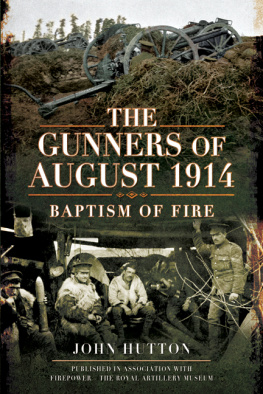

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John Hutton 2014

ISBN 978 1 47382 372 3

eISBN 9781473841130

The right of John Hutton to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd,

Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family

History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select,

Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper,

Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Preface

I n the minds of most people the First World War will always be synonymous with trench warfare and the mass slaughter inflicted by machine guns on the helpless but gallant infantry as they bravely struggled to break through apparently impregnable defences. There is good reason for the prevalence of this view of the war it is largely true. Nothing in the history of warfare before or since this titanic conflict has ever compared with the ghastly ordeal and misery of a soldiers life in the trenches. And the German machine guns did indeed take a terrible toll of British lives. It is not entirely surprising therefore that the infantrys experiences over these four long years should continue to both fascinate and appal people today. It is no surprise either that most of the contemporary history of the war should be devoted to exploring and describing this terrible reality.

What often gets insufficient attention, in my view, is the role and contribution the artillery made to the prosecution of the war effort. It is not uncommon to read histories of the great battles of the war and see the role of the artillery sometimes reduced to a few introductory paragraphs describing a preliminary barrage. The actions of the infantry normally dominate the rest of the narrative. I have long felt that this has created a distorted impression of the reality of the First World War. No one can dispute the bravery and extraordinary heroism of the infantry in this protracted and violent struggle, and nor should their sacrifice ever be downplayed. That is not the intention of this book. If we are truly to understand the nature of the conflict then what needs to be struck is a better balance. The contribution of the artillery should be equally recognised.

The fundamental truth about the First World War is that the infantry and the gunners fought together one could not succeed without the help and support of the other. This was true from the first shots of the war to the last. I hope this balance can be achieved therefore by telling the story of the war as the gunners themselves saw it. And they had a unique vantage point. The gunners may not have always shared the trench experiences of the infantry, but they were frequently the principal target of the enemys guns, and the gun line was always a valuable prize and an objective for the attackers. So although the artillerymen may not themselves have always been physically present in the front line alongside the infantry (although for much of the early fighting they certainly were), they were always in the thick of the action. Success or failure, either in offence or defence, would very often depend on the performance and responsiveness of the guns.

I have chosen to focus this book on the first few months of the First World War. These iconic months of warfare would prove to be fundamental to the whole conduct of the campaign. To the surprise of many, and contrary to much strategic pre-war analysis, trench warfare, rather than a war of manoeuvre, soon emerged as the principal feature of the fighting. But the predominance of artillery as the primary weapon on the battlefield and the effect of concentrated fire in particular would also become equally fixed points of reference around which all offensive and defensive operations would be based. Firepower would prevail over manoeuvrability and it was the guns that would provide it. In these first few months of the war vital lessons about how to best use this firepower were quickly learned lessons about equipment, tactics and strategy. These were the lessons that would lie at the heart of the eventual Allied victory four bitter years later.

Battles, of course, can only ever be successfully prosecuted if the material needs of the fighting men are satisfied. This is an often-ignored aspect of contemporary First World War history. The logistical effort involved in assembling, supplying and deploying the artillery, often in the most difficult conditions imaginable, also stands out as one of the most formidable achievements of British arms during the war. It was an effort that involved the gunners themselves, the infantry and the Army Service Corps, as well as industry back home, in a remarkable and resilient supply chain without which ultimate victory would have been for ever beyond reach. This aspect of the war serves as a poignant reminder of the hard physical labour involved in conducting military operations on the Western Front. No one knew this better than the gunners themselves. Victory would be a joint triumph of labour as well as arms.

Wherever possible, I have tried to incorporate the personal testimonies of those who served with and supported the guns. In August 1914 this was a mix of regular soldiers, men from the reserves and some Territorials. Their accounts of the fighting provide a vital and fascinating insight into the colossal tragedy and drama of the First World War.

Here, in my view, lies the real story of the war. First and foremost, it was an artillery war. Driven by the enormous capacity of industry and science, the armies of all the belligerent states developed ever more powerful guns of increasing calibre, sophistication and range. It was these weapons that inflicted more damage, and killed and maimed more soldiers than any other used in the period 1914-1918. It was ultimately British guns that swept the Allies to victory in 1918 and exerted total dominance over the battlefield not, contrary to popular mythology, the tanks, which, although a terrifying new weapon in their own right, were technically extremely unreliable and slow moving and thus highly vulnerable to anti-tank fire. It was not the advent of tanks that brought the war to its successful conclusion but the power and might of the artillery.

The history of the gunners in the First World War is, in my view, an inspiring tale of endeavour and achievement. By the end of the war the British in France had almost half a million men and nearly 6,500 guns serving with the Royal Regiment of Artillery a mighty force. It was a far cry from the heroic but tiny contingent of gunners who deployed to France in August 1914. Each of the four infantry divisions of the original British Expeditionary Force in 1914 had a complement of 76 guns and about 4,000 gunners of the Royal Field Artillery. The cavalry went to France with only 30 guns and just over 1,500 men of the Royal Horse Artillery. Their guns were mainly light field guns designed to fire relatively small calibre shrapnel shells over open sights on a flat trajectory from uncovered positions a strategy with which Napoleon and Wellington a century earlier would have been extremely familiar. Most of the guns at the beginning of the war were only equipped to fire shrapnel, which meant they were used largely as long-range shotguns. Only the howitzers (which were few in number) were provided with high explosive shells.

Next page