachery in 136 BC; his Latin name alludes to the Celtic bangles or circlets, viriae, he wore. Roman forces then soon reduced the hill-top settlements of the north-west, leaving only the north coast as the still-militarized frontier or limes.

The process of Romanization began from the south and proceeded up the western side, though less rapidly on the high tableland of the centre, the dry meseta, less amenable to agriculture and more sparsely populated. The Iberian Peninsula was still the Spains, Hispaniae in the plural. They were held together by marchable roads, bridges and posting-houses constructed under the supervision of Roman surveyors and military engineers. Cities and towns copied Roman architecture and institutions and their leaders prized themselves on their Latinity. The south was already accustomed to domination from beyond the seas and acquired Roman dress, language and habits almost everywhere. The Romans favoured flat and arable land and open settlements, so that the fortified hill-tops were either abandoned or greatly modified. In Baetica men wore the toga and went unarmed as in Rome itself. Elsewhere the Roman superstructure overwhelmed the variety of indigenous communities.