GREAT STATE

ALSO BY TIMOTHY BROOK

Sacred Mandates (with M. van Walt and M. Boltjes)

Mr Seldens Map of China

The Troubled Empire

Vermeers Hat

Collaboration

The Confusions of Pleasure

Quelling the People

GREAT STATE

CHINA AND THE WORLD

TIMOTHY BROOK

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

29 Cloth Fair

London

EC1A 7NN

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Timothy Brook, 2019

Cover design: Sinem Erkas

Cover images: Getty

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781781258286

eISBN 9781782833475

To Fay Sims:

To misquote a poem Anne Bradstreet wrote for her husband a year or two before the fall of the Ming, when China was still exotic,

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever wife were loved by man, then thee;

I prize thy love more than whole mines of gold,

Or all the riches that the East doth hold.

There exists a paramount boundary within Heaven and Earth: Chinese on this side, foreigners on the other. The only way to set the world in order is to respect this boundary.

Qiu Jun (142195), quoted in

There are principles common to both East and West.

Xu Guangqi (15621633), quoted in

List of Maps

. Azimuthal equidistant projection of the globe from China.

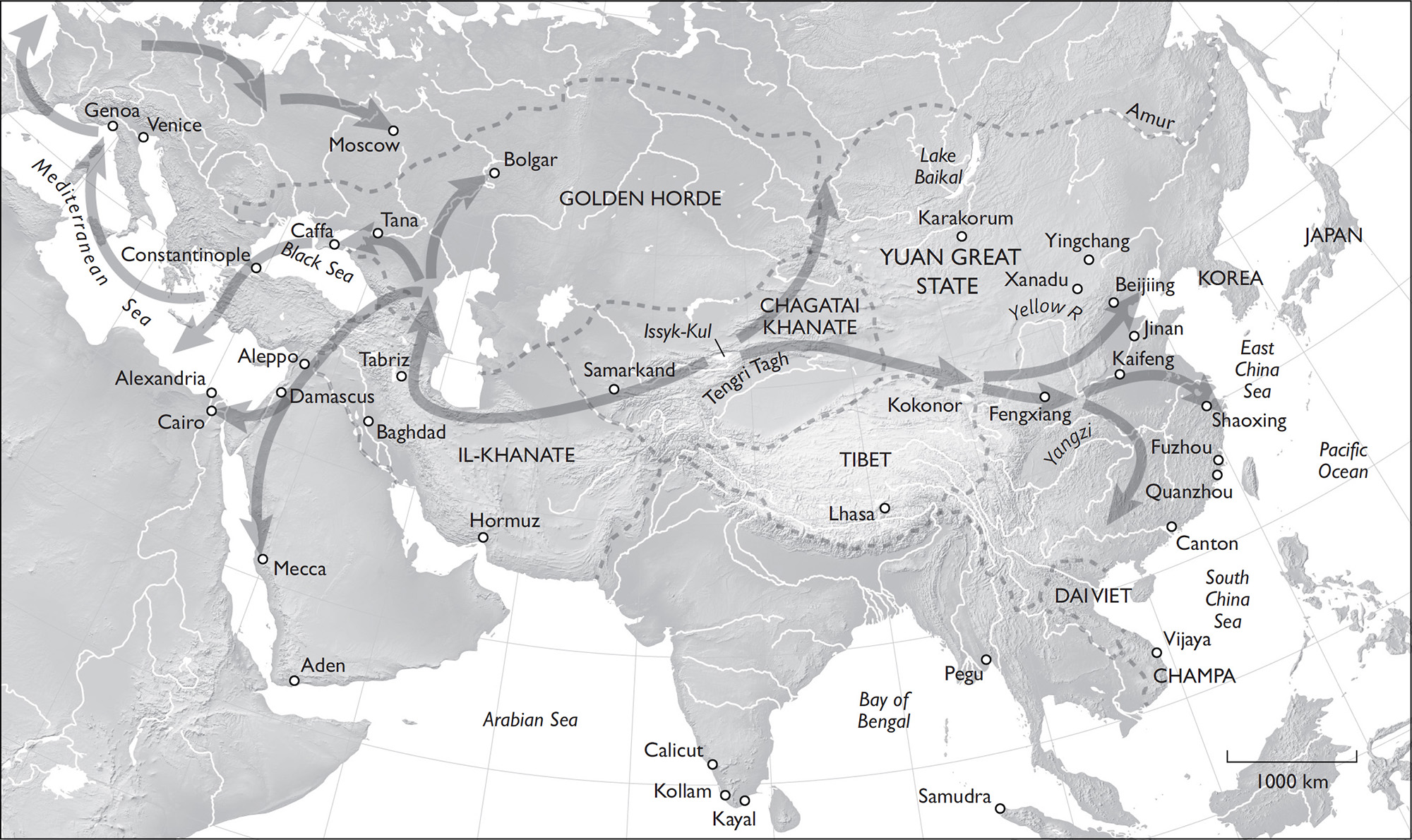

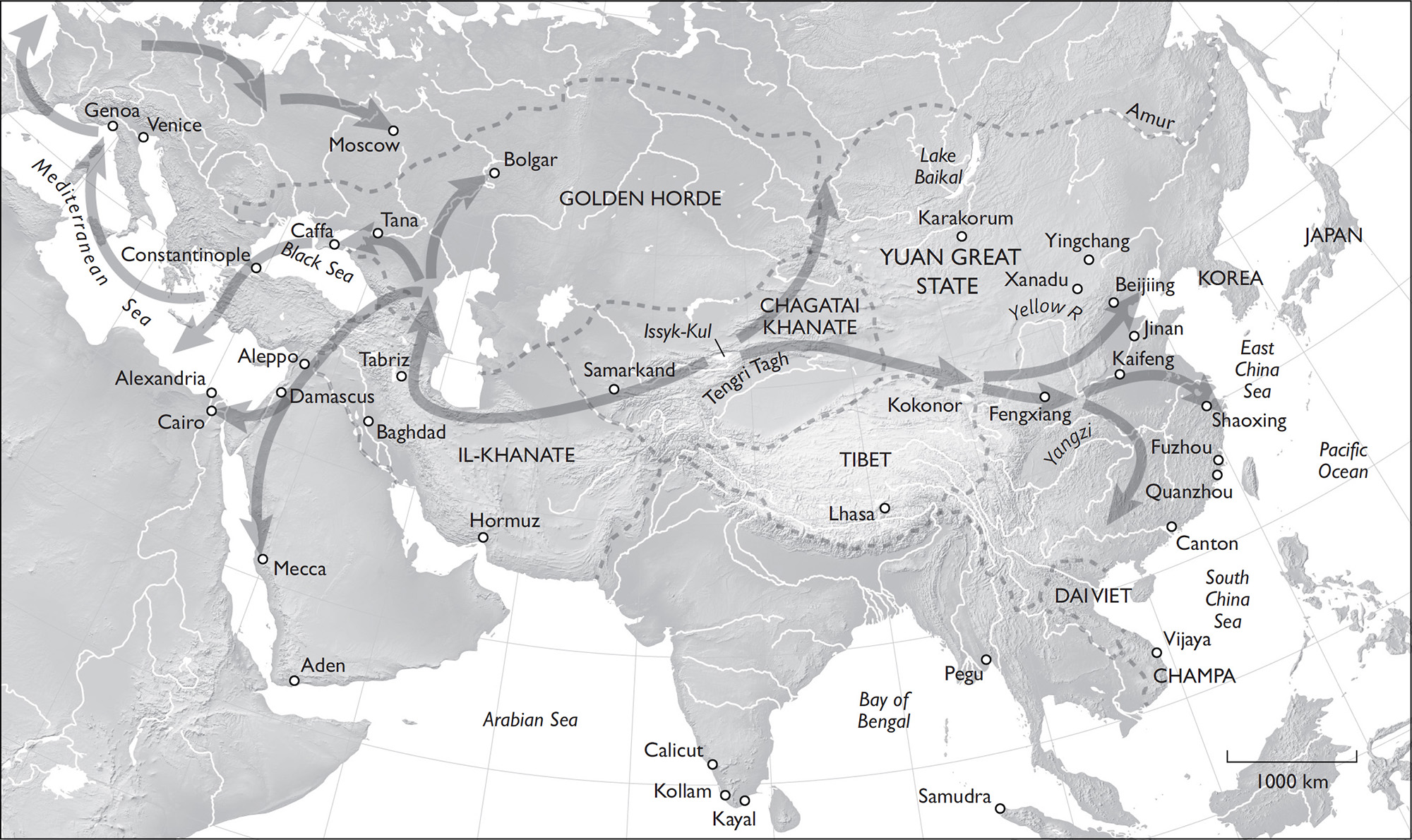

. The movement of the Black Death across Eurasia between the 1330s and the 1360s.

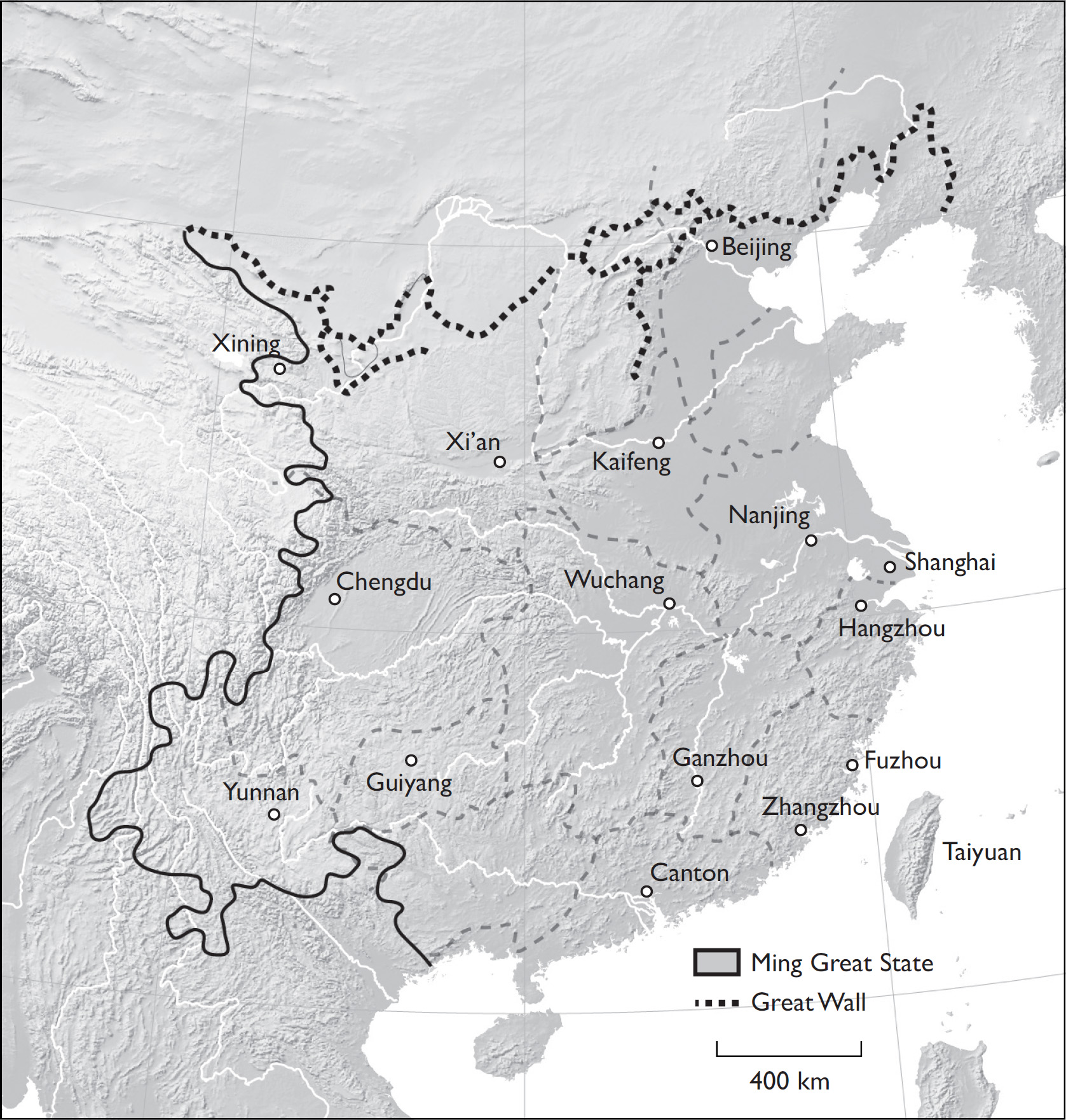

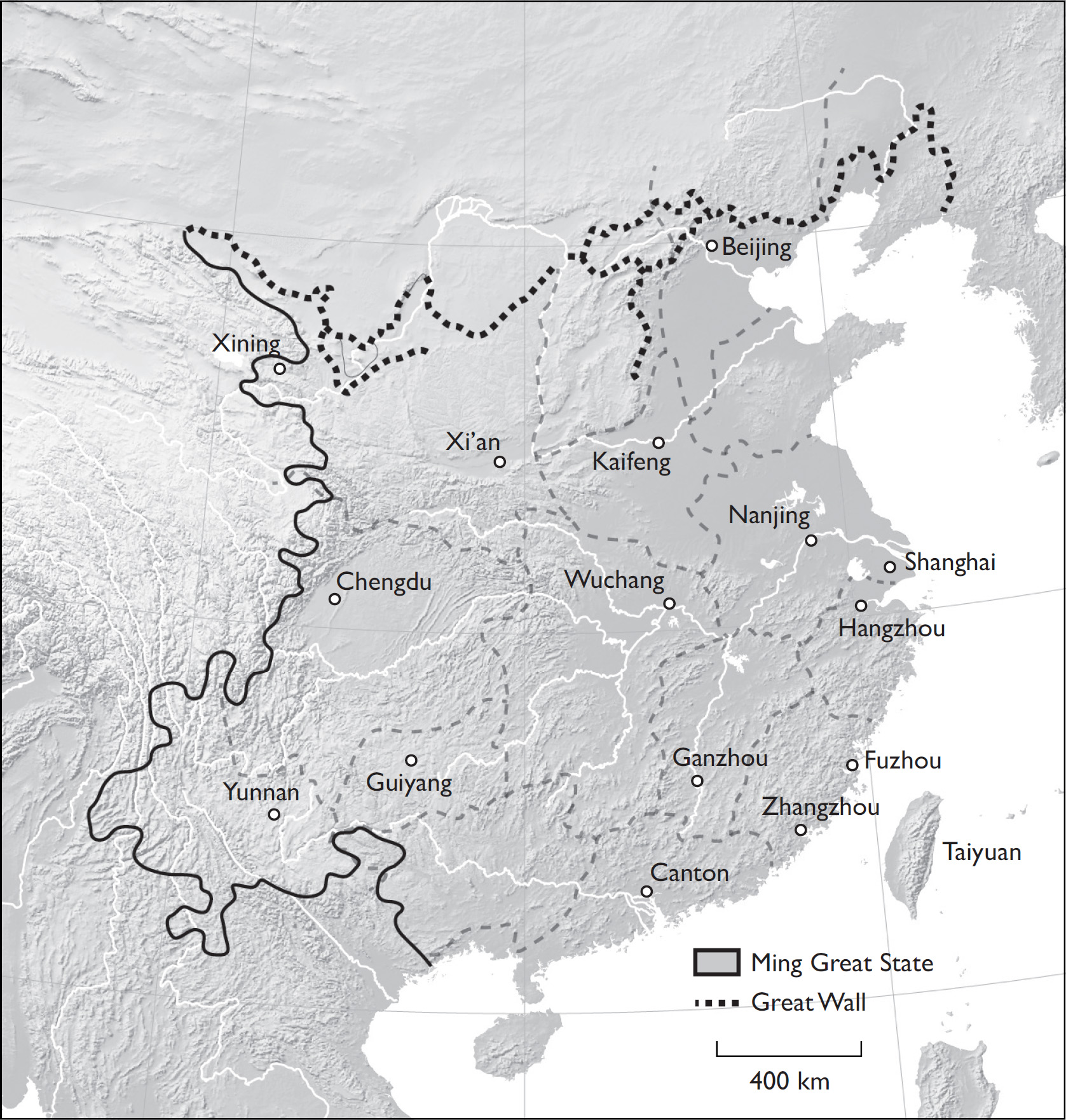

. China under the Ming Great State.

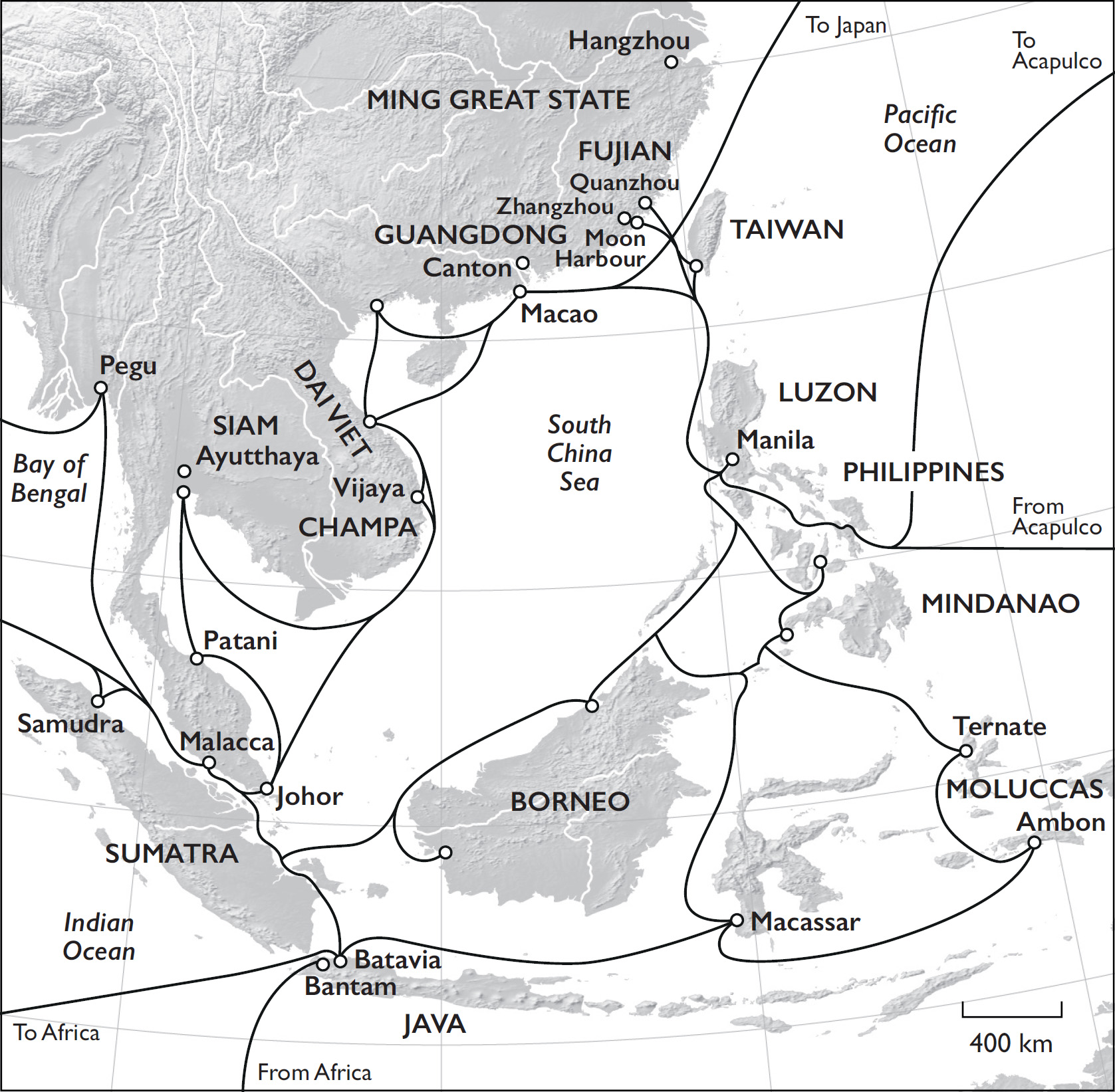

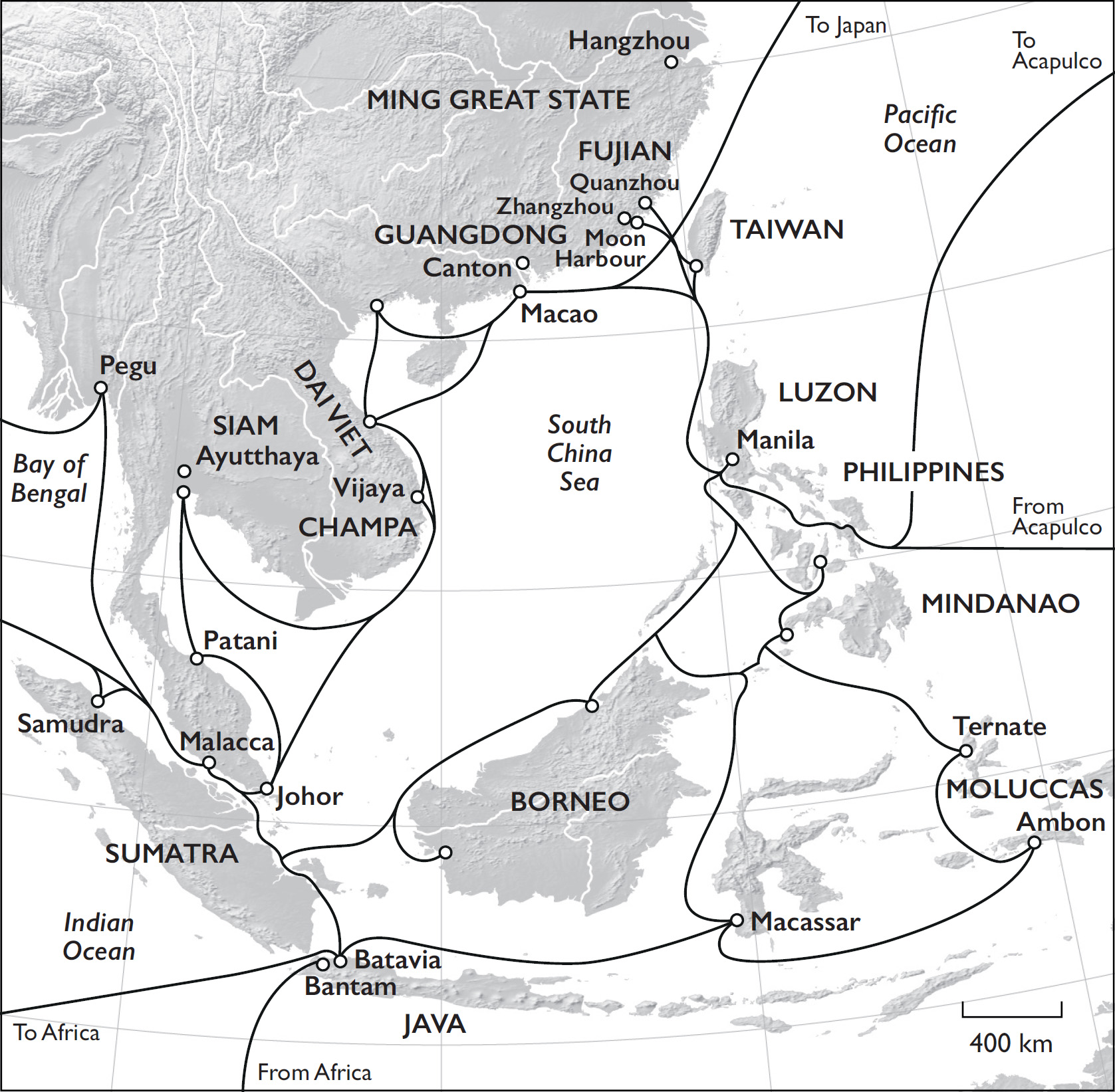

. Maritime connections around the South China Sea, c. 1604.

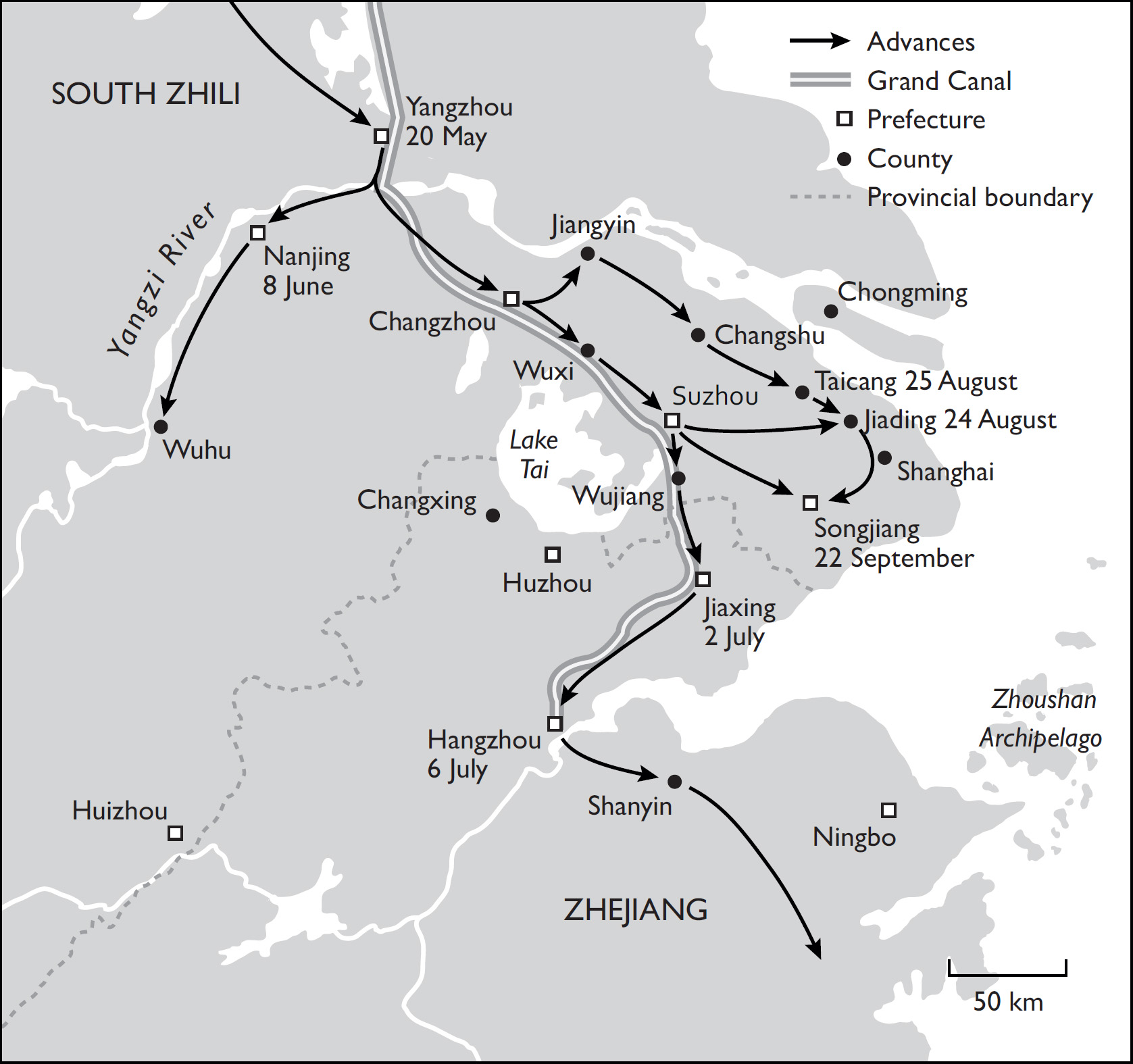

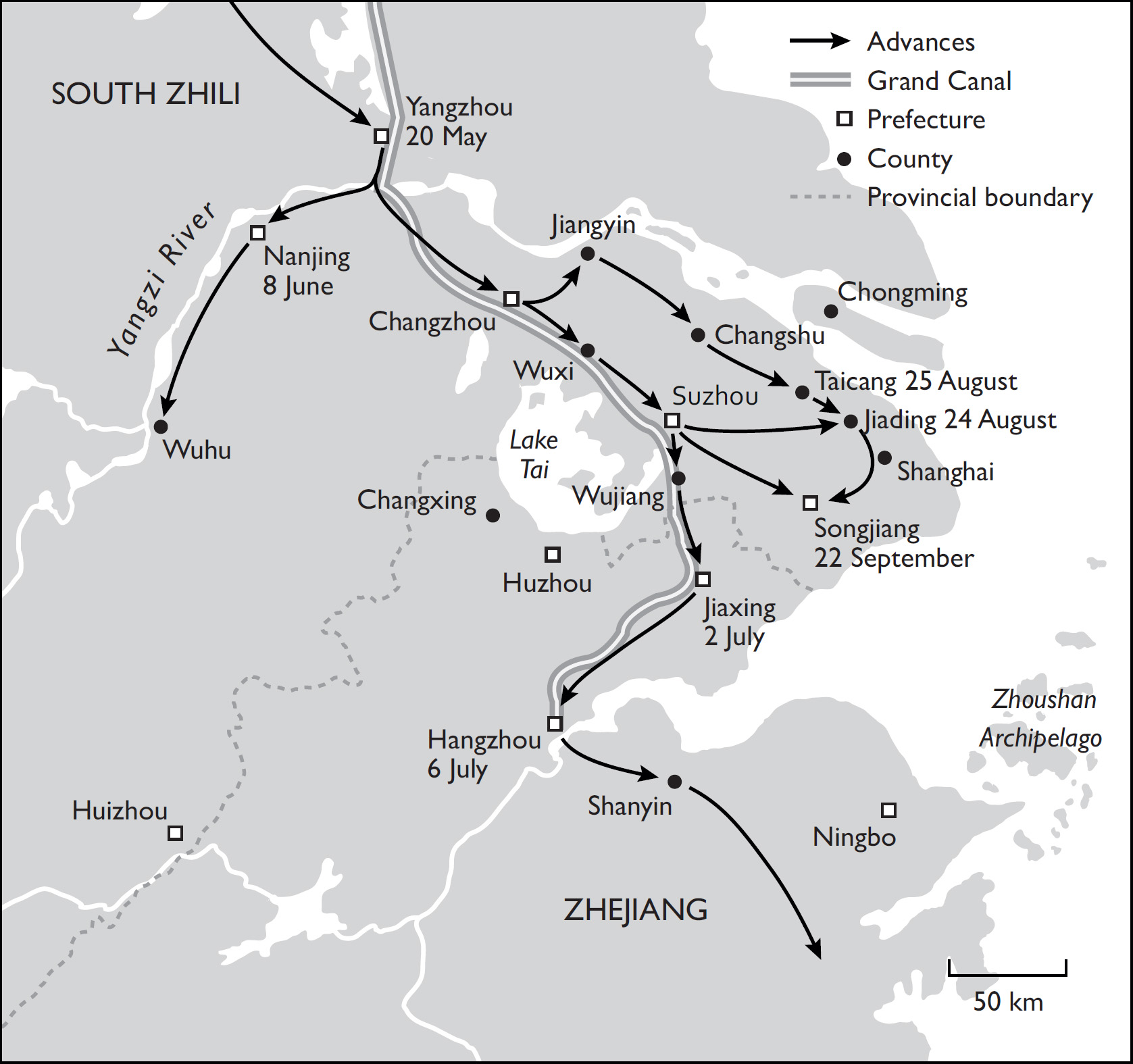

. Manchu conquest of the Yangzi Delta, May-September 1645.

. The territorial extent of Japans wartime occupation of China, c. 1940.

The maps were drawn by Eric Leinberger.

1. Azimuthal equidistant projection of the globe from China.

2. The movement of the Black Death across Eurasia between the 1330s and the 1360s.

3. China under the Ming Great State.

4. Maritime connections around the South China Sea, c. 1604.

5. Manchu conquest of the Yangzi Delta, May-September 1645.

6. The territorial extent of Japans wartime occupation of China, c. 1940.

List of Illustrations

Ji Mingtai, Jiuzhou fenye yutu gujin shiji renwu [Terrestrial map of astral correspondences of the nine provinces, with events and personages ancient and modern] (1643); University of British Columbia Library, Vancouver.

Liu Guandao, Khubilai Khan Hunting (1280); National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Khubilai hunting with his leopard, from a manuscript of Marco Polo, Livre des merveilles (Book of Marvels), 31v; Bibliothque Nationale de France, RC-B-01969.

Ghazan and Kkein, from Rashd al-Dn, Jami al-Tawarikh [Compendium of chronicles], Edinburgh University Library Or. MS 20.

Mongol soldiers using a trebuchet in siege warfare; from Rashd al-Dn, Jami al-Tawarikh [Compendium of chronicles], Edinburgh University Library Or. MS 20

The Galle Stele.

The Cantino Planisphere (1502); Biblioteca Estense, Modena, Italy.

Museum in Nuremberg, is reproduced here from Bridgman Images. The transcription is reproduced from Encyclopedia Larousse illustre (Paris: Larousse, 1898).

Scroll painting of a Korean envoy departing from Nanjing (c.1410s); National Museum of Korea, Seoul.

Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi, from Athanasius Kircher, China illustrata (1667), Burns Library, Boston College.

Baptista van Doetecum, map of Bantam (1596); (public domain).

Suicide of Emperor Chongzhen, from Martino Martini, Regni Sinensis Tartaris tyrannic evastati depopulatique concinna enarratio (Amsterdam: Valckenier, 1661), opposite p. 44; Ghent University Library, BIB HIST.007063.

Portrait of the Seventh Dalai Lama (c. 17501800). Rubin Musem of Art, gift of Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, F1997.30.1 (HAR 380).

Henri-Pierre Danloux and Joseph Grozer, Euhun Sang Lum Akao (London, 1793); Princeton University, East Asian Studies Department, gift of Mr Wallace Irwin Jr, 40.

Instead of Flogging, Morning Leader (6 September 1905).

Torturing a bandit, from an album of punishment scenes by Zhou Peijun (Beijing, early-twentieth century); Turandot (Chinese Torture, Supplices Chinois) website, courtesy of Jrme Bourgon.

Photograph of a young man undergoing torture in the courtyard of a magistrates court after 1900.

Liang Hongzhi leaving his trial, Shanghai, 21 June 1946.

The eastern hemisphere, Haifang tu [map of coastal defence]; Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA.

Change over time: the geographical extent of China in 1600, 1700 and 1800, overlaid on Adrien Brue, Carte gnrale de lempire Chinois et du Japon (Paris: Charles Picquet, 1836); by Noel Macul, courtesy of the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Preface

Not being a writer of big books, I found the proposal of my British publisher Andrew Franklin that I write this book daunting. I prefer small craft to cruise ships. On the other hand, publishers sometimes see what authors cant, so I thank him for launching this project and hope for his sake that the boat floats.

What I have written is not a ponderous tome that slogs through eight centuries of Chinese history dynasty by dynasty or, at least, I hope thats not what is on offer. Rather, I have tried to craft an account for general readers of how China has been in the world since the thirteenth century and what that has meant for the world and for China. I have organised the book not as an elucidation of grand themes but as a series of thirteen moments across seven centuries that reflect significant facets, to me at least, of the historical relationships between China and the world. I want to give readers a chance to see what has happened in particular, concrete situations, before asking you to think about Chinas relationships with the world today.

Two basic ideas drive this book. One is the recognition that China has never not been part of the world, either in the past or in our own day. We have no way to understand China if we separate it from the world. The other is that the fundamental principles guiding the Chinese state today were established not in the late third century BCE, which is where Chinese history usually goes to discover its emergence as a unified state in a long string of dynasties, but in the thirteenth century CE, when China was absorbed into the Mongol world. The Mongol occupation had a profound impact, shifting China from the older dynastic model to a form that, following Mongol usage, I call the Great State. Without this concept we are without a key tool that is needed to understand China from the perspective of history.

Next page