SCOTTISH NATIONAL

DRESS AND TARTAN

Stuart Reid

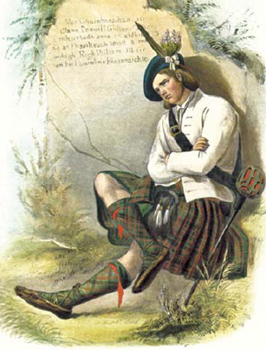

A MacDonald of Glencoe by Robert McIan, wears a plain white jacket, which allows the tartan to stand out very effectively. The historical provenance may be dubious but similar white drill jackets were very popular in Queen Victorias Highland regiments.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

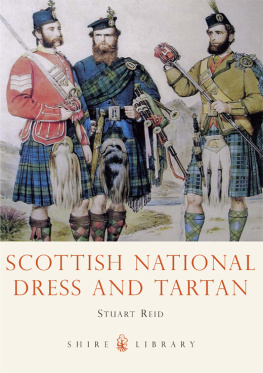

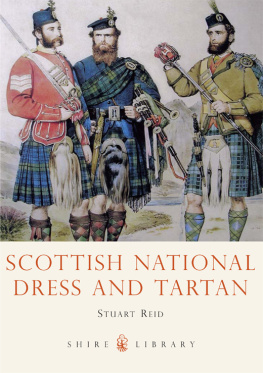

The style of the uniforms worn by these pipers of the Highland Light Infantry can be seen today on many of the larger pipe bands.

CONTENTS

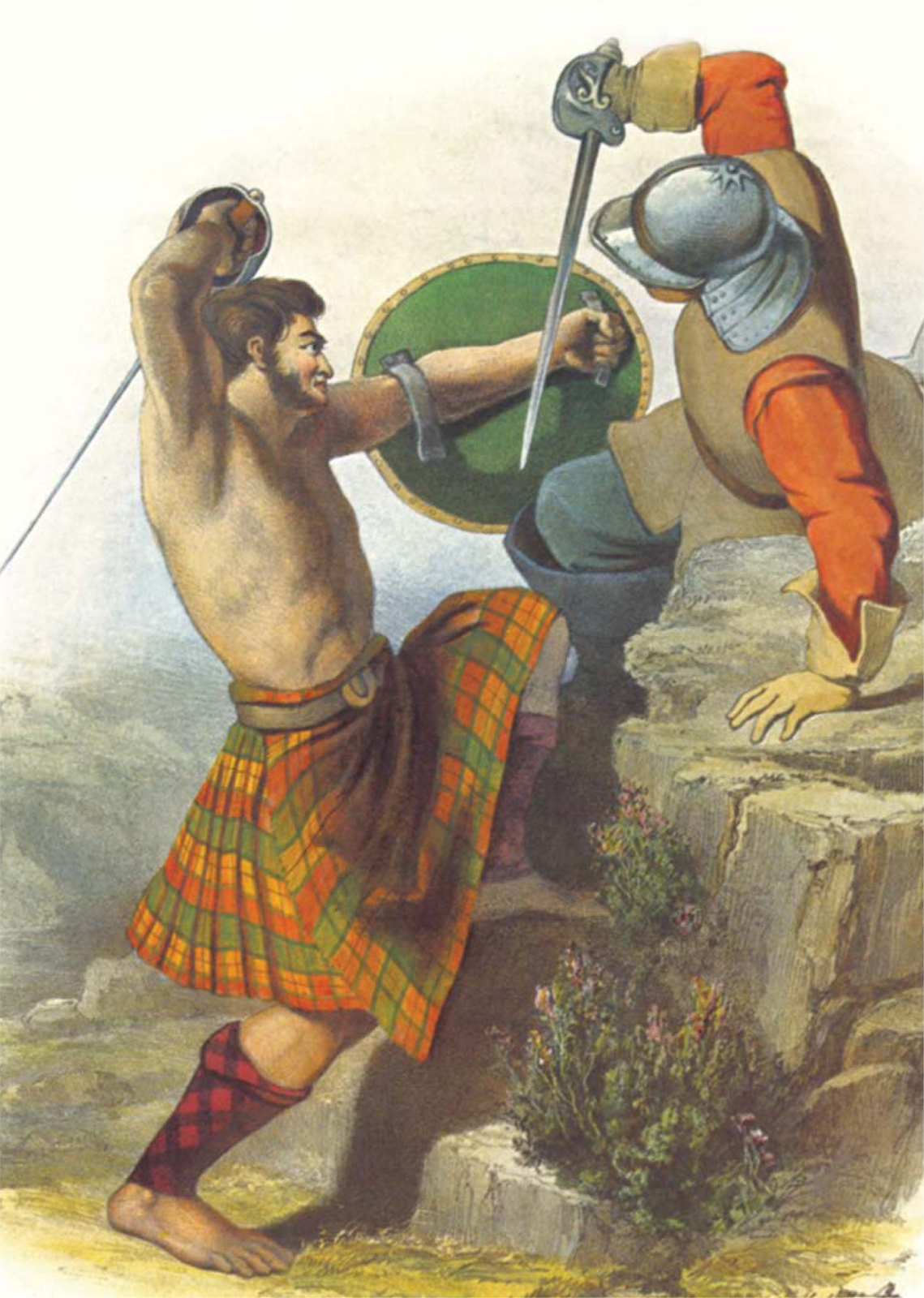

Victorian romanticism personified in all its anachronistic glory, depicted by Robert McIan in his celebrated Costumes of the Clans (1843).

SCOTLANDS NATIONAL DRESS

T HE KILT and the tartan are not only Scotlands national dress, but unquestionably form the most distinctive and most widely recognised national dress in the world. Strictly speaking the kilt began as a form of Highland dress and is often believed to belong only to that part of Scotland. Yet, while for a time this might arguably have been true, its claim to be the legitimate national dress for all Scots has a very substantial foundation.

Scottish dress shares many cultural similarities with folk dress elsewhere in the world insofar as what was once ordinary working clothing has over the years been formalised and embellished to turn it into a ceremonial dress suitable for high days and holy days. In that respect it is no different from German lederhosen or Texan cowboy shirts and blue jeans, for example. In short, it is an outward expression of the wearers historical and cultural identity and its very distinctiveness encouraged its adoption as a symbol of not just Highland but Scottish identity a surprisingly long time ago.

In popular myth there is something called the Highland Line, identified with the great geological fault slashing diagonally across Scotland from Dumbarton Rock on the River Clyde to Dunottar Castle on the East Coast just below Aberdeen. Those living to the north of this line are held to be the true Highlanders, the original wearers of the kilt and tartans, while those to the south of it are Lowlanders blessed with only the most tenuous entitlement to wear the tartan and none at all to wear the kilt. In reality history is rarely so simple.

Before the Wars of Independence culminating in Robert the Bruces great victory at Bannockburn in 1314, there is little evidence of such a split. There were rugged parts of Scotland and less rugged parts of Scotland, but neither the English kings who coveted it nor the Scottish kings who defended it ever regarded it as two parallel but different realms.

When King Alexander III tumbled over a cliff in 1286, leaving no obvious heir, the various claimants to the empty throne appealed to Edward I of England for arbitration. Edward duly judged the case honestly in favour of John Balliol, but also took the opportunity to declare himself Scotlands feudal overlord. The Scots were unimpressed and refused to be intimidated, but it took nearly twenty years of bloody warfare to settle the matter. Sadly, for much of that time the English were the least of the Bruces worries. Before he could lead the Scots army to victory at Bannockburn he first had to fight and win a vicious civil war against the many supporters of the Balliols, chiefly led by the Comyns (or Cummings) in the North and the MacDougalls in the West.

Their lands, as it happened, stretched in a great arc from Lorne through Lochaber, Moray and Badenoch to the Buchan coast of the North East, and so included most of what would later become considered as the Highlands. Thus the eclipse of the Comyn lords of Lochaber and Badenoch effectively disenfranchised the Highlands in a Scotland thereafter dominated by the Bruces and their Stewart successors.

At the same time the growing commercial importance of the thriving East Coast ports meant that the hinterland (the Highlands) lacking both economic and political clout, steadily became marginalised so that by the seventeenth century there was indeed a Highland line, of sorts. It was always nevertheless a very indeterminate line and it is instructive to note that when the very last Scots Army was raised in 1745 the regiments of the Athole Brigade raised from amongst the Perthshire glens, the Gordons from Strathbogie and Strathdon, and the Farquharsons from Deeside were considered not as Highlanders but as part of the Lowland Division.

This elegant Highland gentleman of the seventeenth century in another painting by McIan may look unlikely, but is rather less flamboyantly dressed than a contemporary portrait of Sir Mungo Murray by John Michael Wright.

It was a similar story with language and if Scots, a tongue in some ways more akin to Flemish and German than to English, became predominant in the east-coast towns, it was still a different matter in the countryside and a form of Gaelic (Buchan Gaelic) was still being spoken alongside Doric in the supposedly lowland North East in the memory of the authors grandparents!

The use of the plaid by the common people was still ubiquitous all over Scotland when the political landscape changed completely in 1707. In that year, by a mixture of blackmail, bribery and outright coercion England, desperate for Scottish soldiers to maintain a bloody and ruinously expensive war against France, forced through an act of Union; henceforth Scotland would be ruled from Westminster rather than Edinburgh. However, although the Scots Parliament reluctantly acquiesced in its own dissolution it was a deeply unpopular move in the country at large. Scotland was now proclaimed to be North Britain and in response its people turned to ostentatiously displaying the tartan as a defiant affirmation of their Scottish identity.

A reasonably convincing interpretation by McIan of a Highland piper wearing a conventional mid-seventeenth-century doublet.

This was most conspicuously seen during the last Jacobite Rising in 1745. When Bonnie Prince Charlie landed in the West Highlands, his first followers were, naturally enough, Highland clansmen, but by the time his army left Edinburgh on the famous march to Derby at least half of them were Lowland Scots. Nevertheless most wore Highland clothes, spelled out in an edict by Lord Lewis Gordon, the rebel commander in the North East of Scotland, requiring recruits to be well cloathed, with short cloathes, plaid, new shoes, and three pair of hose. Other Jacobite officers enthusiastically followed suit and even the cavalry had tartan jackets or at the very least tartan scarves or tartan-mounted shoulder belts.

Next page