A VISION SO NOBLE

John Boyd, the OODA Loop, and Americas War on Terror

Daniel Ford

Warbird Books 2013

Contents

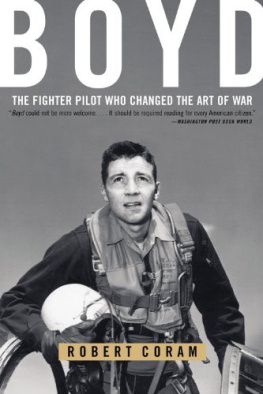

John Boyd, well groomed for a change

The Mad Major

JOHN BOYD WAS ARGUABLY THE MOST IMPORTANT American military thinker since the late-19th-Century sea power theorist, Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan. Best known for his formulation of the OODA Loop as a model for competitive decision making, Colonel Boyd left his mark as well on air combat tactics, maneuver warfare, and what we now call fourth-generation warfare. On no branch of the service was his influence greater than on the U.S. Marine Corps. From John Boyd, wrote General Charles Krulak, then the Marine commander, we learned about competitive decision making on the battlefield compressing time, using time as an ally.

An aggressive man, Boyd naturally favored the offense, as exemplified by the blitzkrieg or lightning war advocated by the Chinese master Sun-tzu, the German tank commander Heinz Guderian, and the British partisan leader T. E. Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia. Boyd was less interested in defensive tactics, though in his culminating, fifteen-hour brief, A Discourse on Winning and Losing, he did dwell at some length on the problem of what he called counter-guerrilla operations.

Boyd died in 1997, after Osama bin Ladens declaration of war against the United States, but before Americas trauma of September 11, 2001, in which the al-Qaeda leader set us on a course to our subsequent difficulties in Afghanistan and Iraq. Given another ten years of life, Boyd certainly would have addressed the question I attempt to answer here: How to fight the War on Terror? How should we have orchestrated our response to the al-Qaeda attacks or, in the parlance of the 21st Century: how would John Boyd have us fight a fourth-generation war?

BOYD WAS BORN IN THE HARDSCRABBLE town of Erie, Pennsylvania, in 1927. His father died when he was three, at the onset of the Great Depression, and he was brought up by his widowed mother, who worked three jobs to rear him and four siblings, one of whom was stricken by polio and another by schizophrenia. Toward the end of World War II, young Boyd enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces but was rejected for flight training because of low aptitude. Instead, the Army put him to work as a swimming instructor in occupied Japan.

Discharged in 1947, he enrolled as an engineering student at the University of Iowa. It wasnt a success. Academically, as Grant Hammond tells us in his 2001 biography, The Mind of War, Boyd was competent but inconsistent, undisciplined, and occasionally just not interested.

Transitioning to jet fighters, Lieutenant Boyd was just as aggressive. I had to bend the shit out of that airplane, he once boasted of his mock combat with flight instructors and fellow students. The Air Force did have rules, of course, but Boyd preferred to make his own.

Oddly, for a man often called Americas greatest fighter pilot, Boyd was never credited with an air-to-air victory over an enemy aircraft. He reached Korea in March 1953, four months before the armistice was signed, and not time enough to accumulate the thirty missions that would qualify him as a shooter, instead of a wingman tasked with guarding his flight leader.

Postwar, Boyd was assigned to the USAF Fighter Weapons School at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, first as a student, then an instructor. He was a demanding teacher. If the guy really wants to learn and has some problem, as he explained his system in later years, you do not have to give him the 2x4. But if the guy has an obstruction i.e., had an overly high opinion of his abilities I would cut his balls off in 10 seconds. The castration would take the form of an air-to-air humiliation. Boyd began the dogfight as he usually did, with the student directly behind him on his six, as pilots say, the six oclock position being the most advantageous for the attacker and in under forty seconds reverse their positions, meanwhile shouting Guns, guns, guns! to let the student know that in the real world he would have been a dead man. In this manner he earned the nickname of Forty Second Boyd.

Boyd loved the freedom he found in aerial combat. And he too was learning. In the air with his students or a fellow instructor, or a challenger from another airbase he made one of those connections for which he would become famous. I had a degree in economics, as he recalled toward the end of his life. What a fighter pilot did in the clear Nevada air, he realized, was not all that different from what John D. Rockefeller had done with Standard Oil, or E. H. Harriman with the Union Pacific railroad. This is like 19th Century capitalism in the sky! he exulted. All were doing is free-booting. Were buccaneers. This is fantastic. We can do whatever in the hell we goddamn please. Those generals dont know what the hell were doing.

In an interview taped after he retired, Boyd describes that mock combat over the Nevada desert in terms that illuminate the unique way his mind worked:

I would see myself in a vast ball I would be inside the ball and I could visualize all the actions taking place around the ball [while] all the time of course I am maneuvering.... I could visualize from two reference points. When I was fighting air-to-air, I could see myself as a detached observer looking at myself, plus all the others around me.

Unusually, in an American military that believed in regular rotations, Boyd stayed at the Fighter Weapons School for six years, teaching a generation of American and foreign fighter pilots. Meanwhile, he changed the schools emphasis from gunnery (how to shoot) to tactics (how to prevail). He also taught himself calculus at night, and he dictated what would be his only significant print publication. The mimeographed Aerial Attack Study was the first attempt to explain air combat maneuvers as an interlinked series of moves and countermoves, one flowing logically into the next.

And note the title: Aerial Attack Study. Boyd expected his pilots always to play offense.

Energy Manuverability

Typically, if a peacetime Air Force captain hopes to be promoted, he must first earn an advanced degree. But when the education furlough came to John Boyd, he opted instead to study for a second bachelors degree, this one in industrial engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. It was in Atlanta, as a 35-year-old father of five, that a classmate happened to ask what it was that a fighter pilot did when he met an enemy aircraft. The questioner was Charles Cooper, an undergraduate little more than half Boyds age. They were both taking a course in thermodynamics, so Boyd used their common background to explain that, just as a generator can transform mechanical motion into electrical energy, so can a pilot transform higher altitude into greater speed or either one into the ability to maneuver.

Then it hit me, as he told the story years later; Jesus Christ, wait a minute!I can look at air-to-air combat in terms of energy relationships. I can lay out equations. I can do it formally now. He spent the rest of the night laying out the equations, and when he was done he had the basis for what would become known as his Energy Maneuverability theory, which the military inevitably shortened to E-M. As he later explained:

Maneuverability means altitude, airspeed, and direction, in any combination. You can use energy to measure those changes. In other words, quantify. Obviously, you can do it for two competing airplanes and some numbers are higher for one airplane over the other.