One of our defining features as humans is our use of the material we find in the natural world. Since prehistoric times, we have made pigments, tools, foodstuffs, pottery, bricks, medicines, perfumes and jewellery, moulding the matter around us into new physical and chemical forms. We did it long before we had any concept of chemistry as a science.

Making medicines has been an important spur to progress in chemistry for millennia. Here, 13th-century Persian pharmacists are at work.

Adventures in pre-chemistry

Our earliest ancestors began their exploration of pre-chemistry when they discovered the transformative power of fire, or ground minerals and plant matter to make pigments and medicines. These first adventures were doubtless haphazard and random; they would have revealed some substances that were useful, some that were not, and probably some that were downright dangerous.

Early humans messing around with matter and its properties exploited the riches of the natural environment in a way that involved changing them to uncover new properties. This is the very essence of chemistry: to discover the ways in which matter can be transformed and use them to your advantage. We can easily imagine a forebear from the Paleolithic period poking a stick in the fire and finding that he or she could then make a mark on the rock with the blackened end, or that juicy, chewy, fibrous meat becomes easier to eat and has a different flavour after the application of fire. Perhaps dyes and pigments were first discovered accidentally, when squashed plant material left a stain. Without curiosity, these serendipitous accidents would have led nowhere. Inquisitive humans who heated lumps of earth with sparkly seams running through them to extract the metal, or fashioned clay from the mud at their feet into useful shapes, were the first proto-scientists, the first pre-chemists. They didnt know or need to know how the transformation of matter worked or why it changed properties they simply explored and exploited their discoveries in ways that became essential to human culture and civilization.

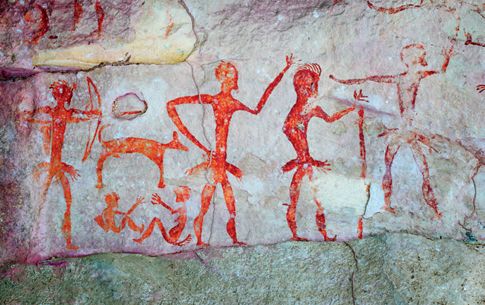

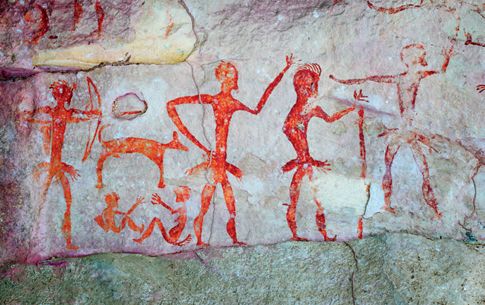

Neolithic cave paintings made 2,5004,000 years ago in Thailand using a bright red pigment.

Chemistry of colours

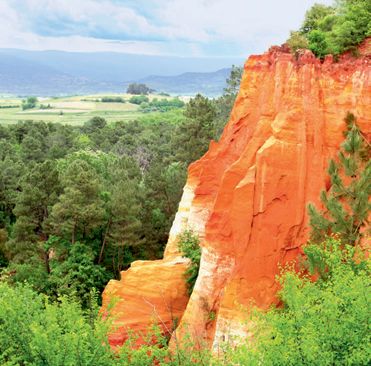

People began to decorate their environment by painting the walls of caves they lived in a very long time ago. The earliest evidence of pigment-making dates from 70,000100,000 years ago in the Blombos Cave system in South Africa. Here archaeologists found two ingredients for making paint ochre and animal bones that artists would simply grind together. Ochre is a naturally occurring mineral consisting of silica and clay and an iron-rich substance called goethite, which gives it its yellow to orange-brown colour. Other prehistoric paints were made from carbon (burnt wood or bones) for black, chalk (calcite, calcium carbonate) for white, and mineral pigments including umber (a natural mixture rich in iron and manganese) for browns and creams. Sometimes mineral pigments might be found in clay that could be applied directly to a surface, like crayons. Otherwise pigments were ground and mixed with water, plant juices, urine, animal fat, egg white or some other carrier that would evaporate or solidify after the mix had been painted on to the wall. It seems that the earliest reason for mining rock was to extract mineral pigments for painting on cave walls or for body decoration, and people travelled considerable distances to collect them.

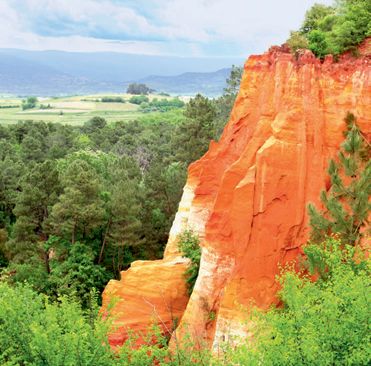

Ochre from cliffs near Roussillon, France, has been used since prehistoric times; its modern processing to make an indelible dye dates from 1780.

Pigments used to dye cloth or to adorn the body were often plant-based. Some of those were not permanent and would wash out in water, so a bit of experimentation would have been needed to discover which were fast and which were not (and not might have been an advantage in the case of body decoration).

Powdered umber, a mineral pigment from Umbria in Italy.

From Paleolithic to pots

By the time of the Neolithic period, around 10,000 years ago, people had begun to settle in one place and to farm the land. They soon developed pottery and began working with metals. Both involved processing materials using heat and sometimes mixing them together to change their properties.

Kilns for firing pottery first appeared around 6000 BC. Coloured glazes, to give permanent colour to pottery, were first used around the 4th or 3rd millennium BC. They were made by mixing minerals with sand and heating them to melting point. Such glazes may well have been discovered accidentally, as copper smelting was carried out in clay furnaces; a blue glaze could easily have appeared on stones or clay, as copper formed compounds on the surface.

Clay was also used to make bricks, and either left to dry in the sun or baked hard in an oven. The clay was often mixed with straw, which made it stronger.

Plaster, pigments and shells (for eyes) were used to recreate the head of a dead person in the earliest known ancestor veneration practices of the Middle East, about 7000BC.

GLASS FROM GLAZES

Glass was first developed as a glaze for pottery around 3500 BC in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq). A thousand years later, it was produced as a substance in its own right. The chief ingredient of glass is silicon dioxide, which is abundantly available as sand. Any civilization with a beach can make glass, and they did the Ancient Greeks and Romans both made exquisite glassware. The molten glass could be formed around a mould, blown or cast, and was easily mixed with minerals to produce vibrant colours. Glass is not especially robust, but is exceptionally hard and doesnt corrode or dissolve, which made it useful for later forays into chemistry.

The blue-green colour of Egyptian faience is produced by copper pigments.

Metals and mining

The very earliest activity in proto-chemistry left few traces. It takes little effort and no special tools to pick plants and crush them together. Working with clay is easy in areas where clay can be scooped up by hand from riverbeds. The results, painted or dyed artefacts and pottery, dont usually last long. When people learned to fire their pottery in a furnace, rather than drying it in the sun, it lasted longer but was still fragile. Much of the surviving early pottery was deliberately preserved, as grave goods.

Working with metal is more complex, and produces more durable objects. It takes physical work to extract metal and to fashion it, generally requiring high temperatures and some peril. Mines and smelting leave evidence for archaeologists to find.