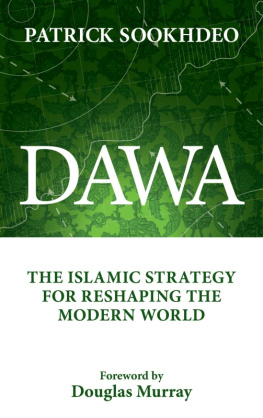

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

C. CHRISTINE FAIR

In Their Own Words

Understanding Lashkar-e-Tayyaba

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

C. Christine Fair, 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: C. Christine Fair.

Title: In Their Own Words: Understanding Lashkar-e-Tayyaba.

ISBN 9780190062040 (epub)

CONTENTS

Dedicated to the victims of terrorism and their families everywhere. May they find peace and justice.

This project is the culmination of research I unwittingly began in Lahore in 1995 when I was a doctoral student studying Urdu as well as Punjabi through the renowned BULPIP (Berkeley Urdu Language Program in Pakistan, currently known as the Berkeley-AIPS Urdu Language Program in Pakistan). As a student of South Asian Languages and Civilizations, I frequented Anarkali Bazaar in Lahore, where I first encountered booksellers purveying the propaganda of Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (LeT), which now operates mostly under the name of Jamaat ud Dawah (JuD). I began collecting their materials that year and continued to do so during subsequent visits over the next couple of decades, until I was ultimately deemed persona non-grata by the countrys intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI).

Due to the ISIs assessment that I am a nasty woman, I have been unable to return to Pakistan since August 2013, but astonishingly, I was able to continue gathering materials for this effort through inter-library loan. Since 1962, American libraries have procured books from South Asia through the so-called PL-480 program, named after the eponymous public law which allowed the US Library of Congress to use rupees from Indian purchases of American agricultural products to buy Indian books. In 1965, a field office was opened in Karachi to oversee the acquisition of Pakistani publications. While the PL-480 program was long since discontinued, The Library of Congress continues to use the same institutional infrastructure to purchase these publications under the guise of a new program called the South Asia Cooperative Acquisitions Project.

I am deeply indebted to the Library of Congress and the other libraries across the United States which purchased these publications through this program and made them available to scholars through their institutions interlibrary loan programs. I am particularly beholden to Georgetown Universitys Lauinger Library, which never failed to produce a book I requested. The University of Chicago and the Library of Congress were the primary sources of these books and I am grateful that they continue to obtain and lend terrorist publications. As one US government official wryly noted when I explained my new sources of materials, there is no better way to keep terrorist literature out of the hands of would-be terrorists than putting it in a library.

I am also extremely indebted to Georgetown University, which has supported my work unstintingly since I joined the Security Studies Program in the fall of 2009. The University and the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University subsidized the writing of this book through a year-long leave through sabbatical and a senior research leave. Moreover, the School of Foreign Service provided invaluable financial support that enabled me to collaborate with Safina Ustaad, who did most of the translations used in this volume. (Ustaad and I are publishing a subsequent volume that contains these translations via Oxford University Press, entitled A Call to War: The Literature of Lashkar-e-Tayyaba.) The School of Foreign Service also subsidized a related and ongoing project in which I am studying the battle-field motivations of Lashkar-e-Tayyaba fighters. Through that funding, Ali Hamza translated a 10 per cent random sample of the over 900 fighter biographies I collected, the analyses of which I present in this book. I am also grateful to the Security Studies Program, my home program within the School of Foreign Service, for generously subsidizing other aspects of this project, such as my work with Abbas Haider and other ongoing collaborations with Ali Hamza. Both Haider and Hamza translated some materials (under my guidance and quality assurance) which I have analyzed herein. Ali Hamza has been a superb colleague and collaborator over numerous years on several quantitative and qualitative projects alike. I am extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity to work with such a gracious and talented colleague.

I also benefited tremendously from fellowships with the Institute for Defense Studies and Analysis (IDSA) in New Delhi, which hosted me as a senior fellow in the summer of 2016, the Gateway House in Mumbai during the summer of 2015, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) in Washington DC, which hosted me as a fellow in the summer of 2017. I remain obliged to Jayant Prasad, Rumel Dahiya, and Ashok Behuria at IDSA, and Sally Blair at the NED. Don Rassler and the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) at West Point also provided important resources for the quantitative aspects of this project while I was a fellow at the CTC. It was a privilege to work with Don and the other members of that team including Anirban Ghosh, Nadia Shoeb, and Arif Jamal to whom I am deeply beholden. I would also like to express my gratitude to Oxford University Press which graciously allowed me to compress, update and draw upon significant portions of Fighting to the End: The Pakistani Armys Way of War (2014) as well as Taylor and Francis which granted me permission to draw heavily from a 2014 article in the The Journal of Strategic Studies (Insights from a Database of Lashkar-e-Taiba and Hizb-ul-Mujahideen Militants, Journal of Strategic Studies, 37, 2 (2014), pp. 259290.)

As this volume is the culmination of years of research and consultation, it would be remiss were I not to mention the superb community of scholars with whom I have discussed this project and data. Those who have been generous with their time and insights include: Daniel Byman, Bruce Hoffman, Jacob Shapiro, Praveen Swami, Ashley Tellis, Arif Jamal, Maryum Alam, the late Mariam Abou Zahab, Jaideep and his colleagues, and numerous others who met with me over the years in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh. Seth Oldmixon deserves a special mention. Oldmixon is one of the most under-valued assets in the community of South Asia analysts. He has a hawks eye for details as he has scoured social media feeds and publications of militant organizations, reads the South Asian press more diligently than most intelligence analysts I know and has an extraordinary ability to recall events, identify persons and their associations.