Christopher Harding

JAPAN STORY

In Search of a Nation, 1850 to the Present

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Copyright Christopher Harding, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover: Nagaoka no yado, from the series Tales of Ise, 1903, by Kajita Hanko.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Lonard A. Lauder Collection of Japanese Postcards

ISBN: 978-0-141-98536-7

To my parents and to my wife

With love and gratitude

For all the things I can think of

And all those a more perceptive son and husband Would have noticed by now

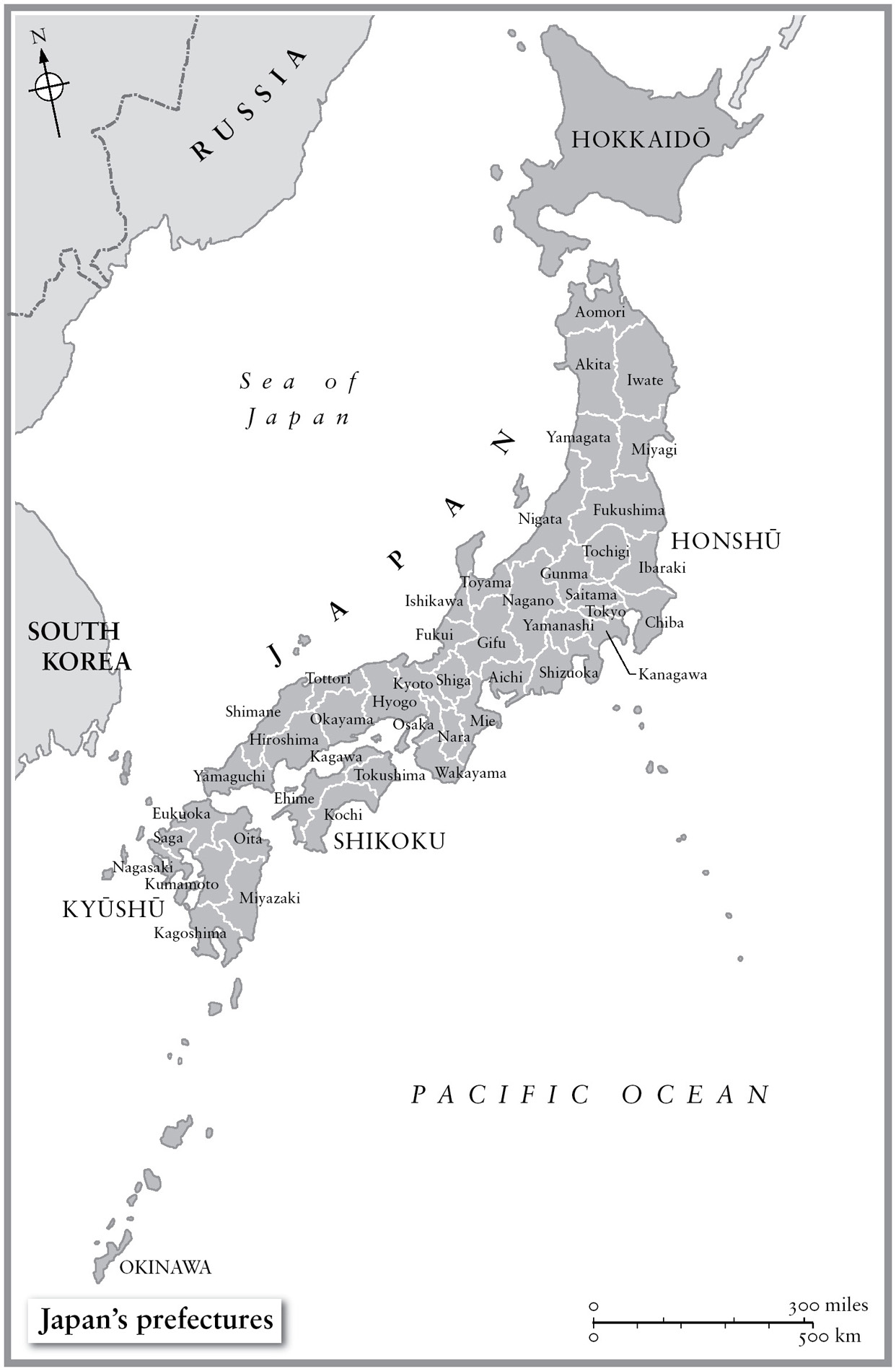

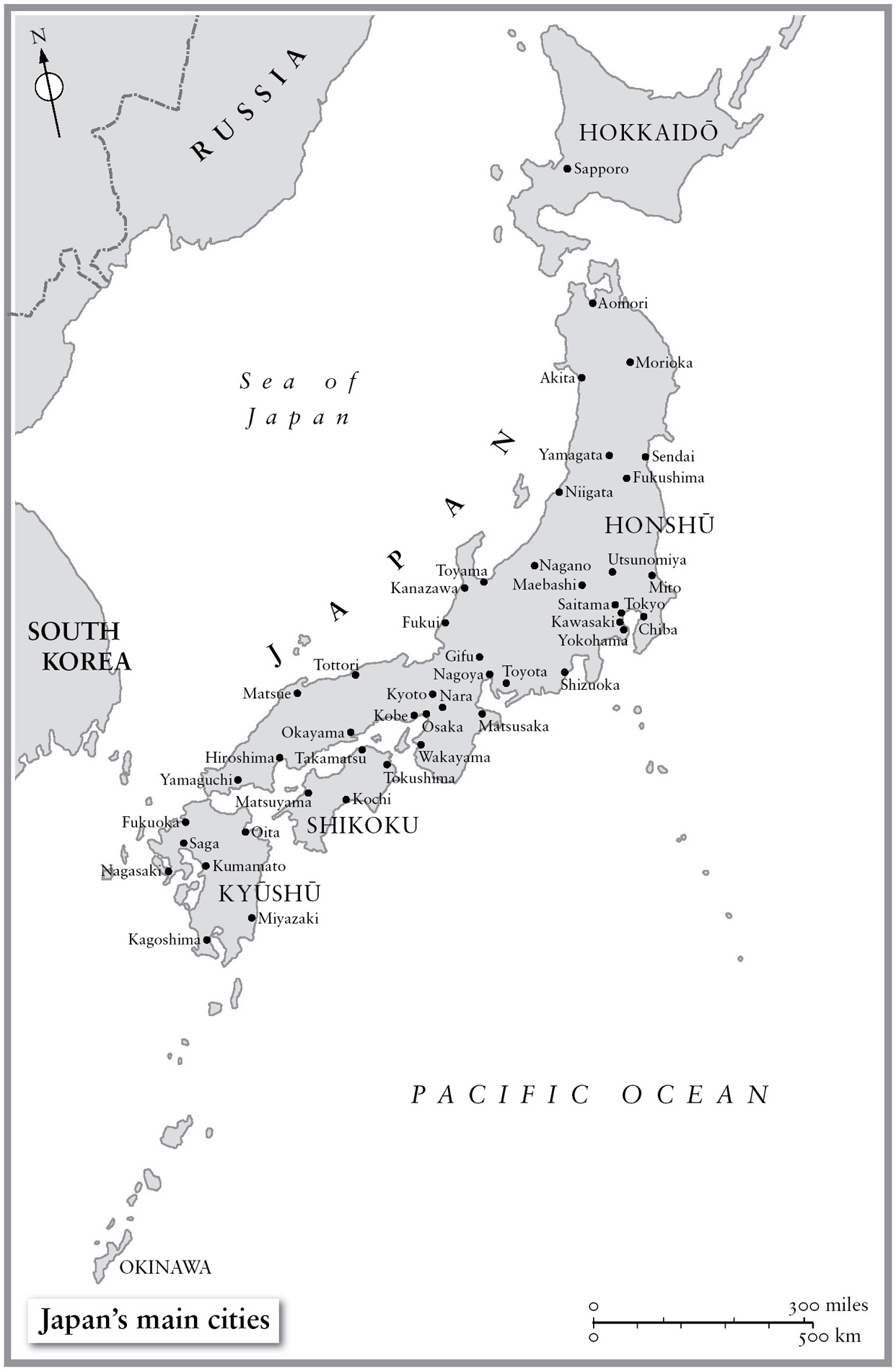

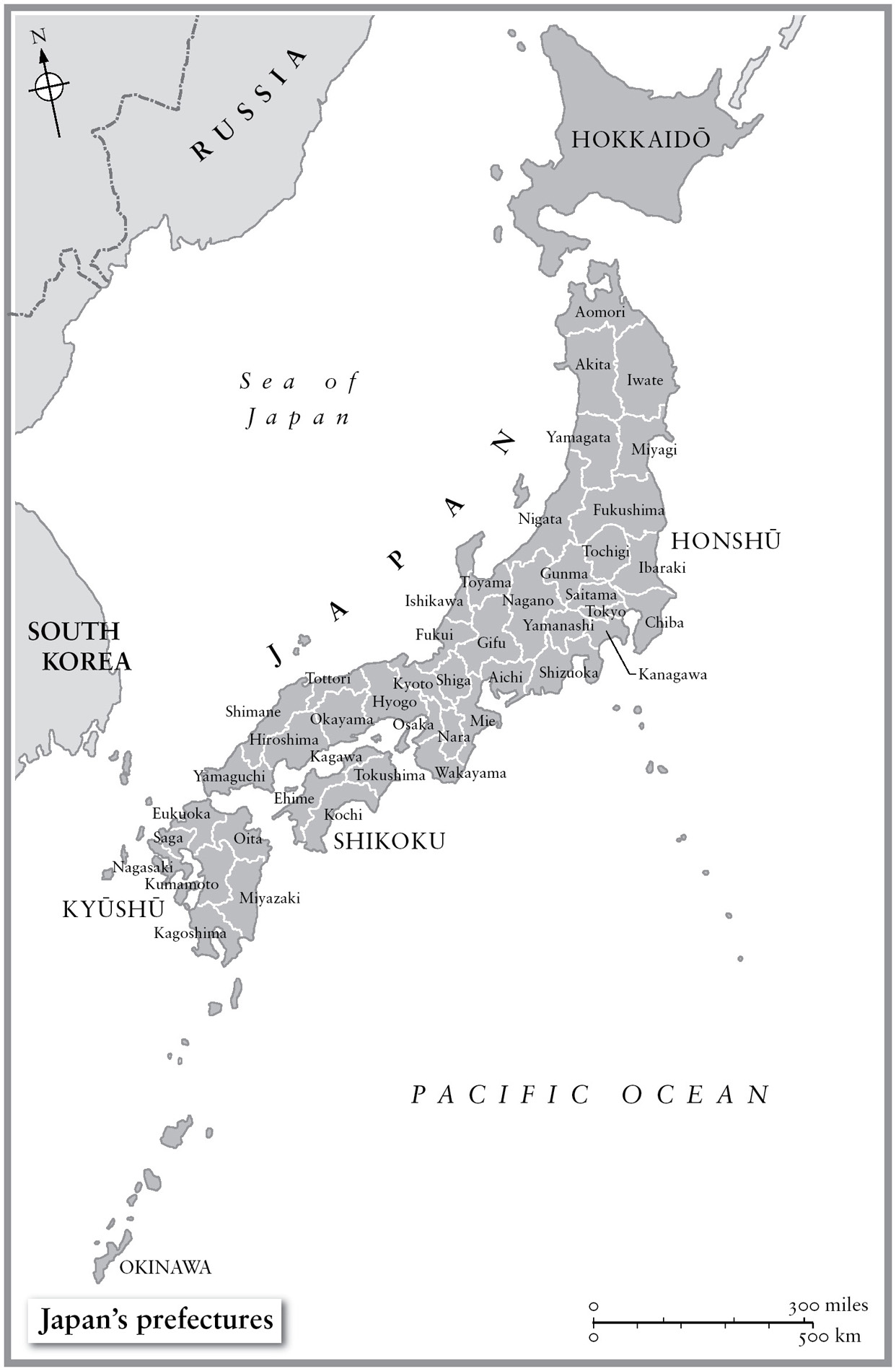

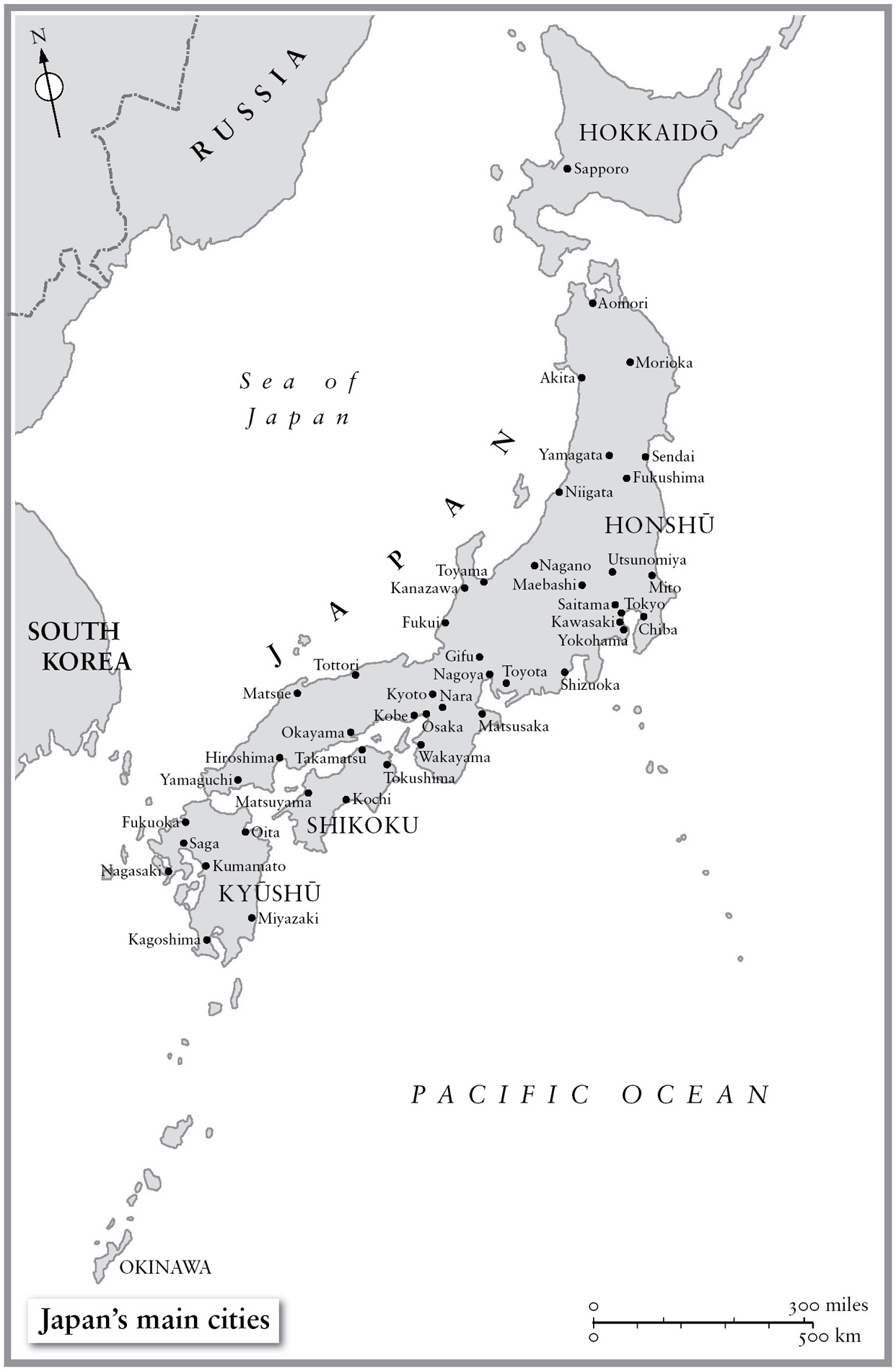

List of Maps

A Note to the Reader

Japanese names appear in this book in the standard Japanese order of family name followed by given name. Where a Japanese scholar is publishing in English, their name appears in the standard English language order of given name followed by family name.

Macrons are used to indicate elongated vowel sounds except in the case of place names that are well established in English (e.g. Tokyo).

Passages have been set in italic where events, conversations between historical characters or storylines from Japanese literature are being paraphrased or condensed.

English translations of Japanese book titles have been given in brackets after the Japanese. Those books that have also been published in English appear in italics. The date of the original publication in Japanese is given in brackets after the title.

PROLOGUE

Harumi and Heisaku

My kimono, the colour of rust. Central Tokyo, cars whizzing around me. Sitting inside a car with my friend, a mountain of boiled eggs in front of us. My sisters sickroom. Standing, staring at her water-blue futon as she sleeps. Shes frowning. Flowers in a garden. Someones fingers. Three men in a coffee shop. Flowers again a field of yellow flowers. Inside a plane. A banyan tree. An Indian bookshop, shelves heavy with books. I worry theyre going to spill down on top of me. A man removing his glasses

Harumi stopped speaking, and opened her eyes. A face appeared briefly in a dusty shaft of daylight: tired but noble, framed by thin grey hair. A black scarf was tucked inside a kimono of dark silk.

Youre ill. Youre suffering.

The mans words were slightly slurred and indistinct; his eyesight had mostly gone, years before, and now a series of strokes were eating away at his powers of movement and speech. And yet this was the softest voice that Harumi had ever heard. She wasnt being handed a diagnosis, nor being idly discussed as a case study. She was being seen, in a way no one herself included had ever managed before. Many years later Harumi remembered that voice as sending cool water coursing through a mind and body so desiccated, so brittle, that she feared the lightest of touches would break her.

The voice belonged to Kosawa Heisaku, a devout Buddhist and Japans first Freudian psychotherapist. Sitting in a chair behind Setouchi Harumi, who was lying on his couch, he stayed mostly silent as she allowed thoughts, images, fantasies and worries to tumble out of her, at random and uncensored, into the musty wooden stillness.

Harumi and Heisaku: two lives overlapping for a few brief months in the mid-1960s which together spanned most of Japans tumultuous modern era. As a boy in the early 1900s, the young Heisakus heart had been set racing by the crackle of gunfire resounding across the fields near his home. Japans new professional, conscript army on manoeuvres, immaculate in European-style uniforms and tiny, tight moustaches, had been hurriedly established a generation before, amidst the menace of heavily armed Western steamships materializing off the countrys coast. This armys stunning victories over China and then Russia were already immortalized in vivid posters and commemorative postage stamps pored over by the young boy and thousands like him. A little over a century later, an octogenarian Harumi would protest against her countrys faded sense of purpose. A precipitous return to nuclear power after triple disasters in 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown threatened, she would say, to further shake peoples confidence in Japan and its leaders. Proposed revisions to Japans pacifist constitution, opening up the prospect of renewed self-assertion in East Asia, seemed to her a poor and dangerous substitute for real political direction.

Heisaku and Harumi: two lives lived at the reflective, apprehensive fringes of modern Japan. Harumi was in her forties when they met, a novelist approaching her lowest point just as all around her the heyday of the akarui seikatsu the bright life animated a city many of whose neighbourhoods had been reduced to ashes and bone just twenty years before. Tokyo was now the pulsating centrepiece of Japans economic miracle. Music and fashion filled the bars and streets, critics hailed a golden age of literature and cinema, and brand new super-fast shinkansen trains were being rolled out just in time to serve as a symbol of Japans progress as the worlds athletes and sports fans limbered up for the citys hosting of Asias first Olympic games.

Harumi had in recent years come through the ignominy still attached to divorce. She had successfully battled accusations of pornography against her early writing literature remained for the most part a mans world, with intimate writing by women not always welcomed. And she had built friendships amongst Tokyos celebrated community of writers and artists. She would soon stand next to Mishima Yukio as he rang the bell at the home of Kawabata Yasunari, his hand clenched white-knuckle tight around a congratulatory bottle of sake as he steeled himself to celebrate with Kawabata the Nobel Prize in Literature that he felt should have been his. Harumi had found richness too in her relationships with the tangle of competing men who inspired one of her greatest works: Natsu no Owari (The End of Summer).

And yet of late she had started to worry her friends. A wry, probing conversational style had become more and more intense, verging on the obsessive. She would start talking and be unable to stop, sometimes running on for a whole night. One day she came close to injuring herself absently trying to walk up the descending escalator in one of Tokyos exclusive department stores.

The old consulting room to which all this had led her, with its ageing couch and chair, testified to a life of great industry drawing to a marginal, faintly disappointed close. Heisakus bookshelf proudly announced the latest psychological insights of the 1930s, 40s and 50s a series of exciting new dawns already for the most part forgotten by a newer generation of psychologists and therapists. Outside, beyond the curtained window, lay the Tokyo suburb of Den-en-chfu. Japans pre-war attempt at the British and American garden city ideal of affordable houses set out along wide tree-lined streets had long since turned into a celebrity- and politician-infested Beverly Hills.