Contents

Guide

For Alice, Felix and Jacob

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St Georges Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Christopher Hale, 2019

The right of Christopher Hale to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9289 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Over the years I learned which hooks to use to catch which fish.

Hungary really offered the Jews to us like sour beer, and Hungary was the only country where we could not work fast enough.

If we had killed 10.3 million Jews, then I would have been satisfied and would say, good, we annihilated an enemy. I wasnt only issued orders, in this case Id have been a moron, but I rather anticipated, I was an idealist.

Adolf Eichmann, Sassen interviews, 1957

Kasztner: Ive wondered many times whether, instead of the negotiations, it wouldnt have been better to call on the Zionist youth and rally the people to active resistance to entering the brickyards and the wagons.

SS officer Kurt Becher: You wouldnt have achieved anything this way.

Kasztner: Maybe, but at least we would have kept our honour. Our people went into the wagons like cattle because we trusted in the success of the negotiations and failed to tell them the terrible fate awaiting them.

KasztnerBecher minutes, 15 July 1944

CONTENTS

A NOTE ON THE AUSCHWITZ CONCENTRATION CAMP

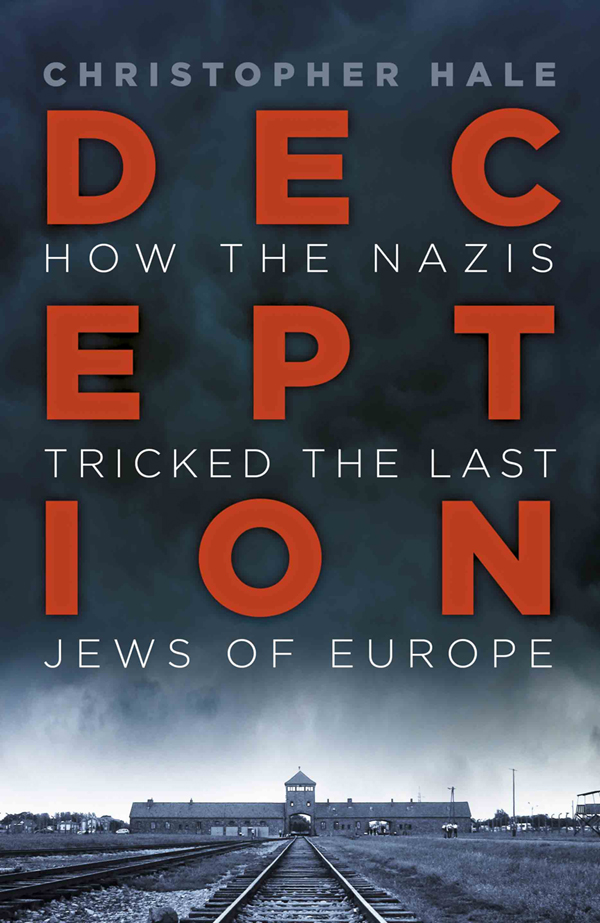

Auschwitz is today the most notorious site in the memorial topography of the German genocide. The Second World War is now viewed through the lens of the Holocaust and the memorialisation of this genocide is seen through the lens of Auschwitz. Historians now recognise that the murderous German onslaught on European Jewry was not initiated inside the KL (concentration camp) system. A huge proportion of the more than 5.5 million Jews murdered under the Nazi regime were killed in ditches, forests, fields and burial pits across Eastern Europe and only later in the specialised death camps such as Treblinka, Sobibr, Chemno and Beec. In the aftermath of the Wannsee Conference convened in February 1942, Himmler issued an order: Jews into the KL. From mid 1942 until the end of the war, the majority of Jews were deported to specialised camps to be worked to death if they were deemed fit, or murdered. A second important point is that Auschwitz (the German word for the Polish town of Owicim) was an archipelago of camps that had many different functions in the KL system administered by the SS. The SS managers ordered the construction of facilities to carry out mass killings at Auschwitz II, which was originally built in 1941 on the cleared site of a village called Birkenau (Bezinka).

Birkenau was not built to exterminate Jews but to incarcerate Soviet prisoners of war; however, in March 1942 the SS began to deport European Jews there and constructed gas chambers and crematoria to incinerate corpses. Inside the Auschwitz camp archipelago, Birkenau was transformed as a specialised extermination facility and entered its most lethal phase in the spring and summer of 1944. Between 1940 and 1945, approximately 1.3 million people were transported to the Auschwitz complex: 1.1 million perished. Nine-tenths of those killed ended up there because of their Jewish origin, and every third victim was a Hungarian citizen. The largest group of victims were Hungarian citizens. I have used Auschwitz to refer to Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

PRELUDE: CAIRO, JUNE 1944

On 14 June 1944, in the early hours of the morning, the twice-weekly train from Haifa in the British-mandated territory of Palestine pulled into the main station at Bab el Hadid, the Iron Gate, in Cairo. As the big, sand-dusted locomotive exhaled a gasping wheeze of steam, a British military police officer emerged from the carriage behind the engine. He was quickly followed by a stocky, middle-aged man who sweated profusely in a crumpled brown suit that had seen better days. He was a Hungarian Jew called Joel Brand and he was to all intents and purposes a prisoner of the British. For a few moments, Brand hesitated, blinking in the harsh light that pierced the station roof and blinded by a torrent of perspiration, before he descended unsteadily to the platform.

Brands journey to Cairo had begun six weeks earlier and more than 3,000 miles away in Budapest, and he had already endured many tribulations. Months earlier in March, Adolf Hitler had ordered German troops to occupy Hungary. His loyal henchman, Heinrich Himmler, the Chief of the SS, had despatched a Special Commando led by SS Colonel Adolf Eichmann to liquidate the last intact Jewish community in Europe numbering some 800,000 souls. Brand had taken to referring to himself as the emissary of the doomed and many who encountered him feared for his state of mind. His fragility is not difficult to understand for he had an astonishing tale to tell. He had been entrusted, he claimed, with a mission to barter the lives of a million Hungarian Jews for 10,000 military trucks. This perplexing yet tantalising ransom offer had been put to Brand by Eichmann with the approval, Brand alleged, of Himmler himself.

What would soon become infamous as the Blood for Trucks offer was already being dissected, pondered, disputed and quarrelled about in the corridors of power in Washington, London and Moscow. It would seem that the unprecedented offer to ransom lives was a tiresome inconvenience for the Allied warlords. At every waking moment in his long journey, the weight of these million lives, among them his wife and sons, weighed heavily on Joel Brands soul. They haunted his nightmares. That day in Cairo, he was not aware that Eichmann and his Hungarian collaborators were herding tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews into cattle cars every day and despatching them to the Auschwitz camp in occupied Poland. There, in the words of Paul Celan, the sky became their grave.

In Egypt, the summer heat was brutal even at this early hour. The British police officer firmly placed a hand on his prisoners shoulder and guided him towards the swarming and cacophonous station entrance, lit by low beams of sunlight cutting through swirling clouds of dust stirred up by the great army of hawkers lured to the great station. A British army staff car stood parked, its engine muttering fitfully, in front of the main entrance. The policeman, who had accompanied Brand from Haifa, opened the back door with a tight smile. The elderly Egyptian driver waited impassively, then without so much as a glance behind, steered the car into the churning flow of heavily laden donkeys, camels, carts, trams and motor vehicles that eddied perpetually around the Iron Gate.