ALSO BY PAMELA CONSTABLE

Fragments of Grace:

My Search for Meaning in the Strife of South Asia

A Nation of Enemies: Chile Under Pinochet

(with Arturo Valenzuela)

Copyright 2011 by Pamela Constable

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of

The Random House Publishing Group, a division of

Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Constable, Pamela.

Playing with fire / Pamela Constable.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60345-0

1. PakistanPolitics and government1988 2. Pakistan

Social conditions21st century. 3. Islam and politicsPakistan.

4. Islam and statePakistan. 5. Islamic fundamentalismPakistan.

6. DemocracyPakistan. 7. Constable, PamelaTravelPakistan.

I. Title.

DS389.C65 2011

954.91053dc22

2011012621

www.atrandom.com

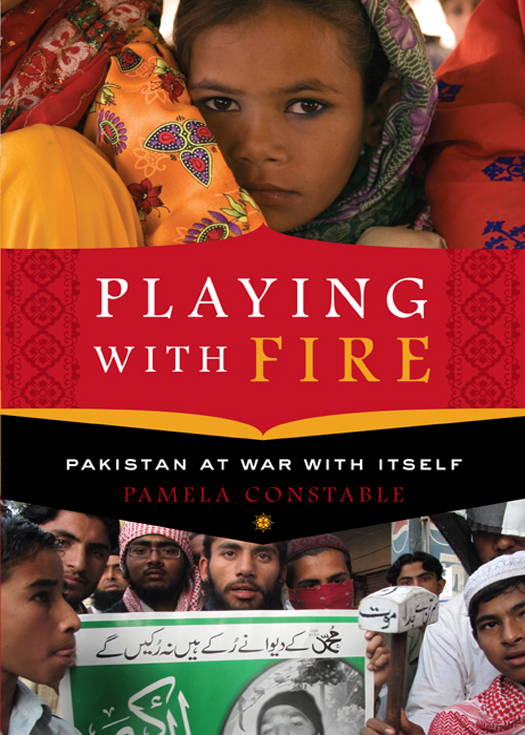

Jacket design: Kimberly Glyder

Front-jacket photographs: Annie Griffiths Belt/Corbis (top), courtesy of the author (bottom)

Spine photograph: courtesy of the author

Back-jacket photographs: Lichtmeister/Shutterstock (top), Asianet-Pakistan/Shutterstock (bottom)

v3.1

Gods purpose for man is to acquire a seeing eye and an understanding heart.

J ALAL AL -D IN R UMI, A.D . 12071273

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

The Flood

CHAPTER 2

Sahibs

CHAPTER 3

Honor

CHAPTER 4

Hate

CHAPTER 5

Khaki

CHAPTER 6

Talibanization

CHAPTER 7

The Siege

CHAPTER 8

The Girl from Swat

CHAPTER 9

Justice

CHAPTER 10

Drones

CHAPTER 11

The Murder of Democracy

introduction

PAKISTAN IS A VAST and diverse society of some 175 million people who inhabit scattered pockets of clan and class, religion and ethnicity, poverty and power. It has a thousand separate worlds that may coexist at close quarters but never intersect.

It is a tribal chief sleeping with an arsenal under his bed; a fashion model strutting across a stage; a beggar gulping soup in a Sufi shrine; a fiery cleric exhorting acolytes to martyr themselves for Islam; a tiny girl making bricks all day in the sun; a society bride in glittering crimson; a colonel watching his son receive a medal for bravery; a family of flood victims waiting in an empty tent.

Pakistan is a country of existential as well as cultural contradictions, some of which have not been resolved since it was founded six decades ago. It is a constitutional democracy in which many people feel they have no access to political power or justice. It is an Islamic republic in which many Muslims feel passionate about their faith but are confused and conflicted over what role Islam should play in their society.

It is a proud nuclear power that yearns for global respectability but mistrusts its neighbors and resents its allies. It is a teeming hive of activity in which many people feel too trapped to move. It is a national security state under siege from terrorists that selectively coddles violent extremist groups.

This book is an attempt to explain to Western readers what Pakistani society is like today: what matters to Pakistanis, how they live and work, what frustrations and hopes they harbor, whom they fear and admire, and what forces shape their lives and opinions.

It is not an investigative work aimed at ferreting out the secrets of powerful institutions or radical movements. It does not try to keep up with every incremental news development or to predict what lies ahead for the war on terror and the ambivalent relationship between Pakistan and the United States.

Rather, it is an attempt to create a backdrop for a dangerous and fluid moment in the history of a troubled but important country, and to explain what is enduring and changing in its life as a nation. It is an attempt to explain such puzzles as why Pakistanis have a love-hate relationship with the West, why the coup-prone army remains the nations most respected institution, and why the feudal mind-set still dominates politics. It explores why a country with such enormous economic potential has failed to educate and employ a majority of its people, and why a nation founded with such high hopes as a modern Muslim democracy has struggled so painfully to live up to them.

In all of these issues lurks the same, central question: why is Pakistan, with its huge military establishment, democratic form of government, and tradition of moderate Muslim culture, failing to curb both the growing violent threat and the popular appeal of radical Islam?

OVER THE PAST DECADE , I have traveled widely in Pakistan and explored many of its worlds, from Sufi shrines to Deobandi seminaries, from fashion shows to flooded villages, from brick quarries to bombed bazaars.

The most important thing I have learned is that many Pakistanis feel they have no power. They see the trappings of representative democracy around them but little tangible evidence of it working in their lives. They feel dependent on, and often at the mercy of, forces more powerful than they: landlords, police, tribal jergas, intelligence services, politicized courts, corrupt bureaucrats, and legislators tied to local power elites. People do not trust the system, so they feel they need a patron to get around it. This in turn makes everyone complicit in corruption, especially its victims.

The feeling of powerlessness and injustice, which people expressed everywhere I went in Pakistan, is perhaps the most significant factor in explaining the appeal of the Taliban and other religious extremists. They appear to offer justice in a society where that is hard to come by, even if people may not understand what the extremists brand of justice would look like. They also offer an opportunity for those who feel excluded, especially the young and poor, to join a movement that has elements of a moral crusade or revolution, even if it seems like thuggery from the outside.

The second important thing I learned is that in Pakistan, truth is an elusive and malleable commodity. In Afghanistan, another country where I have spent a lot of time, things are often spelled out in black and white: fight or die, eat or starve, guest or enemy. Afghans survive by making hard choices, but they make them with defiant pride. In Pakistan many things are gray and murky, and people survive by playing the angles, ducking their heads, and reinventing themselves. Truth is elastic, fleeting, and subject to endless political manipulation.

Major assassinations are rarely solved, and there is often a feeling that it is convenient for them not to be solved. Court cases are chaotic affairs with myriad versions of events, suspects pressured to confess or recant, and innocent people charged or released through bribes. Political promises are easily made and rarely kept. People are considered foolish if they pay taxes, creating a permanent culture of tax evasion. The current president has been accused and jailed in numerous corruption cases but never convicted, and the truth will probably never be known.

In foreign affairs, central aspects of Pakistans behavior toward other nations are either covert, duplicitous, or routinely denied, such as the longtime official fiction that Pakistan extended only moral and political support to the insurgency in Kashmir, or the recent official fiction that Pakistan has not maintained links to selected Islamic militant groups as a source of potential pressure on India and strategic depth in Afghanistan. After the terrorist siege in Mumbai in 2008, Islamabad denied for weeks that the surviving commando belonged to a Pakistani militant group that had been officially banned but secretly supported by the state for years.