2001 by the Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Glines, Carroll V., 1920

Around the world in 175 days: the first round-the-world flight/Carroll V. Glines

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-56098-967-X (alk. paper)

1. Flights around the world. 2. United States. Army. Air Corps. 3. World records.

I. Title: Around the world in one hundred seventy five days. II. Title.

TL721.U6 G55 2001

629.1309dc21 2001020583

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available

A full subject index is included in the print edition.

ISBN: 978-1-944466-02-2 (ebook)

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works as listed listed in the captions. The Smithsonian Institution Press does not retain reproduction rights for illustrations individually or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

v3.1

CONTENTS

Foreword

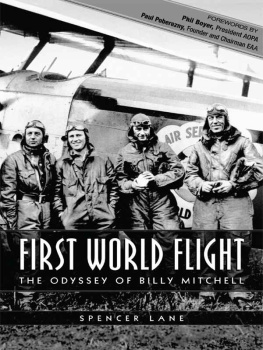

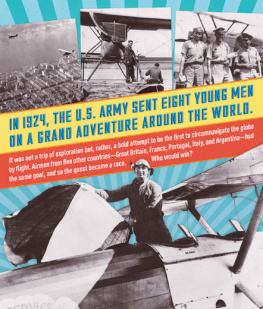

The 1924 flight around the world by the Air Service Douglas World Cruisers was one of the most important events of the Golden Age of Flight. While Charles Lindberghs famous solo transatlantic flight in May 1927 captured the imagination of the world, the flight of the World Cruisers had further importance in many ways.

The 1924 flight of 26,000 miles was far more ambitious, calling upon the resources of the Air Service, the U.S. Navy, the State Department, and many other agencies to make it possible. It was this concerted effort that made the flight so important, for it demonstrated on the one hand how difficult such a journey was, and on the other, how it was possible to solve the problems with sufficient foresight and effort. As impressive as the flying and navigation feats were on the World Flight, the logistics effort was even greater. It created a pattern, a modus operandi, for Air Service operations that were passed on, first to the Air Corps, then to the Army Air Forces.

The Douglas World Cruiser was basically a much modified version of the very successful DT-2 that set a number of records for its class and was used in a variety of roles by the U.S. Navy. Of the original four aircraft that began the historic flight in April 1924, two survive. It has been my privilege to have had a close relationship with both the Chicago and the New Orleans.

The Chicago was restored at the National Air and Space Museums Silver Hill facility, which now bears the name of Paul Garber, the distinguished curator who accepted the Chicago for the Smithsonian Institution in 1925. In the ensuing years, it deteriorated and had to be restored for exhibition in the new National Air and Space Museum that opened in July 1976. Walter Roderick, a brilliant craftsman, was assigned the restoration task, working with his equally skilled friend, Ed Chalkley.

Walter was a quiet, intense person with unbelievable skills that he dedicated wholeheartedly to the restoration of the Chicago. Through Ed, he drew upon the expertise of the other craftsmen at Silver Hill as required, but the Chicago was strictly his baby and he restored it with a meticulous attention to detail that is still startling today. An example: Biplanes of the period often used cloth tape to run from rib to rib in the wings for strength and conformity. The tape in the Chicagos wings was pinked but it was pinked in a unique, nonstandard manner. Walter first made pinking sheers which duplicated the original tape pinking, then spent countless hours, personally pinking every inch of the hundreds of feet of cloth tape in the wings. He then carefully proceeded to cover his workmanship with fabric, knowing that it would probably not be seen for maybe fifty yearsbut also knowing that when anyone saw it again, he would know that it had been authentically copied from the original.

It was my task to supervise the installation of aircraft and I was pleased to give the Chicago the honor of being the first aircraft to be installed in the new National Air and Space Museum in the summer of 1975. Chalkley and Roderick were there to superintend its movement from the old Castle. We placed it on the second floor of the Milestones of Flight Gallery in the new building, an inspiration to us all.

It later fell to Ed and Walter to supervise the movement of the New Orleans from the Air Force Museum in Dayton to its new home in the Museum of Flying at Santa Monica. Although there was not enough time to give the New Orleans the same degree of restoration that had been lavished on the Chicago, the two men saw to it that it was moved safely, given a cosmetic touch-up, and then hung securely in the new museum.

Working with Ed and Walter, it was obvious that they were of the same stripe as the men who had planned and made the original flight. They planned meticulously, executed their work with care and distinction, and did the job with a minimum of fanfare. And when the Chicago was given its place of honor in the National Air and Space Museum, no one appreciated the work of Ed Chalkley and Walter Roderick more than Leigh Wade, a surviving pilot of the flight and a great American gentleman. With tears in his eyes, Leigh congratulated both for the genuine triumph of restoration. It was a moving moment, one that no one present has ever forgotten.

Walter J. Boyne, Former Director

National Air and Space Museum

Acknowledgments

This book is about the courageous effort put forth six years after World War I by the U.S. Army Air Service to have its planes encircle the globe and preserve for all time the honor of being first. The Air Service kept accurate records at every step of the mission from idea conception to eventual success. The official records and correspondence are in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and the U.S. Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama. Diaries of two participants are available at the U.S. Air Force Museum, Dayton, Ohio, and the U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs. Memorabilia, photographs, and personal artifacts from the flight are on display in several museums in the United States. The archives of the Mobil Corporation, known previously as the Vacuum Oil Company and now Exxon Mobil, contain information on its role in furnishing petroleum products and cooperation throughout the flight.

The National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Flying at Santa Monica, California, are, respectively, the final resting places of the Chicago and the New Orleans, two of the nations most distinguished aircraft. The manufacturer aptly designated them World Cruisers even before the flight. They rank with the Wright Flyer and the Spirit of St. Louis as representatives of the progress of fixed-wing aviation during its first quarter-century.

One of the foremost sources of personal reminiscences about the flight was the book written by the late Lowell Thomas, world famous adventurer, author, and radio/television commentator who was the flights official historian. He based his book on the personal narratives of six participants. His files containing the notes made during interviews with them are located at the Marist College, Poughkeepsie, New York. In order to preserve the immediacy and accuracy of the events they describe, I chose to use the stories as they appeared in the book,