2001 by Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

Editing by Lorraine Atherton

Production editing by Ruth Spiegel

Design by Janice Wheeler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hammond, Grant Tedrick, 1945

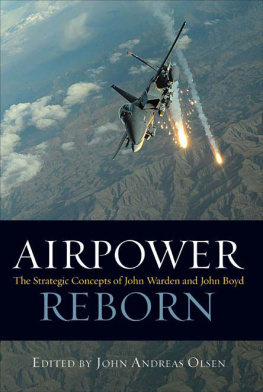

The mind of war : John Boyd and American security / Grant T. Hammond.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56098-941-7 (alk. paper)

1. Boyd, John, 19271997. 2. Fighter pilotsUnited StatesBiography. 3. United States. Air ForceBiography. 4. Military art and scienceUnited StatesHistory20th century.

5. Fighter plane combat. I. Title.

UG626.2.B69 H35 2001

358.43092dc21

[B] 00-046311

An Electronic release (eISBN: 978-1-58834-364-2) of the original cloth edition

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the author. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

The views expressed in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Air University, the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any portion of the U.S. government.

www.smithsonianbooks.com

v3.1

To the men and women of the United States Armed Forces and especially the mavericks among them

Contents

Preface

This book began nearly a decade ago, in October 1991, when a colleague at the Air War College, Col. Ray Bishop, invited me to sit in on a session of a course he was teaching entitled Strategy beyond Clausewitz. A guest speaker would be lecturing the class, a retired Air Force colonel named John Boyd, and Ray thought I would enjoy hearing what he had to say. A recent addition to the Air War College faculty as a civilian academic, I had become jaded rather quickly by the seemingly endless array of colonels and general officers that someone thought had something significant to say. I acknowledged the invitation and muttered something about trying to make it. Ray said, No, Grant. Hes not like the others. You really need to hear him. I promise you will find it rewarding. So I heard John Boyds briefing, A Discourse on Winning and Losing, for the first of many times.

Ray was right. It was clear that this was no ordinary former Air Force officer, nor an ordinary mind. A brusque, articulate, often profane, gravel-voiced man, Boyd moved catlike about the room during the briefing, his eyes sparkling. He stalked ideas and flushed them out of his audience. He led us to discover insights and connections before he had to tell us. He ranged widely over history, politics, technology, and economics. He could discuss by book, chapter, and section Sun Tzus Art of War and Carl von Clausewitzs On War with equal aplomb and in fine detail. He appeared to be as knowledgeable about guerrilla warfare as air-to-air combat. I remember thinking that was an odd combination of interests and expertise. How could this be?

Boyd was entertaining, demanding, provocative, and stimulating. After the second day of hearing and talking with Boyd, I asked Ray Bishop if he had published anything or if anyone had written about him. Ray said no, not that he knew. I remember commenting that someone should do a book about this guy and his ideas. Ray said, Why dont you? I said I was far too busy with other projects and wasnt into biographies in any event. Within a few months, however, all that had changed. After reading through The Green Book, the 327 pages of briefing slides that constitute A Discourse on Winning and Losing, I was hooked. I had to learn more about these ideas and interpretations and how Boyd had come up with them.

So began a relationship that has been a transforming one. I dont agree with Boyd on all topics, and I found his sheer level of intensity difficult to take at times, but I valued our association and have profited greatly from it. What I have read and learned about how to read and learn, about a variety of subjects, some well beyond my ken, has changed me forever. I learned about the mechanics of flight and aircraft design, evolution, mathematics, bits of military history, theoretical physics, the workings of the brain, philosophy, industrial production, leadership, decision-making theory, time, Japanese management theories, and John Boyds trinity of Gdel, Heisenberg, and the second law of thermodynamics. Reading the many works in Boyds Sources for A Discourse (which he deemed valuable and essential to the evolution of his thought) was an education itself, equivalent to another graduate degree. For that I and many others owe John Boyd a debt we can never repay.

Writing a biography, the story of another persons life, is a difficult task because of the moral imperative one feels to get it right. This may be the most anyone, including longtime friends, will ever know of John Boyd and his ideas. To be accurate in the portrayal of each is a heavy responsibility, but writing a biography, personal and intellectual, of a living person is even more difficult, as it becomes part of a continuing dialogue and as such is never finished. To do so when one enjoys the learning process, is sympathetic to wide-ranging syntheses, and finds the impact of the process transforming makes it more difficult still. Hence, writing this book has been an effort to hold an inquisition with myself. That is not an easy task, but I have attempted it anyway and hope the results will weather the scrutiny of others and that the product is seen as useful. Boyd and his ideas are important, however flawed my chronicle of them may turn out to be. Sadly, it was the occasion of his death that made the final investigations possible and forced me to close the dialogue.

John Boyd was a larger-than-life character who touched many people and made waves in the military system over several years, both in uniform and out. He and his exploits have taken on a legendary quality. Stories about him have been embroidered over the years. Some were told by him, some by others, but all have become jumbled and may stray from the truth. Most were told by fighter pilots, who like Southerners enjoy the telling of the story as much as the story itself. (Like the Irish, who represent another oral tradition, fighter pilots also view writers as failed conversationalists.) Thus what is recorded here is the lore and the legend of John Boyd, corroborated where possible, taken from printed sources and interviews. Some anecdotes and interpretations are impossible to verify. The participants are either lost or dead, the stories from Boyd alone or reiterated by so many others so often that they have become the record, true or not. This book deals mainly with Boyds ideas and their effect on others. It is less a validated record of Boyd than it is an intellectual biography. In that the stories are a part of the image that was Boyd, they are a part of this chronicle, but I cannot vouch for the veracity of all of them in their finer details. That some myths may thus be perpetuated may be regrettable, but it is also the stuff of which legends are made.

Boyd is known to a relatively small coterie of people. His name is hardly a household word. He attained success in his career on a number of issues, in a number of fields. He was a major contributor on air-to-air tactics, an aircraft designer, a military strategist, a bureaucratic in-fighter, a defense reformer, and a fighter pilot of great renown. He did not seek to capitalize on his considerable talents, his access to important people, or the value of his ideas. Others have chronicled portions of his life, his ideas, and impact. Jim Burtons