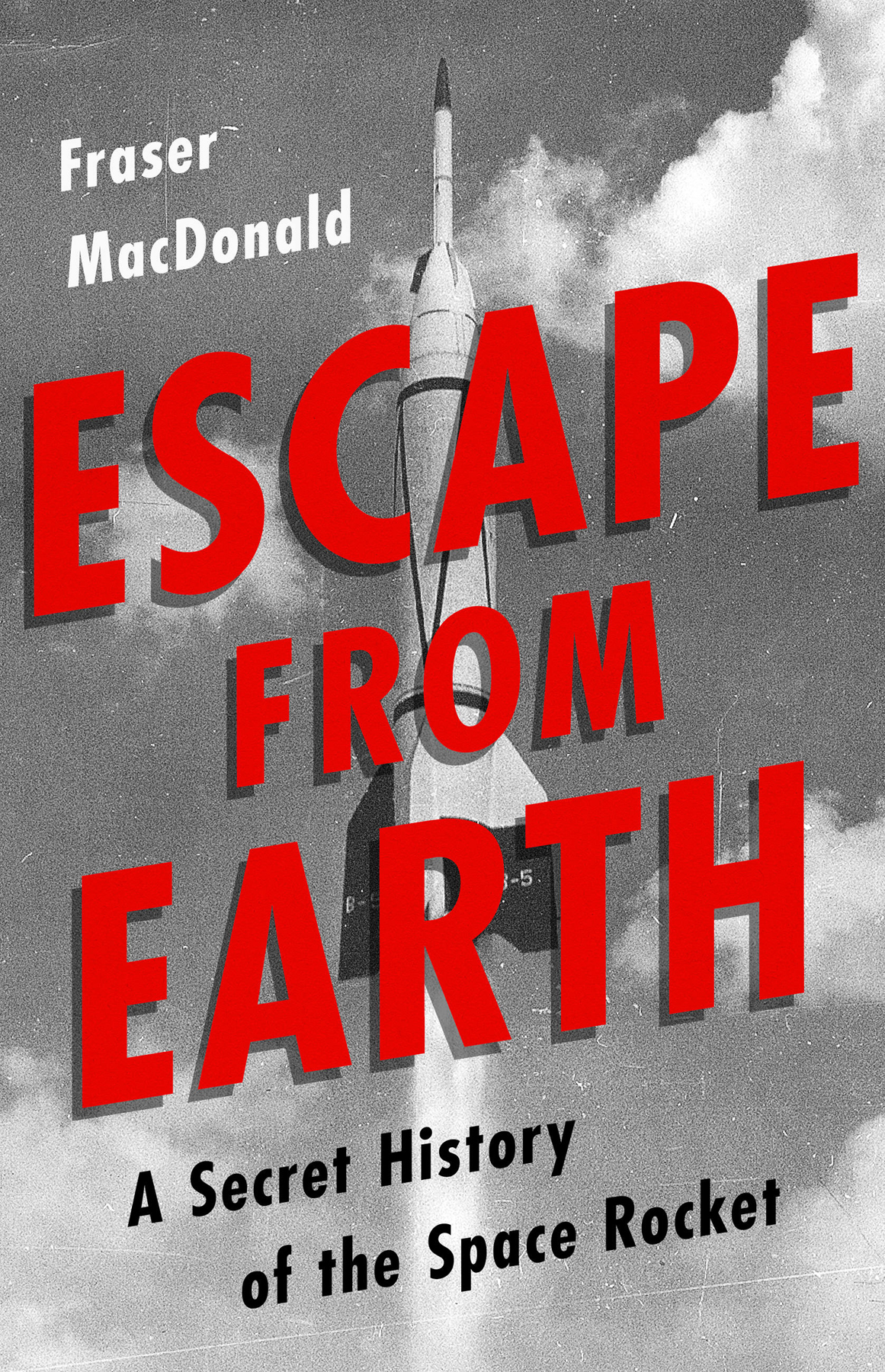

Copyright 2019 by Fraser MacDonald

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover image: National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Profile Books Ltd.

First US Edition: June 2019

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019936734

ISBNs: 978-1-61039-871-8 (hardcover), 978-1-61039-869-5 (ebook)

E3-20190514-JV-NF-ORI

For Roger Bacon

There is something addictive about secrets.

J. Edgar Hoover

SPACE FLIGHT MAY SEEM like a transcendent themethe stuff of soaring visions and azure skiesbut its history is grounded in the dirt. This book is the unearthing.

It is a story that Ive reconstructed from archives buried in obscure places. Perhaps thats why the research has so often felt like an exhumation. Its not just that the principal characters in this book are dead, which they are, but that their reputations have followed them down to the grave. This is about people who have, for the most part, been forgotten, even though their lives are central to the achievements of the twentieth century. I only found out about them through an accident of geography.

In the closing years of the twentieth century, I was conducting some doctoral fieldwork on the island of North Uist, in Scotlands Outer Hebrides. I didnt go there to study rockets but my interest in the cultural landscape made me curious about the one place on the island to which I was denied access: a hilltop called Cleatrabhal, hill of the ridge in Old Norse. Its militarised summit gives a commanding view over the irregular carpet of moor and loch; there are even traces of Neolithic and Iron Age communities. But its the Cold War infrastructure that still dominates Cleatrabhal, and it was there that I first started to dig into the story of the Space Age.

I learned that this site had been part of a rocket testing range built on the neighbouring island of South Uist in the late 1950s. The next time I was down in London, I dredged the National Archives to find declassified military files about the planning of the range. I discovered that it had been built to test a type of American rocket. And not just any rocket: the Corporal was the first guided missile authorised to carry a nuclear warhead. To my mild shame, I had never heard of it.

I wrote a few dry academic papers about missile testing and Cold War geopolitics, but the origins of this technology remained a bit hazy. I knew that the Corporal had been designed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and I knew, too, that JPL was at the forefront of space exploration today. But I thought it a bit odd that the key engineer behind both the rocket and the laboratory should be such a distant figure. His name was Frank J. Malina.

In 2006, I noticed a new Wikipedia article about Malinaa one-sentence entry that described him as an aeronautical engineer and painter. Ploughing through a few books and oral histories turned up more information. I read that when he was little more than a graduate student, with the help of friends whose credentials were even less impressive than his own, he developed the first US rocket to reach an extreme altitude. Its called the WAC Corporal, the precursor to the Corporal. These days rocket science is a clich for complexity, a shorthand for engineering brilliance. In the 1930s, however, the opposite was the case: rocketry was so discredited that it didnt belong anywhere near the word science. Yet it was Frank Malina, arguably more than anyone else in the United States, who made it respectable. Why then was his name absent from histories of space flight? There were rumours about his politics, and even more outlandish stories about his colleagues.

Years passed. I was invited to give a paper at the International Astronautical Congress, where by chance I ran into the astronomer Roger Malina, Franks son. I had no particular plans to write about his father but I was intrigued by why he wasnt better known. Why did he walk away from practical rocketry? Why did he leave the United States? You should come to our home in Paris, Roger suggested. We have a family archive there.

It took me a few more yearslife happens; I wasnt in a hurrybut eventually I made it to the Malina house. Roger opened the gate and welcomed me through the courtyard into the home where he grew up. Tucked away off a quiet back street in Boulogne-Billancourt, the house exudes a kind of homely modernism: simple concrete lines, a quirky spiral staircase, high ceilings and low furniture. In the study was a panorama of books, photographs and paintings, preserved in a state of lifelike disorder.

In the adjacent office I scanned the shelves. Each was laden with box files of letters, drawings, photos, sketches, more letters, magazines, exhibition catalogues, receipts, so many letters. There were documents of every conceivable kindmany of them intimate rather than institutional. Love letters. Letters to his mother. There were more formal papers too: a thick correspondence with lawyers, an archive box on which was written Box V: Witchhunt file. Franks life felt so close at hand, it was as if he had just stepped out to the patisserie. On his bedside table I spotted his wristwatch, a tiny calendar clipped to the strap: November 1981.

I had only been in Paris for a few hours when I realised that what had been an idle curiosity on Cleatrabhal, then an academic interest in Londons National Archives, was now something urgent and personal. Here was an extraordinary life. I didnt know the full story then, not even half of it, but I felt certain that there was a story.

With Rogers permission, I photographed everything I could find, page by page, and read the material back in Scotland. I filled notebooks with details of Malinas friends and colleagues. I pieced together his relationships from the letters, working out who he trusted and who he didnt. I started to find gaps: letters missing; things that didnt add up. I found Frank Malinas FBI file and blinked at some of the allegations it contained. I submitted my own Freedom of Information requests to declassify the FBI files on Malinas friends. There were thousands of pages to examine in this house, but it was only a starting point; the search took me spiralling outwards, into other circuits of association.

The momentum I built up in Franks archive was dragged by the search for FBI files. First you have to prove that the subject is dead and provide enough information (social security number, dates of birth, death, marriage) to identify the relevant files. If any are found you then join the declassification queue; that can take five years. Released files have many of the names redactedblacked outso that although you have some idea of what has happened, its difficult to know