The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Theres a sepia document on the kitchen table, just out of the new babys reach. My mum brought it the last time she visited us, thinking Id be interested in her maternity records. The print on the envelope reads CONFIDENTIAL . IMPORTANT NOTE runs along the bottom: This card must be kept in YOUR POSSESSION . In the 1970s, Britains National Health Service spoke to its patients in officious tones.

The brown-beige color of the envelope is not unlike the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century manuscripts I usually read in my job as a historian. Paper often starts out almost white, but the centuries bring out the impurities by the time the sheets rest in a contemporary archive.

The NHS envelope is scuffed from use, but in good enough shape to open. On the outside, my mothers London N14 address is crossed through, replaced by the Essex address of my childhood. A small urban flat switched for a tidy three-bedroom house in a village not far from the North Sea.

Id like to remove the envelopes contents, but the baby keeps moving on my lap, locks eyes and wants distracting, smells good and distracts. Starfish hands bat toward round face, signaling the naptime hour.

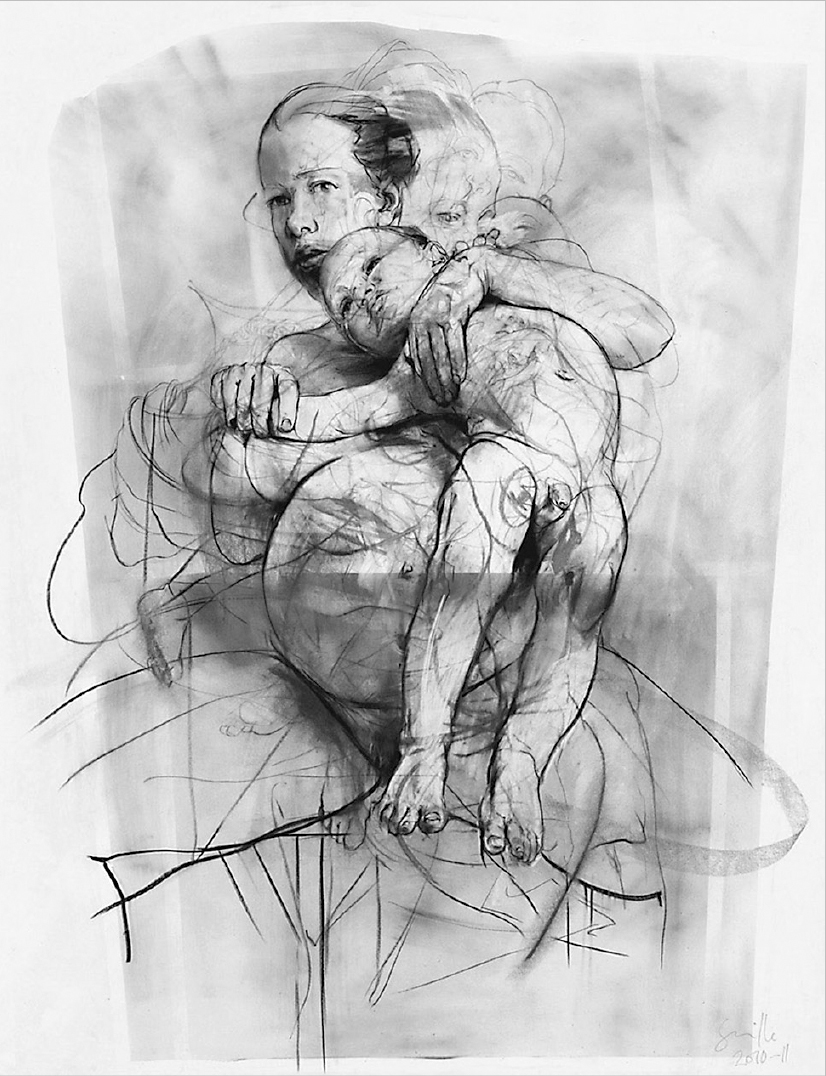

What are the many different pasts of becoming a mother? What can we know of what, say, seventeenth-century people called going with child: carrying and caring for an infant? Going with child is, as it were, a rough sea on which a big-bellied woman and her infant floats the space of nine months, reckoned an observer in 1688. Then labour, which is the only port, is so full of dangerous rocks, that very often both the one and the other, after they are arrived have yet need of much help to defend them. A stormy, shape-shifting scene, fraught and rocky, full of drama.

In an hour and a half, there will be a clatter at the front door, and my spouse, K, will arrive with the babys noisy older sibling. Better put the envelope, and its single homegrown piece of evidence, aside for now.

The baby is asleep, and slanting sunlight falls on the Mrs. printed by the envelopes first address line. The late-twentieth-century NHS presumed that pregnancy indicated marriage. The everyday phrase unwed mother shifted to the less pejorative single mother in the 1960s, but a wedding and stay-at-home motherhood were still held out as the family norm.

Inside the envelope is a Co-operation Record Card for Maternity Patients with an infants immunization record stapled on top. What insights might this hold about mothering an infant in 1970s Britain? Antenatal care began at three months, after a test administered by a doctor to confirm the pregnancy. Twelve weeks, reads the record card. Fourteen weeks, eighteen, twenty-two

Other London mothers of the same decade told the sociologist Ann Oakley about attending an prenatal clinic. Very assembly line, reckoned the twenty-six-year-old illustrator Gillian Hartley about her first visit; I got up a nervous wreck as usual, though the staff were nice. Nina Brady, a shop assistant who called Oakley dear, found the encounter with a doctor so embarrassing that she did not want to go again. Brady told one of the nurses about a woman who never attended the clinic because she thought it was all a load of rubbish. Twenty-six weeks, twenty-eight, thirty. My mother, then a shy nurse in her late twenties, attended all her appointments.

Quickening gets its own entry on the record card. The first time a person felt their baby move was deemed medically important. The term has a long pedigree. Seventeenth-century Englishwomen took quickening as definitive proof of pregnancy. Ojibwe women native to North America saw this as the moment when a life within became a human being. Familiarity with the term has come and gone. Charlotte Hirsch, a novelist who in 1917 anonymously wrote the first published personal account of being pregnant, had always thought the word meant the baby taking its first breaths of outside air. My English friends and family routinely know the term. The friends and colleagues where I usually reside and work in the United States sometimes do not.

The record card documents the sensations and feelings of pregnancy tersely and at second hand. Quickening is recorded by a date, with no other details. Well recorded the London doctor at thirty-four weeks. Feels well wrote the Essex doctor a little later. Well again, at forty. If its a dilemma figuring out how to recapture experiences from the 1970s, how much greater for the terrain of Britain and North America since the seventeenth century? These places have sometimes been connectedby a colonial past or by changes common to the Westand sometimes not.

Feels well. The brevity of that tiny phrase is typical of what past experiences of mothering have left behind for us to notice, retrospectively, and to wonder about. Even in the best-lit corners of past and present, caring for an infant interrupts thinking, punctures reflection, or leaves a book half read. The richest records, such as letters and diaries, often stop exactly as they are getting interesting. A piece of correspondence is left off, mid-sentence; the letter writer called away by a cry, or a diary suspends, because both hands are needed to hold the baby.

The political revolutions I more usually research as a historian lend themselves to massive paper trails: declarations of independence, constitutions, newspaper columns, ideological pamphlets, wartime correspondence. When not on maternity leave, I tell my students grand narratives about the late-eighteenth-century transition from kingdoms to republics. Their eyes widen at the less familiar parts: not the doings of a Benjamin Franklin or a Marie Antoinette, but enslaved men and women escaping to freedom, or Native American diplomats forging alliances with France or Spain, Britain or the United States, in an attempt to stop settlers expansion across the American continent. About mothering an infant, I am on smaller, grittier ground. The drama is piecemeal, and the record is fragmentary.

Some of quickening, or of feeling well, 1970s-style, is illuminated by contexts immediately beyond the maternity card. Pregnancy should be healthy and content, according to medical recommendations of the daya happy event.

Will it be a happy book? my very private mother asks, kindly, tentatively, on the phone, a thread of worry in her voice.

In fact, we know more about experiences of mothering in the 1970s than in any earlier generation, thanks to the womens liberation movement of that decade. When Ann Oakley asked her London interviewees about quickening, they detailed the babys first movements variously as like food resting, or just like fluttering, or a little butterfly, a fish swimmingor a very large tadpole. Some writers, mainly white feminists in the United States, published maternal memoirs, as if the fact that having a baby had become optional finally allowed the complexity of maternity to be worthy of interest. Others defiantly wrote poetry. The Language of the Brag, Sharon Olds titled her poem about giving birth.