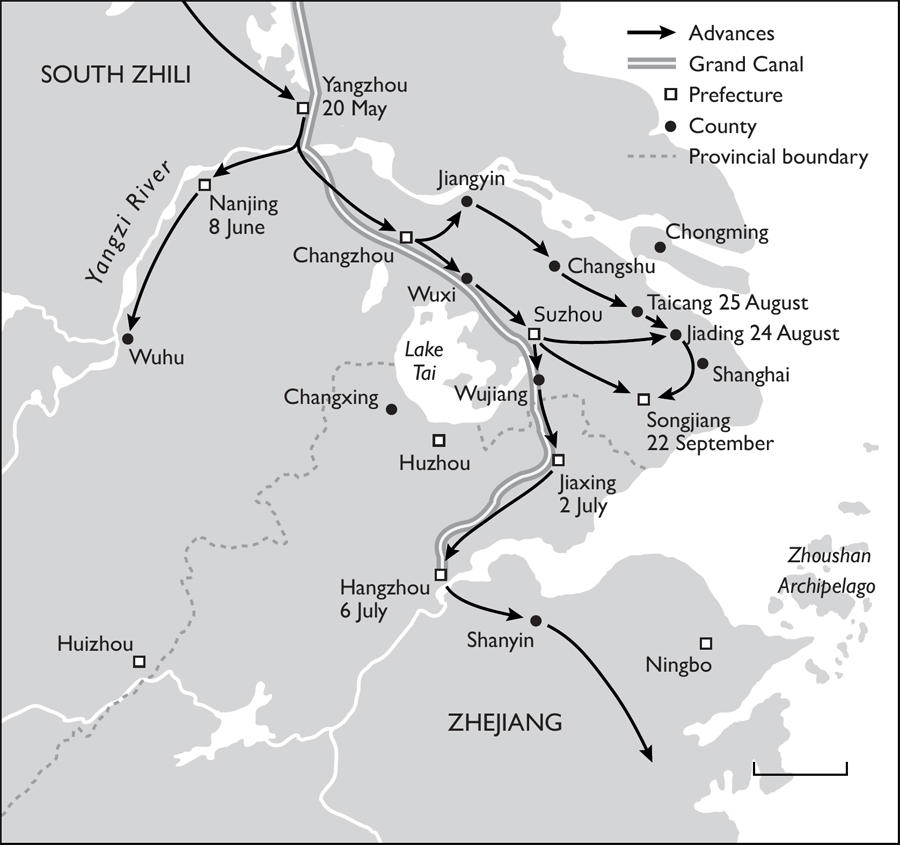

5. Manchu conquest of the Yangzi Delta, May September 1645.

. Ji Mingtai, Jiuzhou fenye yutu gujin shiji renwu [Terrestrial map of astral correspondences of the nine provinces, with events and personages ancient and modern] (1643); University of British Columbia Library, Vancouver.

. Liu Guandao, Khubilai Khan Hunting (1280); National Palace Museum, Taipei.

. Khubilai hunting with his leopard, from a manuscript of Marco Polo, Livre des merveilles (Book of Marvels), 31v; Bibliothque Nationale de France, RC-B-01969.

. Ghazan and Kkein, from Rashd al-Dn, Jami al-Tawarikh [Compendium of chronicles], Topkapi Palace Museum, Reprinted from Pierre Vidal-Naquet, ed., Histoire de lhumanit (Paris: Hachette, 1989).

. Mongol soldiers using a trebuchet in siege warfare; from Rashd al-Dn, Jami al-Tawarikh [Compendium of chronicles], Edinburgh University Library Or. MS 20.

. The Galle Stele.

. The Cantino Planisphere (1502); Biblioteca Estense, Modena, Italy.

. The oceanic side of the globe made for Martin Behaim in 1492, showing Europe and north Africa on the right and Cathay on the left facing each other across the Oceanus Orientalis, the Eastern Ocean. The globe, in the collection of the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg, is reproduced here from Bridgman Images. The transcription is reproduced from Encyclopedia Larousse illustre (Paris: Larousse, 1898).

. Scroll painting of a Korean envoy departing from Nanjing (c. 1410s); National Museum of Korea, Seoul.

. Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi, from Athanasius Kircher, China illustrata (1667), Burns Library, Boston College.

. Baptista van Doetecum, map of Bantam (1596); (public domain).

. Suicide of Emperor Chongzhen, from Martino Martini, Regni Sinensis Tartaris tyrannic evastati depopulatique concinna enarratio (Amsterdam: Valckenier, 1661), opposite p. 44; Ghent University Library, BIB HIST.007063.

. Portrait of the Seventh Dalai Lama (c. 17501800). Rubin Museum of Art, gift of Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, F1997.30.1 (HAR 380).

. Henri-Pierre Danloux and Joseph Grozer, Euhun Sang Lum Akao (London, 1793); Princeton University, East Asian Studies Department, gift of Mr. Wallace Irwin Jr, 40.

. Instead of Flogging, Morning Leader (6 September 1905).

. Torturing a bandit, from an album of punishment scenes by Zhou Peijun (Beijing, early twentieth century); Turandot (Chinese Torture, Supplices Chinois) website, courtesy of Jrme Bourgon.

. Photograph of a young man undergoing torture in the courtyard of a magistrates court after 1900.

. Liang Hongzhi leaving his trial, Shanghai, 21 June 1946.

. The eastern hemisphere, Haifang tu [map of coastal defense]; Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA.

. Change over time: The geographical extent of China in 1600, 1700, and 1800, overlaid on Adrien Brue, Carte gnrale de lempire Chinois et du Japon (Paris: Charles Picquet, 1836); by Noel Macul, courtesy of the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Not being a writer of big books, I found the proposal of my British publisher Andrew Franklin that I write this book daunting. I prefer small craft to cruise ships. On the other hand, publishers sometimes see what authors cant, so I thank him for launching this project and hope for his sake that the boat floats.

What I have written is not a ponderous tome that slogs through eight centuries of Chinese history dynasty by dynastyor, at least, I hope thats not what is on offer. Rather, I have tried to craft an account for general readers of how China has been in the world since the thirteenth century and what that has meant for the world and for China. I have organized the book not as an elucidation of grand themes but as a series of thirteen moments across seven centuries that reflect significant facets, to me at least, of the historical relationships between China and the world. I want to give readers a chance to see what has happened in particular, concrete situations, before asking you to think about Chinas relationships with the world today.

Two basic ideas drive this book. One is the recognition that China has never not been part of the world, either in the past or in our own day. We have no way to understand China if we separate it from the world. The other is that the fundamental principles guiding the Chinese state today were established not in the late third century BCE, which is where Chinese history usually goes to discover its emergence as a unified state in a long string of dynasties, but in the thirteenth century CE, when China was absorbed into the Mongol world. The Mongol occupation had a profound impact, shifting China from the older dynastic model to a form that, following Mongol usage, I call the Great State. Without this concept we are without a key tool that is needed to understand China from the perspective of history.

The idea that China has always been entangled in the world is one that historians of China now generally recognize. In taking this approach, I write simply as part of my generation. The idea of China as a Great State, by contrast, is new and largely my own. The inspiration for this idea goes back to my mentor Joseph Fletcher, though the credit for bringing me across the threshold of this idea must go to my colleague Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene. Perhaps the strongest prod, though, has been the burden of my own experience. In my twenties, for reasons I have never fully fathomed, I decided to study China. I thought that if I examined the far side of the world, I might make better sense of my own; but then China asserted its own questions, and I wanted to answer those. In those days, most of the frail bridges between China and the world had been swept away. I thought they needed to be rebuilt. Here in the twenty-first century, two remain still to be built. One is the bridge between the China of history and the China of now. The other is between China today and a world that has become increasingly troubled by its expansive presence. This book is dedicated to working on that first bridge in the hope that, by encountering China as it was, we might be in a better position to see China as it is.