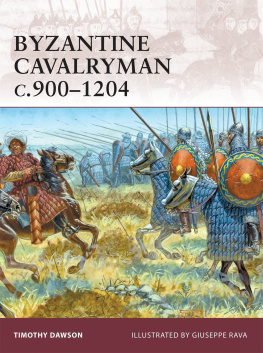

WARRIOR 139

BYZANTINE CAVALRYMAN

c. 900-1204

TIMOTHY DAWSON ILLUSTRATED BY GIUSEPPE RAVA

Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic

CONTENTS

BYZANTINE CAVALRYMAN

c. 900-1204

INTRODUCTION

C ONSULT A DICTIONARY AND under 'Byzantine' you will find it described as an adjective meaning something like 'complex, inflexible or underhand'. What should we make, therefore, of the suggestion that there was such a thing as the 'Byzantine Empire'. The answer to that lies in where and by whom the term originated. It first appears in print in 1557 from the pen of a German, Hieronymus Wolf. In the tenth century Germany had looked to Byzantium (medieval Greek Vyzantion) as a paradigm of power and opulence seeking patronage and royal marriages from the City of Vyzantion. In the twelfth century their ambitions became much more grandiose, and led to formation of what they called the 'Holy Roman Empire' claiming the inheritance of the glory days of Old Rome. To take an inheritance, however, the ancestor must be dead, and the survival of the Roman Empire in the East was somewhat problematic. At first, the ideological expedient was to claim that with the schism between the Roman and Orthodox churches and supposed decadence, the Roman Empire was morally dead, despite its semblance of sometimes robust life. Wolf's expedient went further, by attempting to deny the empire's existence stripping it of its very name. He could only do that from his place after the final fall, for during its life, its people held to their true Roman heritage with all due tenacity, as some Greek speakers have done into modern times. From as early as the first century ad the empire's residents called it 'Rmania'. The adjectives for that were Rmaikos and Rmios, and to this day, descendants of the Greek-speaking population which had continued in Ionia, the portion of Anatolia bordering the Aegean Sea, who were expelled by the Turks in the early twentieth century, still call themselves 'Rmiosi'. So what is 'Byzantine'? Properly used, it should refer to anything pertaining to the City of Vyzantion, and that is the manner in which it will be used in this volume.

Historical background

The sack of the city of Rome in the fifth century happened largely because Old Rome and the western provinces had increasingly become seen as no longer at the core of the political and economic life of the empire since Constantine I designated an ancient Greek city in Thrace as the new capital in 330 AD, and renamed it the City of Constantine (Knstantinopolis). The rulers of the Roman Empire were never content to wave the West goodbye. Roman forces fought to recover and hold Italy for the empire with varying degrees of success right through to the late twelfth century. The most determined and successful effort to recover imperial territory was under Justinian I (528-65). From the late sixth century to the end of the ninth century the concerns of the rulers were rather more pressing and closer to home. After Justinian, the ancient rivalry with Persia dominated military matters until it was conclusively settled with the destruction of the Sassanian Empire by Emperor Herakleios in 629. Along the way one of the most important monuments of Roman military literature was created around 602, the Stratgikon, sometimes attributed to the emperor and successful general Maurikios. The Stratgikon was to remain influential right through the middle Byzantine period. The rejoicing was short lived, however, as a new wave of northern barbarians culminated in the Avars besieging the capital itself in 628. The fourth-century walls were more than enough to deter them, although the residents of Knstantinopolis themselves were of the opinion that the Virgin Mary, whose likeness had been paraded about the walls, deserved the credit. At about the same time a much more serious threat arose in the East with the advent of Islam. These newly proselytized Warriors of God conquered the southern and eastern provinces in a remarkably short time. It is commonly accepted that resistance in these areas was undermined by widespread disaffection prompted by religious policies emanating from Constantinople, which had tried to impose centralized Orthodoxy on a region that had very diverse traditions of Christianity, as well as substantial enclaves of older religions. Muslim successes led to them mounting repeated sieges of the city between 668 and 677. Again, the walls of Theodosios were more than equal to the task, but could not have remained so indefinitely against continuing assaults. This prospect was forestalled by the schism in Islam and ensuing civil war that created the division between Sunni and Shi'a, and ended the first Muslim expansion into Anatolia.

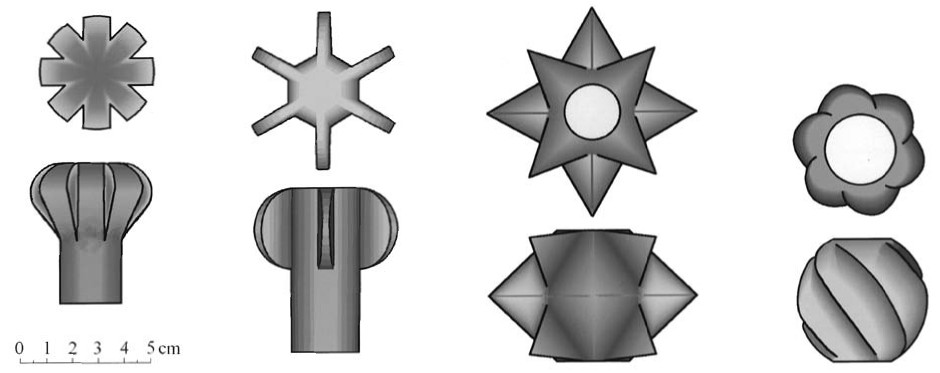

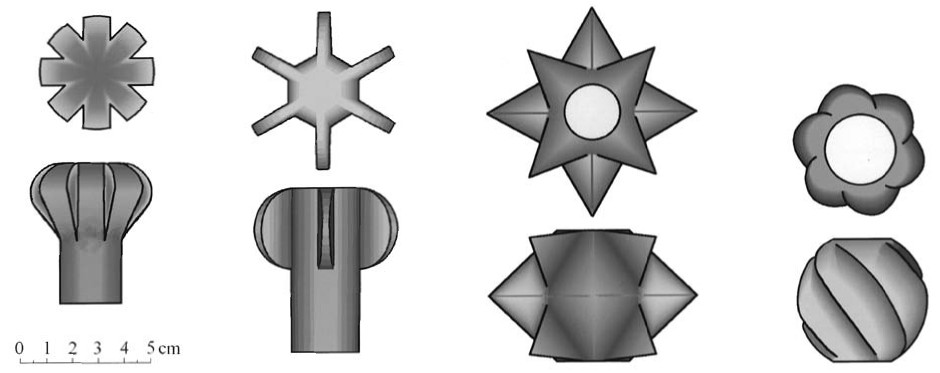

Assorted middle Byzantine era mace heads found in the Balkans. All are represented to a common scale. The material of the majority of surviving examples are iron, but there are rare bronze ones too. Besides the shapes shown here, there are multi-spiked globular examples corroborating pictures in manuscripts. These were evidently fitted with wooden shafts.

No sooner had stable borders been established with Islam than the empire was racked internally by an argument over whether the use of religious icons constituted idolatry. The seriousness with which Eastern Orthodoxy of the time took such religious debates, and the fact that the emperor had a crucial role at the centre of the church, meant that for a century the empire was violently divided against itself, body and soul. At the end of the ninth century the issue was resolved in favour of icons, and a period of stability and restoration ensued under the Macedonian emperors.

Emperor Leo VI reformed the legal system. More significantly for our interest, he revived the study of military science at the highest levels. It is evident, despite the disruptions of the preceding century, that the development of new military techniques and adaptation to new circumstances had continued. Leo's contribution was to have these recorded and codified for the first time since the Stratgikon. Leo's Taktika preserves those portions of the Stratgikon that were till relevant, and adds the new developments, including the first mention of lamellar armour. Leo was succeeded by his son, Knstantinos VII 'Born in the Purple' (Porphyrogenntos). Knstantinos Porphyrogenntos continued his father's literary activities, but on the military side his contribution is confined to a manual on imperial participation in military expeditions, which tells us much about the imperial encampment and arrangements, but nothing about ordinary soldiery.

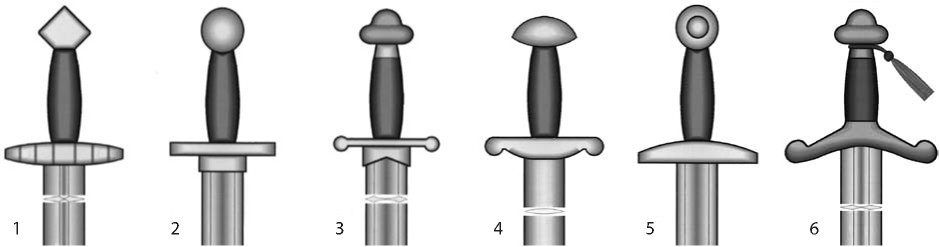

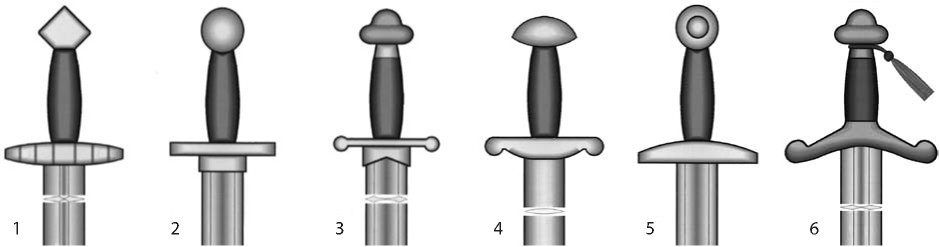

A far-from-comprehensive sample of sword fittings shown in pictorial sources. 1: tenth century (ivory triptych, Hermitage). 2-5: early eleventh century (Menologion of Basil II). 6: later eleventh century (Dafn Monastery, Chios). Blade forms include pillow section (4) and fullered with grooves ranging from narrow (1), medium (6) to broad (2, 3, 5). (2) and (3) have sleeves which encircle the mouth of the scabbard when sheathed. Other eleventh-century pictures also show what may be either a tassel or lanyard attached to the pommel (6) or at the join between grip and pommel.