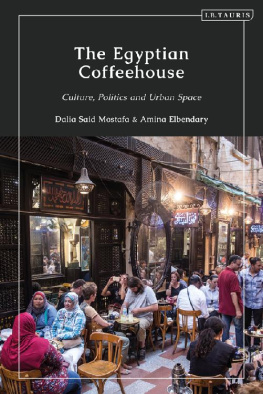

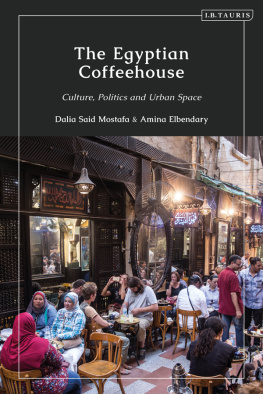

The Egyptian Coffeehouse

The Egyptian Coffeehouse

Culture, Politics and Urban Space

Dalia Said Mostafa and Amina Elbendary

Contents

Figures

Plates

Our heartfelt thanks and gratitude go to our friend and colleague Dr Solava Ibrahim (Anglia Ruskin University) who embarked with us from the start on this book project and contributed to the structure and key ideas which have been developed in the book. Solava could not continue this journey with us to the end because she went on maternity leave.

Special and sincere thanks also go to our friend and colleague Dr Michelle Obeid (University of Manchester) who was the first to advise us on including a photo-story and contributed some extremely useful ideas on the structure of

.

The support, appreciation and love of our families and friends over the past few years while working on the book made our writing journey enjoyable and pleasant: A big Thank You for the insurmountable love and care you have given us.

Special thanks are also due to photographer Adel Wassily whose pictures, specifically compiled for this book, have added an extra layer of value to the narrative.

Lastly, we are sincerely grateful to our interviewees in Cairo who agreed to contribute their time and wonderful stories about their favourite coffeehouses. Your passion for the Egyptian coffeehouses has been a true inspiration for us.

Introduction

A place for socialization and entertainment, the coffeehouse has long been associated with popular communal gatherings in both urban and rural Egypt. The coffeehouse is a social space which was created and shaped over the decades by the people themselves in their neighbourhoods, and on the cities squares and streets. It is a microcosm of the larger Egyptian society with its history of multiculturalism and great diversity. In a sense, the Egyptian coffeehouse subverts archaic forms of institutionalization and social exclusion. Hence, it has occupied in the popular imagination a sphere that is replete with new ideas, stories, memories and social networks. It is no surprise then that representations of the coffeehouse have taken countless forms in Egyptian literary works, films, songs, photographs, radio and television programmes and drama shows. Historically, the coffeehouse has also played a key role in political mobilization, as well as being a place where the unemployed could access job opportunities through meeting potential employers. Despite the coffeehouses cultural centrality and sociopolitical importance in Egypt, academic research and publications on its significance remain sparse.

This volume aims to fill this academic gap through analysing, for the first time in a full study in English, the importance of the coffeehouse as an urban phenomenon which has cultural, historical, economic and political implications in the contemporary Egyptian society especially in the aftermath of the 25 January 2011 revolution. The main objectives of the volume can be summarized as follows: to theorize and unpack the role and influence of the coffeehouse as a significant feature of contemporary Egyptian life and social relationships; to illustrate the ways in which the coffeehouse has been depicted in the Egyptian cultural field, particularly in literature, cinema and song; to study the political, spatial and economic dynamics of the coffeehouse as an integral public space in the life of Egyptians; to demonstrate through highlighting specific examples of traditional coffeehouses in Cairo and Alexandria the various roles they play in these cities; and finally to offer some indicative public views of the coffeehouses role through open-ended interviews with six residents of Cairo.

In Egypt, there are two widespread types of the coffeehouse (or ahwa as pronounced in the Egyptian vernacular): the first is the ahwa baladi (the traditional caf /coffeeshop) which is found in almost every neighbourhood across the country and usually dominated by mens presence. The second type is the historical-cultural coffeehouse such as al-Fishawi in al-Hussein area in Islamic Cairo or the Naguib Mahfouz coffeehouse also in al-Hussein; or the well-known Caf Riche on Talaat Harb Street in downtown Cairo; or al-Horriyya coffeehouse in Bab al-Louq (off Tahrir Square); or the multiple European-style coffeehouses in Alexandrias downtown Raml area (e.g. Trianon, Delice and Elite). This latter type of the historical-cultural coffeehouse is open for both men and women of different backgrounds and age groups. The contrast in the history and architecture of coffeehouses such as al-Fishawi, on the one hand, and Caf Riche on the other, cannot be more fascinating as an indicator of the richness of the multifaceted architectural history of Egyptian cities. While al-Fishawi is immersed in Islamic Cairo (the old city) with its notable bazaar culture and spiritual ambience, Caf Riche was founded in the early years of the twentieth century during the colonial era in the modern quarter of khedival Cairo (the new city), inspired by European architecture. The photographs which are included in this volume display some of these historical and architectural differences which are perceived in themselves as key signifiers of cosmopolitan culture in Egypt.

Next page