Table of Contents

ALSO BY RONALD FLORENCE

NONFICTION

Lawrence and Aaronsohn

Blood Libel

The Perfect Machine

The Optimum Sailboat

Marxs Daughters

Fritz

FICTION

The Last Season

The Gypsy Man

Zeppelin

Ronald Florence

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2010 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Ronald Florence, 2010

All rights reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICAION DATA

Florence, Ronald.

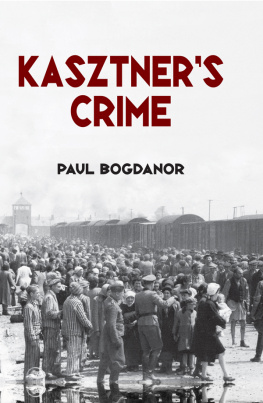

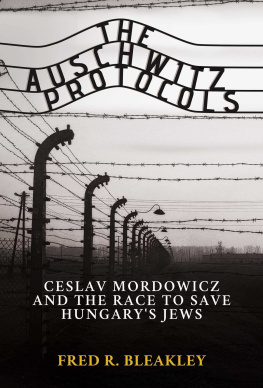

Emissary of the doomed : bargaining for lives in the Holocaust / Ronald Florence.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN : 978-1-101-18984-9

1. JewsPersecutionsHungary. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)Hungary. 3. World War, 1939-1945JewsRescueHungary. 4. Brand, Joel, 1906-1964. 5. HungaryEthnic relations. I. Title.

DS135.H9F66 2010

940.53183509439dc22 2009035922

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

To the memory of the hundreds of thousands

who might have been saved

What a misery to be a minority: Hungarian & Jew.

Arthur Koestler

Whoever has caused a single soul to perish from mankind Scripture imputes it to him as though he had caused a whole world to perish. And whoever saves alive a single soul from mankind Scripture imputes it to him as though he had saved alive a whole world.

Mishna Sanhedrin 4:5

Budapest, April 1944

At that time we knew nothing of Auschwitz.

Philip von Freudiger

God has sent me ahead of you to ensure your survival on earth, and to save your lives in an extraordinary deliverance.

Genesis 45:7

On the morning of April 25, 1944, his thirty-eighth birthday, Joel Brand waited outside the Caf Opera, across from the Budapest opera house on Andrssy Avenue. Normally, the early hour wouldnt have bothered him: the view of the grand Renaissance-style opera house through the leafy trees was restful, the caf usually had a lively crowd, and it was never too early to find good conversation. But that morning Joel Brand was nervous and uneasy.

By 1944, caf life in most of central Europe had been reduced to ersatz coffee and cautious whispers. Wall posters listed verboten activities punishable by death. It was forbidden to walk on the streets between nine at night and five in the morning; forbidden to keep firearms; forbidden to aid, abet, or shelter escaped prisoners, enemy soldiers, or citizens of countries considered enemies of Germany; forbidden to listen to foreign radio broadcasts; forbidden to refuse German currency; forbidden to be in possession of newspapers other than Nazi-approved official rags. In Prague, Vienna, Bratislava, or Krakow, the cafs were quiet: years of German occupation had made fear too palpable for talk. But Budapest was different. In Budapest, the cafs were still lively. Musicians played, including an occasional fiddler or guitarist who knew something other than the traditional gypsy tunes. You could order Colombian coffee, sweet Tokay wine, fruit brandies, even real pastry if you knew where to look. Women came to the cafs, servant girls in embroidered blouses and full skirts, stylish women in Paris fashions, and the beckoning women who worked the cafs and nightclubs in the evenings. Country gentry showed up in tall boots with pheasant feathers in their hats. And there was conversationbusiness deals, furtive romances, and the relentless cynicism and wit of the wags.

In April 1944, only a month after German troops occupied Hungary, the Jews of Budapest found themselves living under unwelcome new restrictions, but they had not been confined to ghettos. They could still spend time with friends, meet for prayers, attend makeshift concerts, carry on love affairs, try to pursue their professions and businessesand they were welcome in at least some of the cafs. Joel Brand was at home in that demimonde, a devotee of the pastry and brandy, the women, the card games, and especially the conversations. Officially, he was in the knitwear business with his wife Hansi, an attractive woman, dark, voluptuous, long-legged, and buxom. Hansi managed their workshop on Rozsa Street, not far from Andrssy Avenue and the Opera, where ten or twelve weavers picked up leather, patterns, and yarn and brought back stylish leather and knit gloves and fancy stockings. While Hansi ran the workshop, Joel was supposed to sell the gloves and stockings. He was gregarious, effective at selling, and adept at ferreting out black market goods that werent readily available in the shops, like silk stockings, filtered cigarettes, French fragrances, and fine cake flour. But he wasnt happy as a salesman. He preferred meeting women, drinking, playing cards, and caf talk. On a good night at poker he could win what he earned in a week of selling gloves. And he had discovered a pursuit even more exciting than poker.

Working with other Zionists in a secret organization called Vaada, the Hungarian rescue and aid committee,

Brand and his colleagues in Vaada could only rescue a few individuals at a time, but in late 1943, Oskar Schindler, a factory owner in Silesia, had come to Budapest and dined at the fancy Gellrt Hotel, on the Buda bank of the Danube, with Joel Brand and Dr. Schmidt. Brand found Schindler fascinating. Schindler had owned a series of profitable businesses, and from the stories he and others told, he was adept at dealing with the Nazi authorities. By getting his businesses declared essential to the German war effort he succeeded in manipulating his way through the Nazi bureaucracies so he could employ and harbor Jewish workers even while the Jewish populations of the area were being systematically ghettoized and deported. Schindler was aware that Jews from Poland and Slovakia were being smuggled to safety in Hungary. He had contacts with Vaada and had carried funds to Europe from Istanbul for the Jewish Agency. He also knew how to cultivate the German agents and quickly picked up Dr. Schmidts habit of referring to Jews as children.