Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

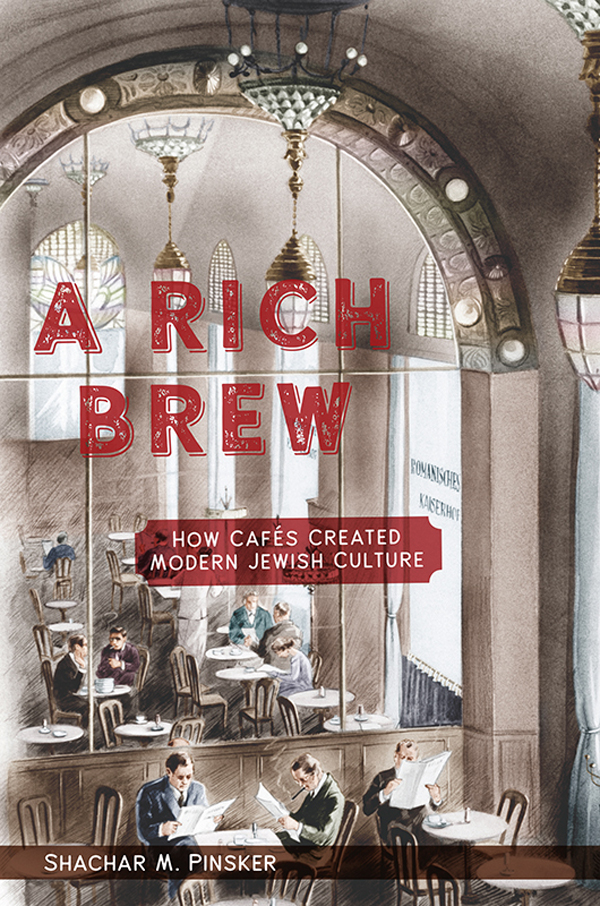

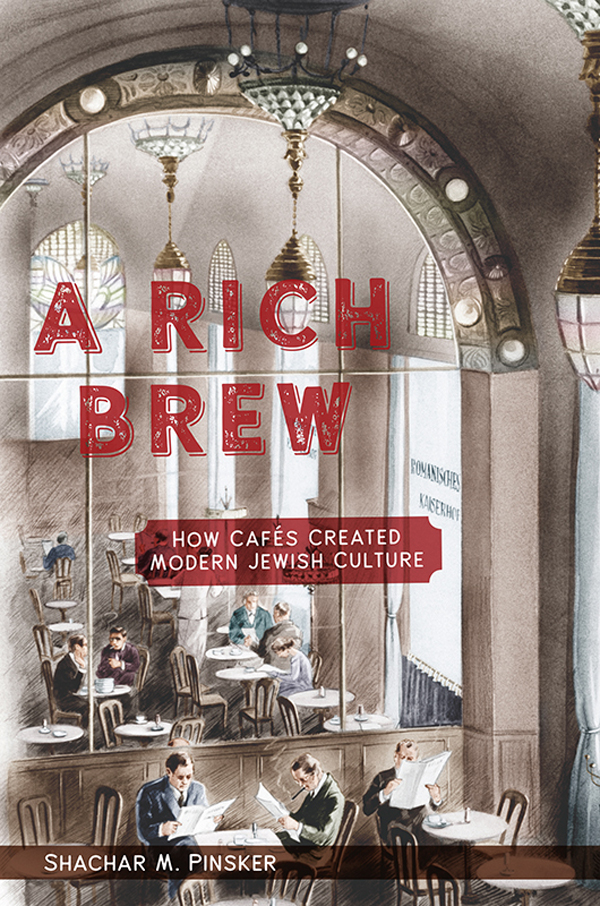

A RICH BREW

A Rich Brew

How Cafs Created Modern Jewish Culture

Shachar M. Pinsker

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2018 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pinsker, Shachar, author.

Title: A Rich brew : how cafs created modern Jewish culture / Shachar M. Pinsker.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017034136 | ISBN 9781479827893 (cl : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: JewsSocial life and customs19th century. | JewsSocial life and customs20th century. | JewsIntellectual life19th century. | JewsIntellectual life20th century. | CoffeehousesSocial aspects.

Classification: LCC DS 112 . P 64 2018 | DDC 305.892/4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017034136

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

This book is dedicated to my wife, Amanda Fisher, and to my dear friend David Ehrlich.

CONTENTS

A NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION AND TRANSLATION

Modern Jewish culture is multilingual, and the sources I draw on, cite, and analyze in this book are in Hebrew, Yiddish, German, English, Russian, and Polish. Three of these languages do not use Roman characters, and this fact creates a major problem, since there are various norms and variations. Creating a perfectly consistent system of transliteration in English across the various languages is doomed to fail, despite the best intentions. The purpose of transliteration is to assist readers of English who are not familiar with the original languages, and this principle takes precedence over the desire for consistency. Nevertheless, I try to be consistent within each language. For Hebrew, I follow the Prooftexts journal system of Romanization, which is a modified, simplified version of the Library of Congress system. For Yiddish, I follow the YIVO system. For Russian, I follow the Library of Congress system. For proper names of people and places, I try to retain the form most familiar to readers of English.

When texts from foreign languages have been translated into English, I use and cite these published translations. Otherwise, translations are mine, with much-needed assistance from experts on languages in which I am not proficient.

Introduction

The Silk Road of Modern Jewish Creativity

In January 1907, a young and handsome Jewish man took the train from his small hometown of Buczacz to the city of Lemberg. The nineteen-year-old was an aspiring Yiddish and Hebrew writer by the name of Shmuel Yosef Czaczkes, better known to us as S. Y. Agnon, the winner of the 1966 Nobel Prize for literature. The trip to Lembergthe provincial capital of Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian Empiretook him only a few hours, but it changed his life. Shmuel Yosef was traveling in order to become an assistant to Gershom Bader, an older journalist and writer of fiction who wrote in Hebrew, Yiddish, German, and Polish. Bader had established a Hebrew daily newspaper with the name Et (Time) and invited Shmuel Yosef to assist him. This was an opportunity he could not refuse.

Lemberg in the early twentieth century was renowned for its coffeehouses. Bader and other Jewish writers frequently socialized in cafs; sometimes they would also write or edit there, using the caf table as their working desk. The polyglot enthusiasm of Lembergs caf, an institution held together seemingly by little more than the desire for coffee and conversation, made a strong impact on him.

A little more than a year later, in April 1908, Shmuel Yosef traveled to Lemberg once again. This time, he had decided to leave his parents home and migrate to Palestine in the Ottoman Empire. On his way there, he stopped in a few European cities. First, he arrived at Lembergs railway station and went directly to the caf to bid farewell to his old friends and to meet new ones. After his visit in Lemberg, Shmuel Yosef traveled to Krakw and then to the capital city Vienna, where he met other Jewish intellectuals in still more Kaffeehuser . At the end of this trip, he arrived at the Arab port of Jaffa on the Mediterranean coast. He lived in Jaffa for a few years, frequenting Arab-, German-, and Jewish-owned cafs, and became part of a small Jewish intellectual and literary community. He made a name for himself as a Hebrew writer and changed his last name from Czaczkes to Agnon. Then in 1912, he journeyed back to Europe, this time to Berlin, where he joined a thriving Jewish cultural community that again met frequently in cafs. He spent the tumultuous years of World War I in Berlin before leaving Germany in 1924, traveling to Mandatory Palestine and eventually settling down in Jerusalem. In the 1930s, many Jewish migrants arrived there after fleeing Nazi Germany and Austria. As they found their way beyond the trauma that had forced them out of their homes, many of the refugees opened cafs, becoming part of the growing local intellectual and literary community, which had so inspired Agnon.

Agnons journey took him to many cities and to many cafs. He traversed much of the route that we will follow in this book. But Agnons caf-laden path also tells us something about Jewish modernity writ large. These coffeehouses, way stations for Jewish intellectuals on the move across Europe and beyond, were central to modern Jewish creativity. In order to begin to contemplate the role of cafs in the development of Jewish modernity, we can turn to Agnons fiction, to texts such as the novel Tmol shilshom ( Only Yesterday ), which he wrote in Jerusalem when he was a middle-aged man. In the novel, Agnon used episodes from his own biography to depict the life of Yitzak Kumer, a young and nave protagonist. In one of the early chapters of the novel, Kumer travels to Lemberg, and upon arrival at the train station, he hurries to one of the local cafs. Why the coffeehouse? What, after all, is so important about a local caf that Kumer feels that he must go there as soon as he arrives in the city? Agnons narrator explains:

A big city is not like a small town. In a small town, a person goes out of his house and immediately finds his friend; in a big city days and weeks and months may go by until they see one another, and so they set a special place in the coffeehouse where they drop in at appointed times. Yitzak had pictured that coffeehouse as the most exquisite place, and he envied those students who could go there any time, any hour. Now that he had arrived in Lemberg, he himself went to see them.

A few hours later, Kumer finds himself

standing in a splendid temple with gilded chandeliers suspended from the ceiling and lamps shining from every single wall, and electric lights turned on in the daytime, and marble tables gleaming, and people of stately mien wearing distinguished clothes sitting on plush chairs, reading newspapers. And above them, waiters dressed like dignitaries holding silver pitchers and porcelain cups that smelled of coffee and all kinds of pastry.