Edward Sorel is an illustrator, caricaturist, and cartoonist whose satires and pictorial essays have appeared in many, many places, among them Vanity Fair, The Atlantic,The Nation, and The New Yorker, for which he has done numerous covers. He lives in New York in the apartment that he shared with his wife and sometime writing partner, Nancy Caldwell Sorel.

1

Portrait of the Old Lefty as a Young Lefty

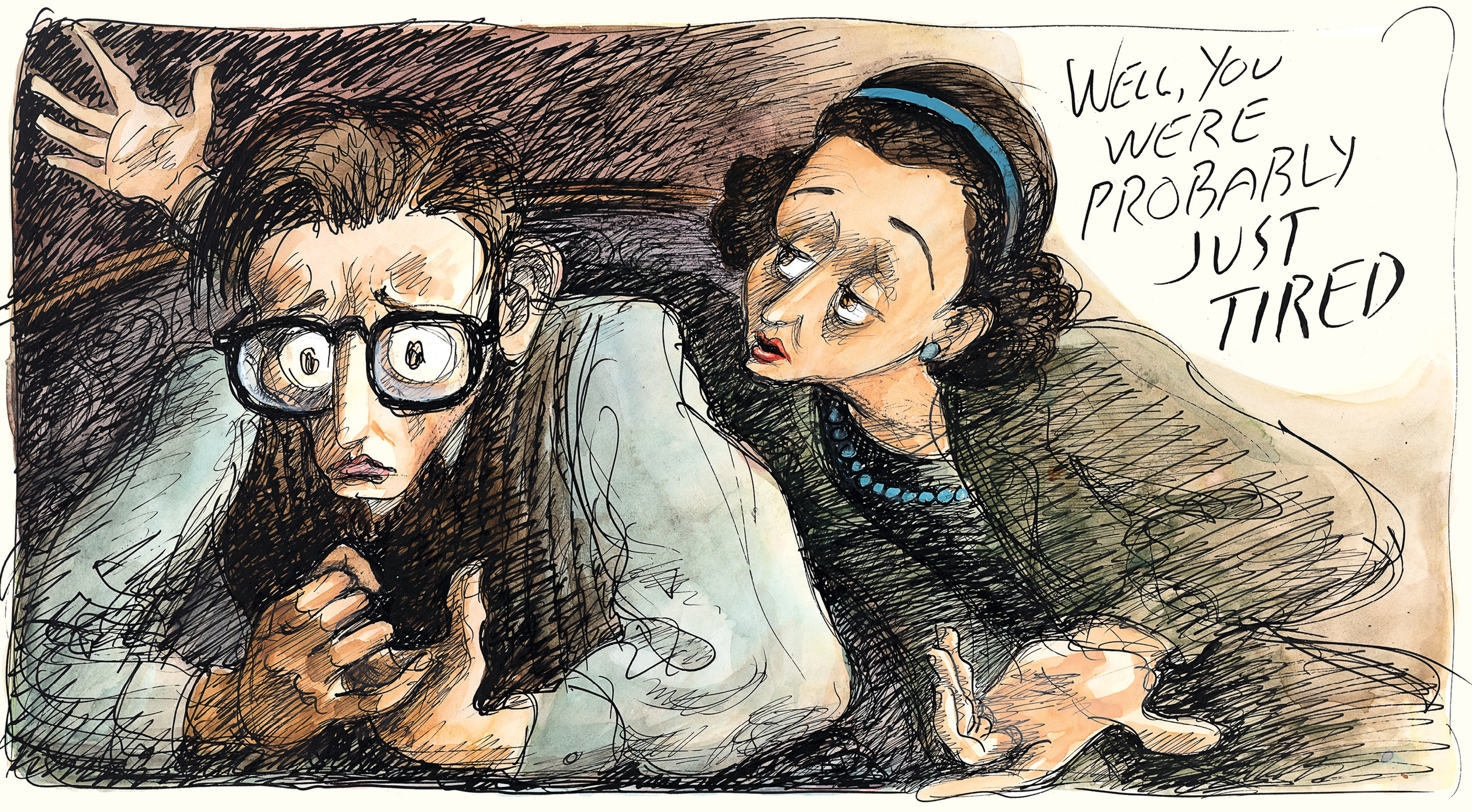

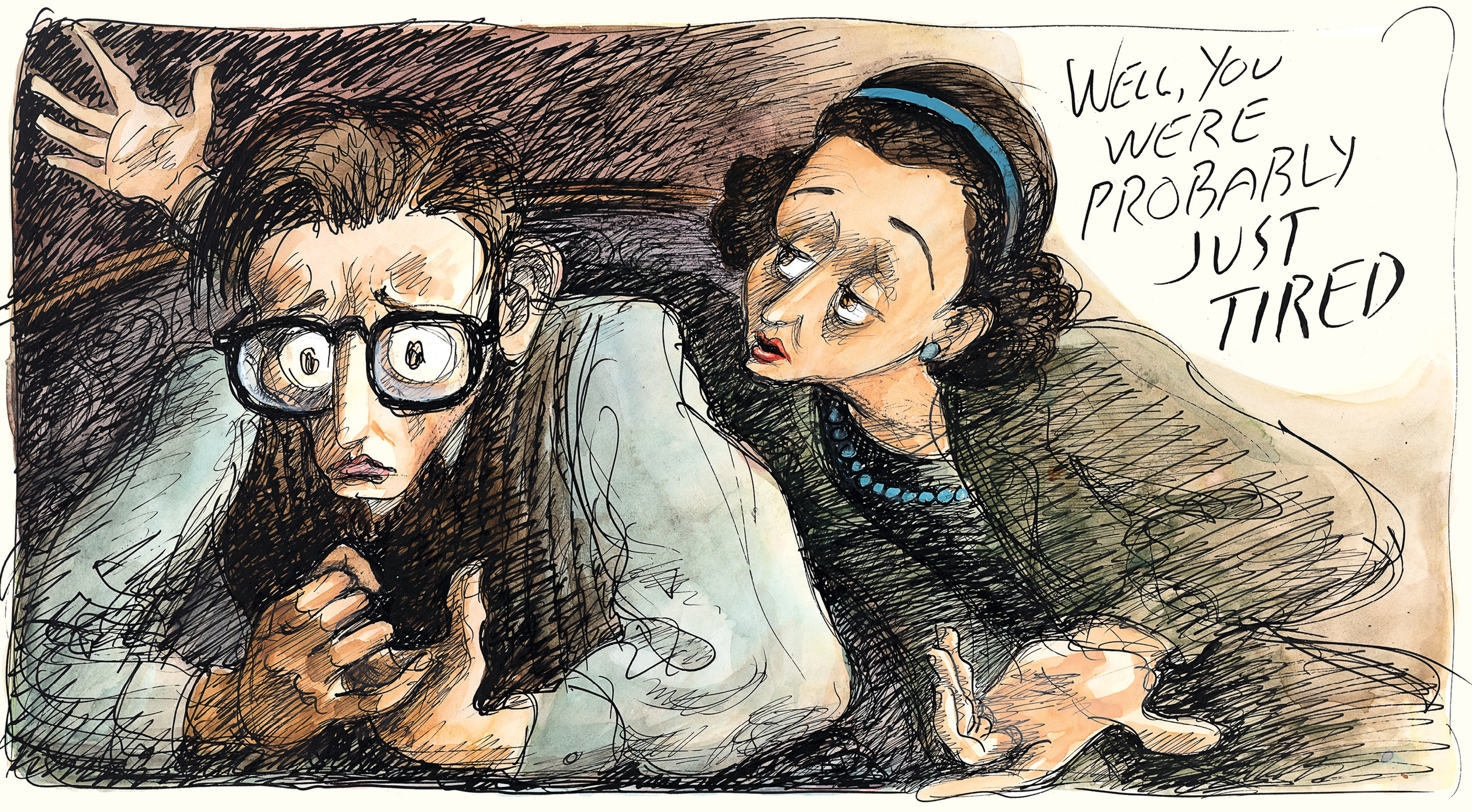

I had the good luck to have a warm, upbeat, beautiful mother who told me, when I was twelve, that I really looked better in eyeglasses, and that I was really very bright, though my teachers thought otherwise. She gave me unconditional love, and as a result I went to her with all my worries and insecurities, even when I was already a man. Heres an example. I was twenty-three, and had finally succeeded in getting a girl into bed for the first timebear in mind that this was the 1950s, not the 60sbut I had failed in that crucial rite of passage. I was distraught. I told Mom, and after giving it a moments thought, she said:

I knew from seeing those Andy Hardy movies that the proper person a son should go to when such a calamity happens was his father. But my father was no Judge Hardy, and we didnt live in a spacious Victorian house on a tree-lined street in a town called Carvel, somewhere in the Midwest. We lived in a fifth-floor walk-up in the Bronx, and there wasnt a room suitable for a man-to-man talk. Furthermore, my father, Morris Schwartz, was not a justice of the court. He was a door-to-door salesman, and far from being wise and benevolent, he was stupid, insensitive, grouchy, mean-spirited, fault-finding, and a racist. Let me also add that he made slurping sounds when he ate soup and always had cigarette ashes on his jacket.

People meeting my parents for the first time surely asked themselves, Why do you suppose she married him? I wondered the same thing. Why did tall, beautiful, Rebecca Kleinberg marry short, jug-eared Morris Schwartz? (If youre confused because my fathers surname is different from mine, I legally changed it to Sorel the momentthe secondI got a steady job.) Whatever reason Mom had for marrying him, I wished he would just somehow disappear. I clearly remember when I was eight or nine, being with him on a nearly empty subway platform, and thinking that, if only that one woman wasnt standing there, I could push him in front of the oncoming train, and no one would see me doing it. Of course, when I grew older, I realized how wrong that would have been. The motorman would have seen me.

Clearly, I was going to be stuck with him until I could find work and move out. Yet I couldnt stop myself from asking Yetta, the youngest of Moms four sisters, Why did Mom marry him? She was as flummoxed as everyone else. Even Aunt Jeanette, the college graduate in the family, who always had a Freudian explanation for everything, couldnt come up with a reason. She assured me that Papa and Mama Kleinberg had begged Rebecca not to marry him. And Mom wasnt pregnant. I was born two years after they married in 1927.

Of course, I couldnt flat out ask my mother, Why the hell did you marry him? But when I was in my teens I thought I might get a clue to the answer by asking Mom how she and Morris met. Here, pretty much, is what she told me.

I was sixteen when I heard about a job in a ladies hat factory on Houston Street. This was a few months after Mama and my sisters and I arrived in America from Romania in 1923. Papa was already here. He had come earlier and sent for us as soon as he had saved enough money to bring us over. Papa had rented a walk-up apartment for us just above the Third Avenue El in the Bronx. It was nowhere near Houston Street, so I asked Papa for carfare. He told me I was too young to work, but I insisted that I wanted to work, and so he gave me three nickels. Two were for the subway that would take me to the factory and home, and one was for lunch.