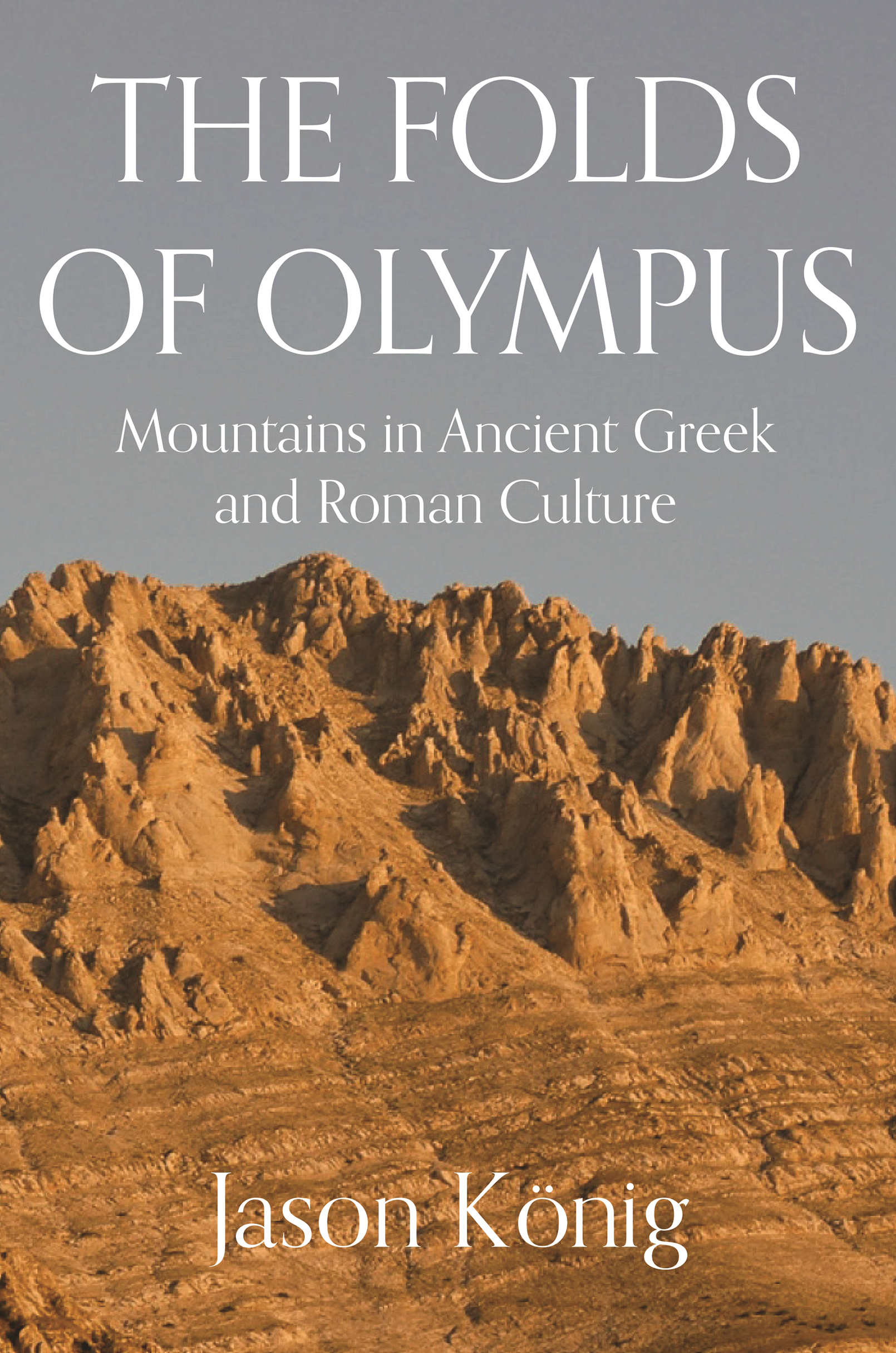

THE FOLDS OF OLYMPUS

The Folds of Olympus

MOUNTAINS IN ANCIENT GREEK AND ROMAN CULTURE

JASON KNIG

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2022 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Control Number 2022934720

ISBN 978-0-691-20129-0

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-23849-4

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Ben Tate and Josh Drake

Production Editorial: Jill Harris

Jacket Design: Kimberly Castaeda

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: Alyssa Sanford and Charlotte Coyne

Copyeditor: Jennifer Harris

Jacket image: Jason Knig

For Eliza, Rory, and Serena

CONTENTS

- xi

- xiv

- xvii

- xxix

ILLUSTRATIONS

- Ruined columns from the temple of Zeus Lykaios, with the summit of Mount Lykaion behind.

- View from the summit of Mount Lykaion looking northeast towards the stadium and hippodrome.

- View south from the summit of Mount Ithome over ancient Messene.

- Mount Apesas with its flat top from the stadium at Nemea.

- View from the summit of Mount Arachnaion, looking west to Argos.

- View to the west from the summit of Zagaras, easternmost peak of the Helikon range.

- Mytikas summit, Mount Olympus.

- Summit ridge of Mount Kithairon.

- Hippokrene spring, Zagaras, Mount Helikon.

- Moses receiving the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. Mosaic from the Basilica, Saint Catherines Monastery, Sinai, sixth century CE.

- Prometheus bound to a rocky arch, being freed by Herakles. Apulian calyx-krater, ca 340s BCE, attributed to the Branca Painter. Berlin, Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

- Muse sitting on the rocks of Mount Helikon. White-ground lekythos, ca 445435 BCE, attributed to the Achilles Painter. Munich, Staatliche Antikensammlungen, SCH 80 (formerly Lugano, Schoen Collection).

- The Judgement of Paris. Red-figured hydria, ca 470 BCE. London, British Museum.

- The Judgement of Paris. Terracotta pyxis, attributed to the Penthesilea Painter, ca 465460 BCE. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Silver stater, Arkadian League, 363362 BCE. Reverse: Pan sitting on rocks. Berlin, Mnzkabinett der Staatlichen Museum, Altes Museum.

- Coin showing head of Vespasian (obverse); Roma seated on the seven hills (reverse), 71 CE. London, British Museum.

- Trajans Column, Rome, completed 113 CE. Scene LXII: Roman forces advancing through forested, mountainous scenery.

- Wall painting of a villa with mountains, from the House of Lucretius Fronto, Pompeii; detail of the south wall of the tablinum, first century CE. DeAgostini Picture Library / Scala, Florence.

- Narcissus at the fountain, from the House of Lucretius Fronto, Pompeii, bedroom, first century CE. Photo Scala, Florence / Luciano Romano.

- Nineteenth-century watercolour of a wall painting from Pompeii showing the Rape of Hylas, from the House of Virnius Modestus, IX.7.16, early first century CE(?). DAI-Rom, Archivio, A-VII-33-088.

- Wall painting showing Odysseus companions in the land of the Laestrygonians, from a house in the via Graziosa, Rome, mid-first century BCE. Musei Vaticani.

- Bacchus and Mount Vesuvius, Lararium of the House of the Centenary, Pompeii, first century CE. Naples Archaeological Museum.

- Euthykles Stele. Found in the Valley of the Muses, late-third century BCE. Height 1.19 m, width 0.50 m. National Archaeological Museum, Athens, NAM 1455.

- Marble relief showing the apotheosis of Homer, Archelaos of Priene, from Bovillae, second century BCE(?). Height 1.15 m. London, British Museum.

- Route of the Persian outflanking move at the battle of Thermopylai, Mount Kallidromos, looking west towards Eleftherochori from above Nevropoli.

- Peutinger Table, section 5: Dalmatia, Pannonia, Moesia, Campania, Apulia, Africa.

- Coin showing the head of Julia Maesa, grandmother of the emperors Elagabalus and Severus Alexander (obverse), and Mount Argaios (reverse), 221224 CE. Caesarea, Cappadocia.

This map includes some of the most important mountains, mountain ranges, and regions discussed in the book, but it is not intended to be exhaustive. For more detailed mapping, see Talbert (2000).

PREFACE

IF YOU WANT to see how mountains mattered in ancient Greece, there is nowhere better than Mount Lykaion in Arkadia. I went there with my family one morning late in May in 2014. We drove most of the way up, past the village of Ano Karyes, to the stadium and hippodrome a couple of hundred metres below the southern peak, slightly the lower of the mountains two summits. I went up from there on foot while the others stayed down below; they were on the lookout for snakes, having tripped over one in the fort at Acrocorinth the day before. A track curves upwards around the west side of the mountain. The slopes were green and covered with late-spring flowers. Just below the summit you come to a wide plateau; then you go up a steep conical mound to the top. Its hard not to be distracted by the view. You get an amazing sense of height. The southern peak is at 1,382 metresnot much by Greek standards, but it stands high up above the industrialised plain of Megalopolis with its giant smoking chimneys. And then beyond that you can see the ripples of other mountains on all sides far into the distance, with the snow-covered summit of Mount Taygetos through the haze away to the south, and Mount Ithome, and the temple of Apollo at Bassai covered in its protective tent to the west.

But it was the summit itself that I had come to see. The top section of it (about the top metre and a half above the bedrock) is the remains of the ash altar of Zeus Lykaios. It was one of many altars on mountain summits across the Mediterranean world. But this one is special, in part because it has been excavated more extensively than any equivalent site. There was not a vast amount to see when I went there, outside the excavation season: some shallow trenches, covered over with plastic sheeting, and overgrown with grass. And yet the contents of those trenches can help us to draw a remarkably rich portrait of the way in which the summit was used by the areas inhabitants. Initial excavations over 100 years ago uncovered in the fabric of the altar (among other things) lots of burnt animal bones, hundreds of fragments of fifth- and fourth-century BCE pottery, and also various metal objects used as dedications, including two coins, a knife, and two miniature bronze tripod cauldrons dating from the eighth or seventh century BCE. The most recent excavations (since 2004) have turned up more animal bones, in enormous numbers (nearly all of them burnt; mainly femurs, patellas, and tails from sheep and goats, with small numbers of pig bones in addition). It is clear now that the fill of the altar site is largely made up of bone fragments. These burnt remains date from as early as 1600 BCE. Also found were thirty-three more coins, dating from the sixth to fourth century BCE, from right across mainland Greece; more tripods (roughly forty in total); and other dedications too, including a small bronze hand, holding a silver lightning bolt, broken from a statuette (the hand of Zeus, presumably), eleven lead wreaths from the seventh century BCE, and a glass-like substance called fulgurite which is formed when lightning strikes sand or soil. It is not clear whether this was brought to the altar as a dedication, the product of Zeuss lightning returned to its source in his honour, or whether it was formed by a lightning strike on the mountain itself, a reminder of the presence of the god at his sanctuary. The excavations also found some human and animal figurines in terracotta, and the remains of hundreds of Mycenean drinking vessels (ca 16001100 BCE), which suggest that the site was a place of feasting, and even, unexpectedly, a considerable number of pottery fragments dating from the final Neolithic period (ca 45003200 BC). Most astonishing of all is the recent find of a human body buried within the altar: the remains of a teenage boy with the upper part of his skull missing, dating from the eleventh century BCE. Whether that gives us evidence to back up the rumours of human sacrifice at the site that we find in a number of ancient texts