CONTENTS

For Becky

Ellis calls his book a cultural history, but it is much more The Coffee-House is everything it should be careful, intelligent and embodying the spirit of its subject by being written for the digestion of the general public. It contains the perfect recipe of scholarship, stimulant and froth Ophelia Field, Sunday Telegraph

This is a convincing and meticulous read, building an intriguing and engrossing picture of coffees role in British society a close examination of how particular rooms shaped the British identity Jonathan Myerson, Independent on Sunday

This readable and scholarly account of an important and curiously neglected phenomenon. Rich in evocative details (our forebears took their coffee black, strong and bitter, a brew redolent of stewed prunes, burnt beans and soot) and strong on social, political and economic context, The Coffee-House is a book for the coffee-lover and historian alike Sarah Burton, Spectator

Elliss sober, rigorous narrative lucidly dovetails the political with the cultural, and is particularly engaging as it charts the convulsions of England through its early modernization Ellis unpicks the ideologies that have contributed so importantly to our entrenched beliefs in freedom of speech and in our political constitution Kate Colquhoun, Daily Telegraph

He circles his subject, elegantly and thoughtfully investigating the cultures political, literary, financial that the rituals of the coffee house have helped to shape Norma Clarke, TLS

Markman Ellis studied at the universities of Auckland and Cambridge, and is now Professor of Eighteenth-Century Studies at Queen Mary, University of London. He has published books on the sentimental novel, and on gothic fiction, and has written on many eighteenth-century topics, including georgic poetry, slavery and travel writing.

ILLUSTRATIONS

The Art Archive:

Corbis:

Getty Images:

Guildhall Library, Corporation of London:

The Bridgeman Art Library:

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, 738.0.3 (1738 etching and engraving, 26.5 20.8 cm., plate):

PREFACE

The Conversible World

Caffeine is the most widely used drug in the world, exceeding all other common drugs including nicotine and alcohol. The value of the coffee traded on international commodity markets is surpassed only by oil. Yet for most of human history, coffee was unknown outside a small region of the Ethiopian highlands. Coffee itself has been consumed in Europe only in the last four centuries. There is no coffee in the Torah, or the Bible, or the Koran. There is no coffee in Shakespeare, Dante or Cervantes. After initially being recognised, in the late sixteenth century, by a few sharp-eyed travellers in the Ottoman Empire, coffee gained its first foothold in Europe among curious scientists and merchants. The first coffee-house in Christendom finally opened in London in the early 1650s, a city gripped by revolutionary fervour. In this sense, coffees eruption into daily life seems to coincide with the modern historical period.

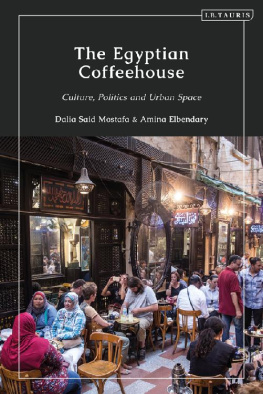

A coffee-house exists to sell coffee, but the coffee-house cannot simply be reduced to this retail function. In his Dictionary, Samuel Johnson defined a coffee-house as A house of entertainment where coffee is sold, and the guests are supplied with newspapers. More than a place that sells coffee, Johnson suggests, a coffee-house is also an idea, a way of life, a mode of socialising, a philosophy. This book seeks to explain how the coffee-house came to have these connotations, how a simple commodity rewrote the experience of metropolitan life. Yet the coffee-house does have a vital relationship with coffee, which remains its governing symbol, lending it connotations of alertness, sobriety and volubility. These convivial and conversational associations grant the coffee-house a unique place in urban life and manners, in sharp contrast to its alcoholic competitors.

The story of the coffee-house is a historical narrative, in which the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries take central stage. In the hundred years after the first coffee-houses opened in London, they came to be ubiquitous features of the modern urban landscape, indispensable centres for socialising, for news and gossip, and for discussion and debate. In the coffee-house, men learnt new ways of combinational friendship, turning their discussions there into commercial ventures, critical tribunals, scientific seminars and political clubs. As the following chapters explain, the legacy of the early coffee-house is not simply to be found in Starbucks and other modern retailers of coffee, but also in the stock market, in insurance companies, in political parties, in the modern regard for public opinion, in the institutions of literary criticism, in the research cultures of modern science and in the Internet. As many commentators have noted, the coffee-house has provided many websites with a powerful metaphor for all kinds of collaborative intellectual enterprise. From the cyber-cafs of the 1990s, to the wi-fi enabled coffee-house of the new century, the overlap between the coffee-house and the information age has never seemed so exact.

The history of the coffee-house is not business history. The early coffee-house has left very few commercial records. But historians have made much use of the other kinds of evidence that do exist. In the archives of government, a rich seam of evidence details the reports of state spies and ministers on conversations heard and alleged in coffee-houses. Further evidence is found in early newspapers, both in their advertisements and news reports. Legal records, such as probate inventories, parish registers and property records, also contribute to this story. The eminent diarists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, including Samuel Pepys, Robert Hooke and James Boswell, testify to the centrality of the coffee-house in the social life of the period. This book makes use of all these kinds of evidence.

In depicting the life-world of coffee-houses, however, much of the most compelling testimony is literary. The variety and nature of the coffee-house experience have made it the subject of a huge body of satirical raillery, jesting humour and deliberately partisan misrepresentation. Yet satire rarely offers such a simple picture. It is in the nature of satire to exaggerate what it depicts, to amplify folly and vice, and to cast its material in the most brightly hued language. In this book the coffee-house satires are considered as works of literature as well as historical evidence: these low and vulgar satires are not a simple indictment of coffee-house life, but part of their conversation, one voice in the ongoing discussion of the social life of the city.

A note on dates

Until the reform of the English calendar in 1753, the civil year (used in official and legal documents, for example) began on 25 March, so that, for example, 31 December 1675 was followed by 1 January 1675. Many people wrote dates between January and 25 March so as to indicate both dates, thus the date which is 14 February 1676 in modern notation was written 14 February 1675/76. This book has silently followed modern practice, by writing dates between 1 January and 25 March according to modern notation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am very grateful to the following people for their invaluable advice on the project at various stages: Becky Beasley, Richard Hamblyn and Anne Janowitz, as well as John Barrell, Ben Buchan, Marilyn Butler, Georgina Capel, Vincent Caretta, Emma Clery, David Colclough, Richard Coulton, Elizabeth Eger, Charlotte Grant, Gavin Jones, John Mitchinson, Miles Ogborn, Chris Reid, Morag Shiach and Sue Wiseman.