This edition published in 2011 by Arcturus Publishing Limited

26/27 Bickels Yard, 151153 Bermondsey Street,

London SE1 3HA

Copyright 2011 Arcturus Publishing Limited

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person or persons who do any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to

criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN: 978-1-84858-429-7

AD000330EN

Edited by Paul Whittle

Cover and book design by Alex Ingr

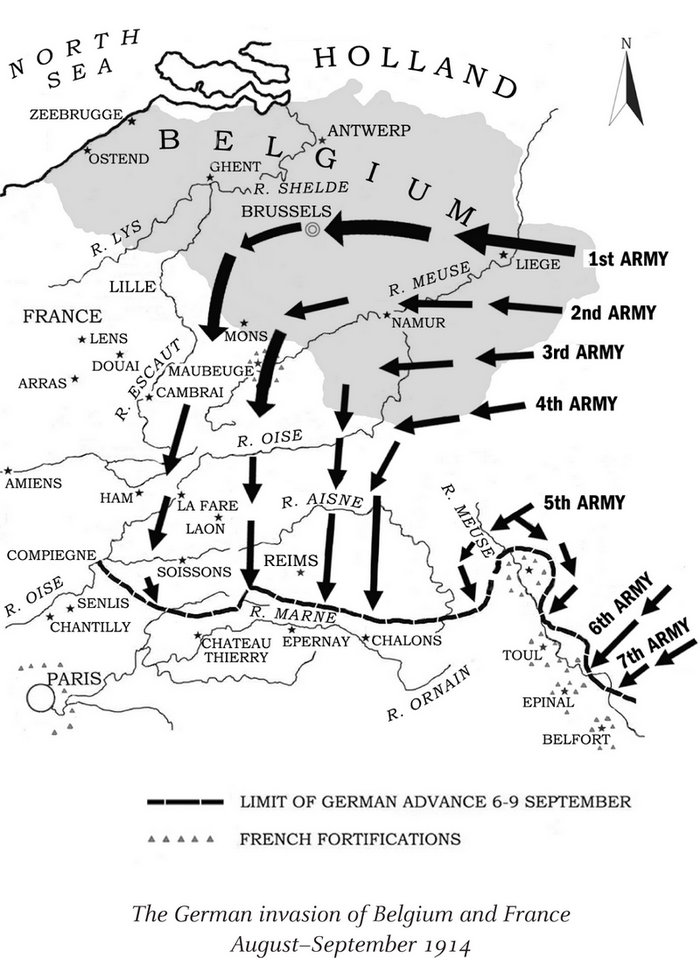

Maps by Alex Ingr and Simon Towey

Cover images Robert Hunt Library

Quotations have been given as written in the source in which they were found without the insertion of the word sic except in one instance, where it is used to emphasize the writers opinion. At the time of going to press the literary executors of certain authors have not been traced and the author will be grateful for any information as to their identity and whereabouts.

CONTENTS

M Y APPROACH To this book is a search for a framework of understanding about how the First World War was fought. The political background, its causes and consequences, are outside the scope and have been discussed at length in many other books. My personal interest is influenced by my family background northern English and Scots roots on one side, Irish-American and French on the other, so, I trust, not an exclusively Anglocentric viewpoint.

The First World War was on a scale previously unknown and in a period of unprecedented innovation. During four brief years three major new weapons were introduced gas, tanks and aircraft. Machine-guns and modern, quick-firing artillery were well-established, but the new science of using the big guns flash detection and ranging and eventually sound ranging and identification increased their effectiveness a thousand-fold. Add to all this the rigid defence line of the Western Front and you have a challenge, both tactically and strategically, that defies solution. Or defied solution for nearly four years.

The view of First World War generals and officers as deeply stupid and insensitive men, dimly driving their soldiers to slaughter is still widespread; to take this view, though, is to allow oneself to be so appalled by the suffering that one loses the power of understanding. It is much more interesting, and rewarding, to try and stand in the shoes of the men of the time and consider what they were confronted by and how, in the end, they learned new strategies and new ways of coping with the immense challenges of the new warfare.

I have tried to present the circumstances of the battles in terms of terrain, human resources, weather, weapons and planning from the viewpoints of both the commanders and the front-line combatants. The intention is to give readers a framework within which they can accept or reject my views, and form their own opinions of the conduct of military operations in the First World War.

PART ONE

OPENING MOVES

AUGUST 1914

ON SUNDAY, 28 June 1914, a temporary chauffeur got lost in a strange town. Count Franz Harrach had helped the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when he needed a car for a visit to the province of Bosnia-Herzegovina, between the Adriatic Sea and the independent, land-locked country of Serbia. The visit was not a success. On arrival the Archduke and his wife were attacked by a bomb-throwing member of the Black Hand, a Serbian nationalist secret society, as their procession drove along Appel Quay, the embankment of the River Miljacka in Sarajevo. The bomb thrown by Nedeljko Cabrinovitch missed the second car, its target, and only managed to damage the third. The visitors proceeded to the Town Hall as planned, but it was decided that the museum would be left out and the Imperial party would be rushed home, going back the way they came. Unfortunately the driver, Leopold Lojka, was not adequately briefed and when they drew level with the Latin Bridge he turned right into Franz Josef Street. This gave Gavrilo Princip, waiting in Moritz Schillers caf at the crossroads, the chance he needed. As Lojka stopped and began to reverse the car on to Appel Quay, Princip stepped up to the car and fired two shots from his Browning automatic. The Archduke and his wife were fatally wounded.

The Balkans had already been the scene of war. The Ottoman or Turkish Empire had lost lands north of Greece that became Albania and southern Serbia in the First Balkan War of 1912-1913 and the attempt at settlement in the wake of that conflict led to renewed war in 1913. Although the Serbs gained territory, they still wanted a port on the Adriatic Sea, an ambition supported by Russia. The fears of the European nations had led to the formation of the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy and this was countered by the Triple Entente of Britain, France and Russia. The perception of the Entente surrounding the Alliance did nothing to calm the Germans and in particular Kaiser Wilhelm II, Queen Victorias grandson, who entertained ambitions of rivalling the British Empire. Thus, when the Austro-Hungarians had their worries about Serbian expansionism confirmed by the assassination on 5 July the Germans readily sent assurances of their support.

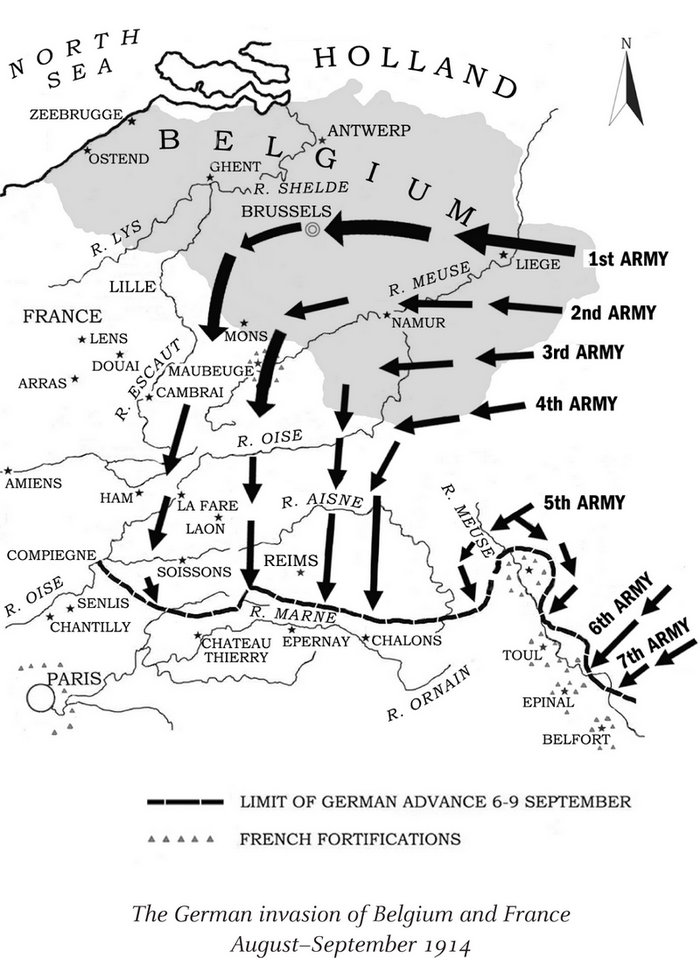

The decision to press matters to the point at which a European war might result was not examined in so simple a fashion. It was clear that if the Serbs were threatened, the Russians would support them. If the Russians were threatened, the French and perhaps the British would become involved. What the Italians might do was less clear. At the same time consideration had to be given to how fast events might unfold. It took time to mobilize an army and the Germans were sure they could move more quickly than the Russians, so if there was to be a war and if that meant fighting both France and Russia, being quick off the mark offered the chance of beating the former before the latter was even ready to fight. On the other hand, once set in motion the mobilization process, accelerated because of the use of the highly developed railway networks, could be difficult to halt. It was necessary to keep ones balance between starting soon enough and setting a machine in motion that could not be stopped. It was a challenge to which the potential combatants were to prove unequal.

Having given Austria-Hungary a loose and unconditional assurance of support, the Germans left them to it. The Kaiser went on a cruise and his ministers concerned themselves with other things. In Vienna hesitation set in. The French Prime Minister, Ren Viviani, and President, Raymond Poincar, were making a state visit to Russia from 20 to 23 July and the last thing the Austro-Hungarians wanted to do was to give two members of the Entente the chance of conferring together and issuing a joint reaction to any threat directed at Serbia. In addition, Serbias responsibility for the events in Sarajevo might be assumed by many, but needed to be demonstrated. In fact it never was. In spite of that an ultimatum was drafted in terms that Serbia could not possibly accept. It was sent on the evening of 23 July and demanded that the Serbs put a stop to anti-Austrian propaganda, proscribe the

Next page