ALSO BY THEODORE VRETTOS

NONFICTION

The Elgin Affair

A Shadow of Magnitude

FICTION

Hammer on the Sea

Origen

Lord Elgins Lady

Birds of Winter

THE FREE PRESS

A division of Simon & Schuster Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2001 by Theodore Vrettos

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

THE FREE PRESS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

For information about special discounts and bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales: 1-800-456-6798 or business@simonandschuster.com

DESIGNED BY KEVIN HANEK

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vrettos, Theodore.

Alexandria : city of the western mind / Theodore Vrettos.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

1. Alexandria (Egypt)History. 2. History, Ancient. I. Title.

DT73.A4 V73 2001 2001040891

932dc21

ISBN 0-7432-0569-3 (alk. paper)

eISBN: 978-1-451-60348-4

To the memory of Lawrence Durrell

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

IN THE Odyssey, Homer describes which they call Pharos, lying off Egypt. It has a harbor with good anchorage, and hence they put out to sea after drawing water.

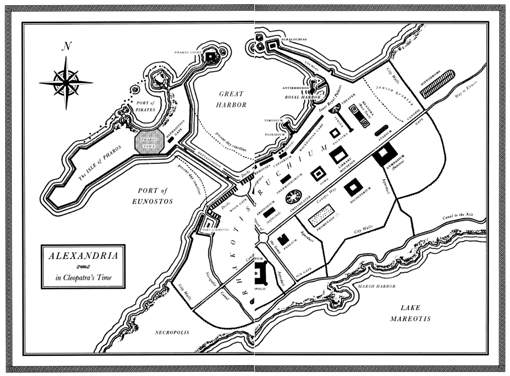

When Alexander the Great came upon this site in 332 B.C., a settlement named Rhakotis sprawled along the shore and was a haven for fishermen and pirates. Behind it, five native villages were scattered along the strip between Lake Mareotis and the Mediterranean Sea. Just off the coast lay the island of Pharos, where Alexander stayed before setting out to find the oracle of Zeus Ammon in the Siwa Oasis.

Diodorus Siculus, writing in the first century B.C., furnished detailed information about Alexanders deciding to found a great city in Egypt and issuing orders to his architects that they build the city between the marsh (Lake Mareotis) and the sea. , stated the Greek historian, laid out the site and traced the streets skillfully and ordered that the city should be called after him, Alexandria. It was conveniently situated near the harbor of Pharos, and by selecting the right angle of the streets, Alexander made the city breathe with the Etesian winds [the northwestern winds of summer], so that as these blew across a great expanse of sea, they cooled the air of the city and thus provided its inhabitants with a moderate climate and good health. Alexanders architects also laid out the walls so that they were large and very strong. Lying between the great marsh and the sea, the city thus afforded two approaches by land, both narrow and easily protected in case of war.

Since the Nile was only twenty miles away, Alexander realized that wherever this great river poured itself into the sea, so much silt and mud would collect at the Delta it would be impossible to have a sound harbor there. But at Pharos, silt posed no problem. His new city would have two clear harbors: one on the Mediterranean, the other facing Lake Mareotis to the south. Furthermore, he would construct a canal from the lake to the Nile, connecting Alexandria with all the river ports of southern Egypt. Thus the city would be able to accept trade ships from the Mediterranean as well as from the Nile without danger of being clogged by the accumulation of sediment.

Because Alexander had defeated the Persians at the Dardanelles and at Asia Minor, and because Egypt clung to its bitter hatred of the Persians, the country fell willingly into his hands. He was twenty-five when he entered Memphis, the ancient capital of Egypt (modern Cairo). From there, he traveled by barge down the Nile, all the way to the clay-bound coast facing Pharos Island. The place apparently fascinated him, and he ordered his architect Deinocrates to build a magnificent city on the site. The Greek biographer Plutarch wrote that Alexander knelt down and sliced out the streets of this proposed city with strokes of his finger in the sandstreets wide enough for eight chariots to travel side by side, each leading diagonally to the sea.

To maintain control of his newly acquired Egyptian territory, Alexander needed a capital on the coast to serve as a supply link with Macedonia. At Pharos, he had found the ideal site: secure harbor, mild climate, with ample fresh water, and easy access to the Nile and the Lower Kingdom. Alexander hoped that the genius of Hellenism would be perpetuated here, a metropolis of culture to benefit the entire world.

When Alexander departed for the Siwa Oasis, Deinocrates, a renowned architect of the time, carried out Alexanders instructions, laying out the new capital of Egypt: crossing the streets at right angles and lining them on both sides with columns the full length of the city, east to west. Along with spacious parks and gardens, slaves constructed lavish buildings and palaces, including a university called the Mouseion (home of the Muses), and a magnificent library, which would attract the best scientists, philosophers, mathematicians, physicians, teachers, and scholars of the age.

Amazingly, Alexanders grand dream would find its way into the mind and soul of the city, and produce a profound influence on western culture, art, politics, and religion to this day.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I AM GRATEFUL TO Dr. Hassan I. Ismail, curator of the GrecoRoman Museum in Alexandria, for his cooperation and help. I am also indebted to Dr. Djanane Batanouni of Alexandria for her assistance in tracking down elusive documents, manuscripts, and maps of ancient Alexandria.

I received invaluable support and encouragement from John Updike, from my esteemed fellow Joyceans, and from Dr. Francis Blessington of Northeastern University.

Many libraries and museums throughout the world offered necessary information and material. Among these are Harvard Universitys Widener Library, the Vatican Museums in Rome, the Archbishop Iakovos Library and Learning Resource Center at Hellenic College in Brookline, Massachusetts, the Harvard Divinity School Library, the Archeological Museum of Pella in Macedonia, the National Archeological Museum of Naples, the National Gallery of Art and the Library of Congress in Washington, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Boston Public Library, the Goddard Library of the Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Hamilton, Massachusetts, and the Peabody Institute Library in Danvers, Massachusetts, particularly its competent researchers: Nick McAuliffe, Suzanne MacLeod, and Donna Maturi.

I owe utmost thanks to my astute editor, Stephen Morrow, at THE FREE PRESS, also to his assistant Beth Haymaker for her support, and to Fred Wiemer, for his excellent copyediting of the manuscript. My most sincere thanks are reserved for my agent, John Taylor Ike Williams, for nurturing the book with his many valuable suggestions and for his devoted work throughout.