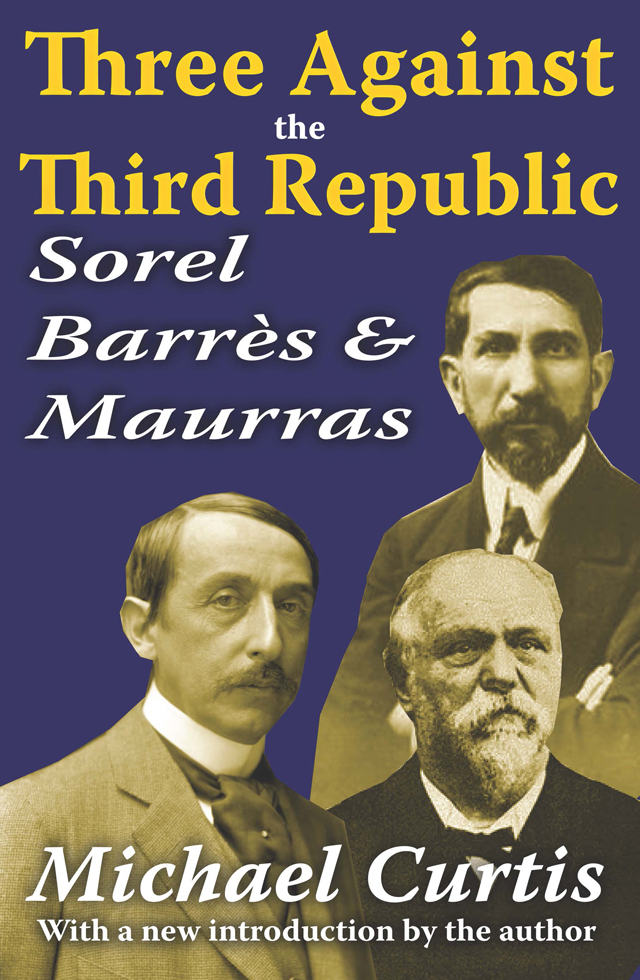

Three Against the Third Republic

Three Against the Third Republic

Sorel Barrs & Maurras

Michael Curtis

With a new introduction by the author

Originally published in 1959 by Princeton University Press.

Published 2010 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2010 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2010005574

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Curtis, Michael, 1923

Three against the Third Republic: Sorel, Barrs, and Maurras / Mi

chael Curtis.

p. cm.

Originally published: Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4128-1430-0 (alk. paper)

1. France--History--Third Republic, 1870-1940. 2. France--Politics

and government--1870-1940. 3. Sorel, Georges, 1847-1922. 4. Barrs,

Maurice, 1862-1923. 5. Maurras, Charles, 1868-1952. 6. Intellectuals

-France--Biography. 7. Democracy--France--History. I. Title.

DC340.C8 2010

944.081--dc22

2010005574

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-1430-0 (pbk)

To six engaging lovers of life

Beth and Victor

Lucianna and Johnny

Mary and Irving

Contents

Guide

The great French historian Jules Michelet once wrote that history becomes useless unless one imbues it with the sorrows of the present. With this advice it is salutary to review the place of the three central figure studied in this book, Charles Maurras, Maurice Barrs, and Georges Sorel, in the extraordinary diversity of French political thought and political history in the twentieth century, and more especially to evaluate their intellectual heritage and the extent to which they can be held responsible for contributing to past and present sorrows. This introduction therefore concentrates on those persons and groups who have been influenced by the three writers rather than attempting to provide a comprehensive analysis of French thought.

France is not the only country in which intellectuals have sought to participate in or attempted to influence political action. Nor is it unique in some of its intellectuals playing a questionable role in writing enthusiastically about or becoming complicit with anti-democratic, authoritarian, and anti-Semitic regimes, ideologies or movements. Yet French writers, including those admired and honored for their literary skill, have been conspicuous in playing this role. Moreover they have often done so without heed or concern for the consequences of their activity. The political prejudices of some French intellectuals, some of them fascinated by fascism, all too often prevailed over moral principle in their declamations against their own times and society. The fabric of the vision of those twentieth-century writers was at times more the outcome of phrases and abstractions than of limpid common sense and reality.

The reissue of this book provides a welcome opportunity to consider the impact of the incessant attacks on liberal democracy and on what they considered the state of French civilization and culture by Maurras, Barrs, and Sorel. On this issue and on many others the three writers influenced nationalist, Catholic, and extreme right-wing thought and the action of groups and individuals in France, and to some extent abroad, for most of the twentieth century and even into the twenty-first. The three writers had only a negative impact on French left-wing writers and groups and thus they are not central to this particular study. However, in light of the intense twentieth-century conflicts within French society and among its political ideologies, parties, and organizations a review of the writings of our three political thinkers can help understand more fully the controversial and diverse positions of later French political theorists. The book examined their writings up to 1914. A brief summary of their writings including those after 1914 can set the stage for the evaluation of those positions.

Charles Maurras (1863-1952) continued throughout his life his self-declared mission to defend French civilization by his relentless attack on the Third Republic and its politicians, by his invective against the parliamentary and democratic system, his diatribes against political opponents, and his vilification of Jews. He persevered, in countless articles in his journal, LAction franaise, and his many books, in advocating his counter-revolutionary themes for restoration of monarchy in France, political Catholicism, integral nationalism, organic unity, hierarchical social order, and condemnation of Jews. Maurras was obsessed from his early years with combating Romanticism, the French Revolution, individualism, and Jews. His anti-individualism and his anti-revolutionary ideology were linked with his anti-Semitism. As early as 1895 he wrote that all individualist theory was of Jewish making. Moreover, he argued that in the Jewish law and prophets were to be found the first expressions in antiquity of the individualism, egalitarianism, humanitarianism, and social and political idealism that were to mark 1789 (the French Revolution).

Maurras remained an intransigent doctrinaire, convinced of his perfect wisdom and perfect virtue while assuming an attitude of haughty superiority. For Maurras who early had lost his hearing intellectual discussion was truly a dialogue of the deaf. His doctrinaire nationalism was founded on the classical values he admired, the values of authority and hierarchy he perceived in ancient Greece of the Hellenic period and to a lesser extent in Rome. Unrelentingly opposed to Romanticism, he defined intelligence as a way to choose, to organize into a hierarchy and put in order values, as well as to re-establish the proper order of things in the same way nature had intended it from eternity.

Raymond Aron remarked that Maurras who certainly held an important place in the intellectual history of France in the first half of the twentieth century, continued to give his morning lessons and political directives to his disciples. His antisemitic invective influenced many of the later writers mentioned in this introduction, such as Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Louis-Ferdinand Cline, Robert Brasillach, and Lucien Rebatet, all men of intemperate minds and strong passions.

Maurrass first main target had been Alfred Dreyfus. Believing that France was under threat from foreigners, especially Jews, Maurras approved of the condemnation of Dreyfus in 1894 and regarded Colonel Henry who had forged evidence as a true patriot. His declared position was one of raison dtat; he argued any review of the Dreyfus case would be detrimental to the interests of France. National interest was more important than justice. Maurrass journal, LAction franaise , which in the 1930s had a circulation of over 30,000, continued to attack Dreyfus even after the latters death on July 14, 1935. The Dreyfus Affair, Maurras argued, had led to anti-patriotic, anti-militarist, anti-Catholic, and anti-national manifestations. He noted the coincidence that Dreyfus had died on the 146th anniversary of the taking of the Bastille in 1789. On Maurrass own conviction for complicity and intelligence with the enemy in January 1945, he uttered the famous words, It is the revenge of Dreyfus. Ironically, Dreyfus had been charged with the same offense fifty years earlier. If Maurras did not accept Nazi ideology or engage on behalf of a Nazi crusade he was as relentless in his attacks on Jews as were the Nazis. The apparent difference is that his anti-Semitism was expressed more in cultural or rational terms than in biological racism. Notwithstanding, Maurras was convinced that Jews were conspiratorial by nature with their Oriental spirit. Though he did not propose their extermination he had no sympathy for the fate of Jews murdered in the Holocaust.