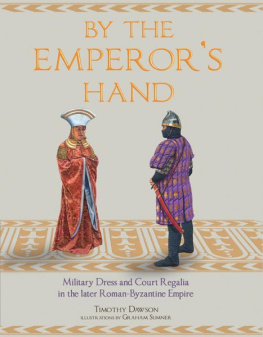

BY THE EMPERORS HAND

This edition published in 2015 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Text Timothy Dawson, 2015

Colour illustrations Graham Sumner, 2015

The right of Timothy Dawson and Graham Sumner to be identified as the creators of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-589-0

PDF ISBN: 978-1-84832-464-0

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84832-463-3

PRC ISBN: 978-1-84832-462-6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please visit

or write to us at the above address.

Designed by David Rose

Printed and bound in Malta by Gutenberg Press Ltd

CONTENTS

PLATES

Between pages 66 and 67

INTRODUCTION

T he study of the clothing of Rmania, or the Enduring Roman (or Byzantine) Empire, is an area which has been under-explored to date in serious scholarship. Even in the area of court dress and regalia, for which there is a great deal more reliable source material than for the garb of common folk, the amount of study to date is quite scant. Much of the material that does exist on the subject is quite antiquated and all of it leaves a great deal of room for refinement.

The purpose of this volume is to trace as accurately as possible the evolution of clothing around the court and in the military from the sixth century to the end of the empire in 1453. Crucial to tracing this evolution will be the task of identifying wherever possible the precise form and defining characteristics of garments mentioned and depicted in the sources, for it is only with such clear identifications that changes in terminology can be distinguished from changes in the form of the physical items of dress, or changes in the manner of artistic representation. The principal sources will be in the first instance literary, corroborated where possible by pictures. The old paradigm which suggested that the art of Byzantion was unrelievedly formulaic Suitable middle and late Byzantine archaeological remains are scarce, but will make an indispensable contribution to the study, as will comparative material from Islamic and European realms. Other important inputs to this work are those of practical knowledge and practical application. The great majority of previous studies touching upon dress history in general, let alone that of Byzantion, even in the more popular realm, have manifestly been undertaken with little or no hands-on experience of the construction of clothing, and this has often led authors down blind alleys. Prior practical knowledge of this type proves to be especially invaluable in interpreting pictorial sources. In certain cases physical reconstruction has also proven to be very useful in testing and illustrating conclusions based upon academically conventional types of source material.

What will generally not be examined in much detail is the ritual and social significance of garments and ensembles. This is simply because the significance of formal court regalia is necessarily overt it exists to advertise status in a specific and readily recognisable manner. There will, however, be some cases where there is an interrelation between the identity and nature of a garment and a signification projected across rank divisions, and then it will be discussed. Another caveat is that it is impossible to discuss all the permutations of garment, ensemble and use recorded in the sources.

A further area largely untouched here is that of religious regalia and vestments. This is not because I regard it as unimportant, nor because it is unconnected with the secular regalia, but rather because it merits dedicated study of its own.

Clothing is often highly expressive, whether its wearers intend it to be or not. It can convey indications of gender, ethnicity, social class and status, occupation, identification with a subculture or, indeed, voluntary detachment from dominant social norms. The purpose of regalia is to make certain aspects of such expressiveness explicit, advertising rank and establishing a framework for the ritualistic enactment and validation of dominant social structures and the ideologies that underpin them. An essential characteristic of regalia is that it must differ from everyday dress and accessories in formally defined ways. The medieval Greek term used to denote regalia in our largest source, allaxima, embodies this, expressing the meaning of having been transformed from what commonly is. This conceptual framework is fundamental to interpreting terminology that may use words which are also applied to more mundane situations and items.

THE PRINCIPAL LITERARY SOURCES

On the civilian side, the parameters of this study are based primarily upon three comparable works. The earliest is On Powers or the Magistracies of the Roman State written by the sixth-century courtier and literateur John Lydos. The second is a composite source comprising the brief so-called Kltrologion of Filotheos, and the encyclopaedic Book of Ceremonies which was based upon it. The latest is the Treatise on the Offices falsely attributed to Kodinos. These works are of a type called taktikon which originated in the Later Roman Empire, and were devoted to recording and systematising the hierarchy of the court. More will be said about the nature of each of the works at the beginning of the chapters based upon them.

Another outstanding source for this project is the Oneirokritikon (Dream interpretation manual) of Achmet ben Sirin, believed to have been written in the tenth century. The importance of clothing in this social context is reflected by the large number of scenarios given in the work which hinge upon clothing. The exceptional value of many of these is that not only does the author give garment terminology, some of it unattested elsewhere, but the nature of the items discussed and their use and behaviour is often essential to the message to be drawn from the dream, and therefore the descriptions give unique insights into the character of the dress elements discussed.

It might well be said that the Roman Empire was not merely created and sustained by its military but defined by it. In keeping with this, it developed a rich tradition of military literature early in its history. There are military manuals attributed to the sixth century, but they contain little detail of use in this project.

Since I embarked upon this project there has been one development which was of some help to me, and will be a great boon to many readers. It is an English translation of the Book of Ceremonies painstakingly prepared by Ann Moffat of the Australian National University. While my own theories and conclusions necessarily go beyond the established scholarship she could draw upon, I heartily recommend the work to anyone interested in the subject.

The limitations of the literary sources

Byzantine literary sources give us a copious terminology for clothing, but much more rarely do they give a clear indication of the nature of the item involved. This must often be deduced from subtle hints, gleaned sometimes from disparate sources, and sometimes corroborated by depiction in graphic arts. The very subtlety of such hints make interpretation, or even identification, of garments and accessories difficult, and often demands that some other bases of knowledge are needed to assist in illuminating them. Therein lie techniques which have as yet not been brought to bear to any great degree in this field. Previous scholars have certainly been highly knowledgeable in matters literary and artistic, and have done a great deal to elucidate matters in those disciplines. Yet, corroboration between the literary and artistic fields has often not been pursued as systematically as it might, and further significant advances can be made by forging links between the disciplines of textile history, the more embryonic field of costume history, and practical experience of textile craft.

Next page