bibliography

Aitken, Alexander, Gallipoli to the Somme, Oxford University Press, London, 1963.

Banks, Arthur, A Military Atlas of the First World War, Heinemann, London, 1975 and Leo Cooper, 1989.

Barrie, Alexander, War Underground, Spellmount, Staplehurst, 2000.

Beckett, Ian F. W., The Great War 19141918, Longman, Harlow, 2001.

Blond, Georges, trans. H. Eaton Hart, The Marne, Macdonald, London, 1965.

Bourdon, Yves, Mons, Augustus 1914, ASBL, Mons, 1987.

Brown, Malcolm, The Imperial War Museum Book of 1918, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1998.

Brown, Malcolm, The Imperial War Museum Book of the First World War, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1991.

General Staff, American Expeditionary Forces, Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty-One Divisions of the German Army which Participated in the War, WDD905, US War Office, 1920, and London Stamp Exchange, 1989.

Gilbert, Martin, First World War, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1994.

Gray, Randal, with Christopher Argyll, Chronicle of the First World War, 2 vols, Facts on File, New York, Oxford and Sydney, 1990.

Griffith, Paddy, Battle Tactics of the Western Front, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1994.

Griffiths, William R., The Great War, West Point Military History Series, Avery, Wayne, NJ, 1986.

Hammerton, J. A., A Popular History of the Great War, six vols., Fleetway House, London, 1934.

Holt, Tonie and Valmai, Battlefields of the First World War, Pavilion, London, 1993.

Keegan, John, The First World War, Hutchinson, London, 1998.

Lawson, Eric and Jane, The First Air Campaign, Combined Books, Conshohoken, PA, 1996.

Livesey, Anthony, Atlas of World War I, Viking, London and New York, 1994.

Lomas, David, First Ypres 1914, Campaign Series, Osprey, Oxford, 1998.

Macdonald, Lyn, 1914: The Days of Hope, Michael Joseph, London, 1987; Penguin Books, 1989.

Macdonald, Lyn, 1915: The Death of Innocence, Headline, London, 1993.

Macdonald, Lyn, Somme, Michael Joseph, London, 1983.

Macdonald, Lyn, They Called it Passchendaele, Michael Joseph, London, 1978.

Macdonald, Lyn, To the Last Man, Spring 1918, Viking, London, 1998.

Mackenzie, Compton, Gallipoli Memories, Cassell, London, 1929 and Panther, 1965.

Marix Evans, Martin, American Voices of World War I, Fitzroy Dearborn, London and Chicago, 2001.

Marix Evans, Martin, The Battles of the Somme, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1996.

Marix Evans, Martin, Passchendaele and the Battles of Ypres, Osprey, Oxford, 1997.

Marix Evans, Martin, Retreat Hell! We Just Got Here!, Osprey, Oxford, 1998.

Masefield, John, Gallipoli, Heinemann, London, 1916.

Mead, Gary, The Doughboys: America and the First World War, Allen Lane, the Penguin Press, London and New York, 2000.

Sheffield, Gary, Forgotten Victory, the First World War Myths and Realities, Headline, London, 2001.

Stallings, Laurence, The Doughboys: The Story of the AEF 19171918, Harper & Row, New York, 1963.

Strachan, Hew, The First World War, Volume I: To Arms, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001.

Strachan, Hew, Ed., The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1998.

Swinton, E. D., and the Earl Percy, A Year Ago, Arnold, London, 1916.

Terraine, John, Essays on Leadership & War, The Western Front Association, Reading, 1998.

Terraine, John, The Smoke and the Fire: Myths & Anti-Myths of War 18611945, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1980 and Leo Cooper, London, 1992.

Thomason, John W., Jr., Fix Bayonets! With the US Marine Corps in France 19171918, Charles Scribners Sons, New York, 1925 and Greenhill, London, 1989.

Trask, David F., The AEF & Coalition Warmaking 19171918, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence KS, 1993.

Turrall, R. Guy, Letters, unpublished.

Vaughan, E. C., Some Desperate Glory, Warne, London, 1981.

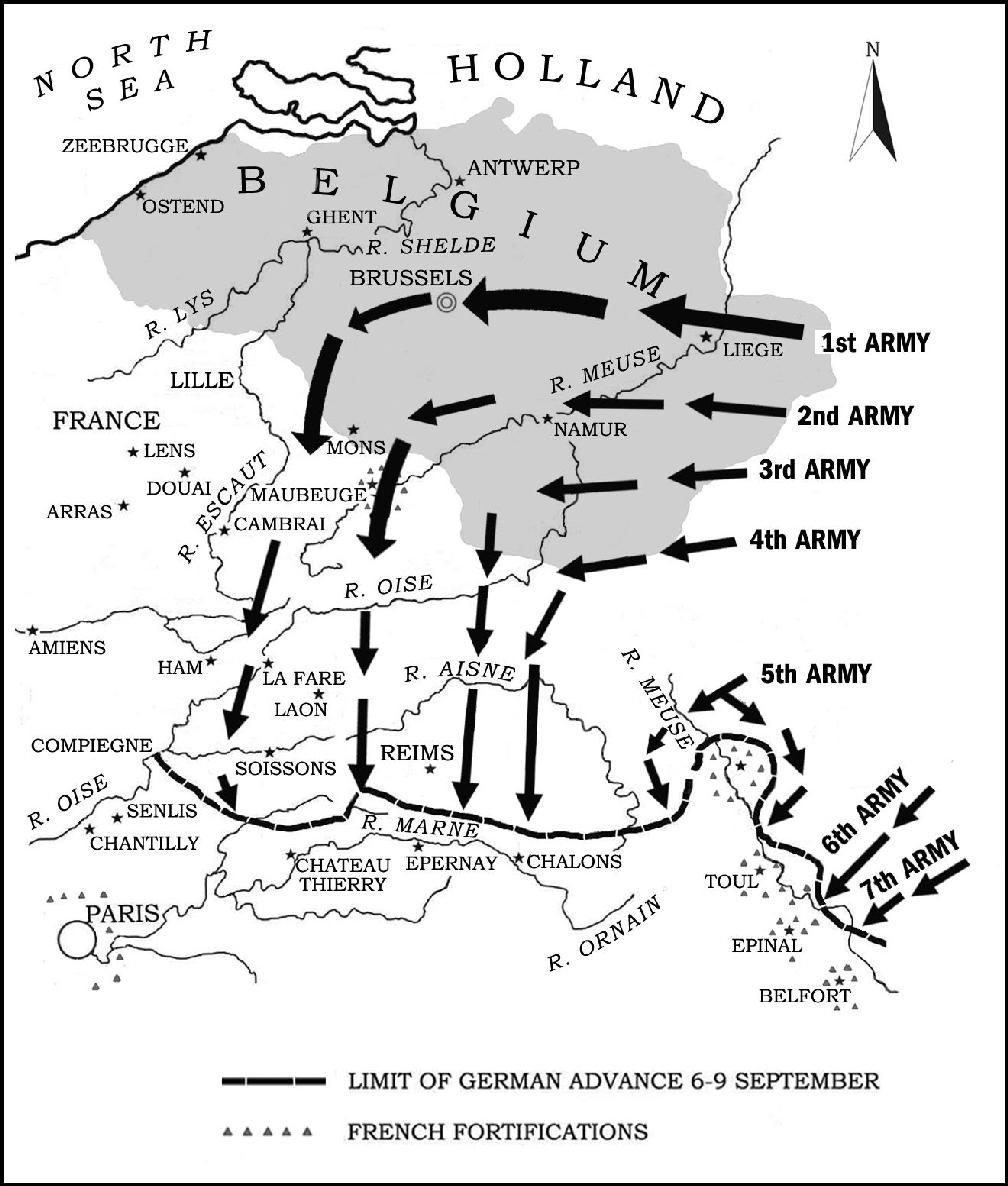

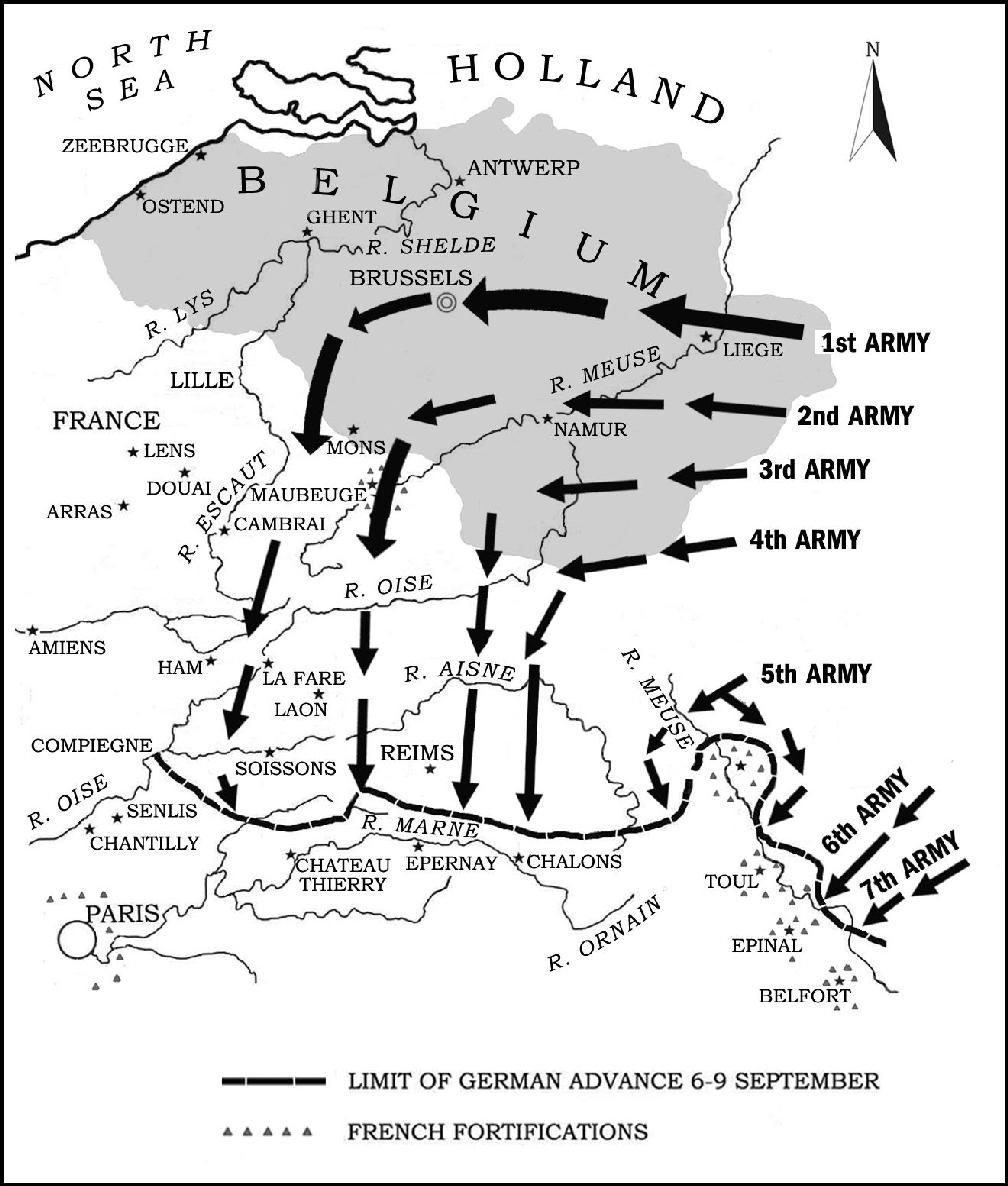

The German invasion of Belgium and France, AugustSeptember 1914

1

invasion

august 1914

On sunday, 28 June 1914, a temporary chauffeur got lost in a strange town. Count Franz Harrach had helped the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when he needed a car for a visit to the province of Bosnia-Herzegovina, between the Adriatic Sea and the independent, land-locked country of Serbia. The visit was not a success. On arrival the Archduke and his wife were attacked by a bomb-throwing member of the Black Hand, a Serbian nationalist secret society, as their procession drove along Appel Quay, the embankment of the River Miljacka in Sarajevo. The bomb thrown by Nedeljko Cabrinovitch missed the second car, its target, and only managed to damage the third. The visitors proceeded to the Town Hall as planned, but it was decided that the museum would be left out and the Imperial party would be rushed home, going back the way they came. Unfortunately the driver, Leopold Lojka, was not adequately briefed and when they drew level with the Latin Bridge he turned right into Franz Josef Street. This gave Gavrilo Princip, waiting in Moritz Schillers caf at the crossroads, the chance he needed. As Lojka stopped and began to reverse the car on to Appel Quay, Princip stepped up to the car and fired two shots from his Browning automatic. The Archduke and his wife were fatally wounded.

The Balkans had already been the scene of war. The Ottoman or Turkish Empire had lost lands north of Greece that became Albania and southern Serbia in the First Balkan War of 1912-1913 and the attempt at settlement in the wake of that conflict led to renewed war in 1913. Although the Serbs gained territory, they still wanted a port on the Adriatic Sea, an ambition supported by Russia. The fears of the European nations had led to the formation of the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy and this was countered by the Triple Entente of Britain, France and Russia. The perception of the Entente surrounding the Alliance did nothing to calm the Germans and in particular Kaiser Wilhelm II, Queen Victorias grandson, who entertained ambitions of rivalling the British Empire. Thus, when the Austro-Hungarians had their worries about Serbian expansionism confirmed by the assassination on 5 July the Germans readily sent assurances of their support.

The decision to press matters to the point at which a European war might result was not examined in so simple a fashion. It was clear that if the Serbs were threatened, the Russians would support them. If the Russians were threatened, the French and perhaps the British would become involved. What the Italians might do was less clear. At the same time consideration had to be given to how fast events might unfold. It took time to mobilize an army and the Germans were sure they could move more quickly than the Russians, so if there was to be a war and if that meant fighting both France and Russia, being quick off the mark offered the chance of beating the former before the latter was even ready to fight. On the other hand, once set in motion the mobilization process, accelerated because of the use of the highly developed railway networks, could be difficult to halt. It was necessary to keep ones balance between starting soon enough and setting a machine in motion that could not be stopped. It was a challenge to which the potential combatants were to prove unequal.