Bill the Bastards minder on the 15,000 tonne leviathan in the Australian flotilla was writer, poet and journalist A B Banjo Paterson. He had become the disgruntled figure of his own ballad, Clancy of the Overflow.

I am sitting in my dingy little office, where a stingy

Ray of sunlight struggles feebly down between the houses tall,

And the foetid air and gritty of the dusty, dirty city

Through the open window floating, spreads its foulness over all.

And the hurrying people daunt me, and their pallid faces haunt me

As they shoulder one another in their rush and nervous haste,

With their eager eyes and greedy, and their stunted forms and weedy,

For townsfolk have no time to grow, they have no time to waste.

Patersons narrator dreamt of going bush and living under the stars like his old mate Clancy. But the poet himself was fifty years of age and bored with what he considered to be a struggling humdrum existence. His ballads had brought him fame, and it extended to the UK, where his works conjured outback imagery for the British who had hitherto considered Australia as just a former prison colony. The intensely urbane and intelligent Paterson, with his penchant for bow-ties and bon mots, had created a romantic dimension to life in the Antipodes. He had made his name as a war correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald during the Boer War and even more so as a writer who captured in words the rhythms of the bush and an era in a nations moods, culture and environment. This was a rare achievement for an author anywhere, at any time.

He was a lawyer by profession, with a patricians mien, yet he was a poet with a common touch who could deliver simple, compelling bush and city imagery understood by all who read him. The law bored him as much as accountancy did the clerk of his ballad, who faced the round eternal of the cash book and the journal. After his South African experience he gave away his law practice, vowing never to take up a deskbound role again. Instead he toured the country lecturing about the Boer War. This kept Patersons interest up, yet it petered out by 1903 when he was approaching forty. His good connections from his schooldays at Sydney Grammar helped him gain the editorship of Sydney Evening News. Paterson once more had a desk, but there was something altogether more stimulating for him in this job, even if he were unsuited to the pace and demands of daily journalism. It allowed little time for reflection, and by nature Paterson liked to go deeply into his minds crevasses. He stayed in the job for a time before taking on the editorship of the more leisurely Town & Country Journal.

After that, he travelled abroad to Europe. His nostrils filled with the whiff of coming war. But Patersons health failed and he returned home to take up farming. This generated more time for reflection and avoided the Clancy syndrome of city life, but the poet and adventurer remained restless. He married at forty, and this for a time took his mind off the self-indulgent need for permanent stimulation in his professional life. His choice was the attractive and genteel 25-year-old Alice Walker, but the normal restrictions of marriage did not suit him.

Patersons main frustration was that his true lovewriting poetrypaid too little to provide for himself and a family. He spoke of the battle to keep ahead of the bills. Even his wonderful Clancy, The Man from Snowy River and the classic Waltzing Matilda brought him a pittance in royalties. This created a sense of cynicism about being so talented yet going unrewarded for it. Artist Norman Lindsay, who worked for The Bulletin as a cartoonist and illustrator, shared something of the same feelings. He described Paterson as sardonic after his decades in journalism, and because of the poor returns for his genius as an original Australian poet.

When war broke out in Europe in August 1914, Paterson had a sudden vision of escape from his permanent state of ennui. He would become a war correspondent once more. He had done it so well before and, besides, the military was part of his heritage, if not his DNA. His great-grandfather, Major Edward Darvall, served under Wellington, first in India and then defending the English coast from Napoleons threatened invasion. A great-uncle became a major-general in the British Indian Army. (There was a political heritage too. Another great-uncle became attorney-general of New South Wales and a leader of the Sydney establishment.)

Paterson would again be both revived and excited by battle, travel and competing for a scoop. He anticipated seeing London and Paris a second time. This was what he wanted. The thought thrilled him. He rushed to the Herald to make a case for it hiring him as a war correspondent, but he was turned down. The federal government, under subtle instruction from the seat of Empire in London, would pick and choose whom it wanted in its propaganda arm, which is how it saw the press. The Herald had already chosen Charles Bean to be its reporter. Bean would also act as the official war historian. So much for independent reporting. He had just pipped Keith Murdoch of the Melbourne Herald for the job. The earnest, pedestrian Bean was a good choice. Murdoch was more interested in power than the tedious recording and collating of every event Australia was to take part in on several war fronts. Murdoch instead became the representative of two successive wartime prime ministers, Andrew Fisher and Billy Hughes, when they were not visiting the UK. In effect, he was Australias official voice in Londons halls of power. These quasi-governmental roles were never right for Paterson and he knew it. He wanted utter freedom of expression or nothing. In the end he was left with the latter.

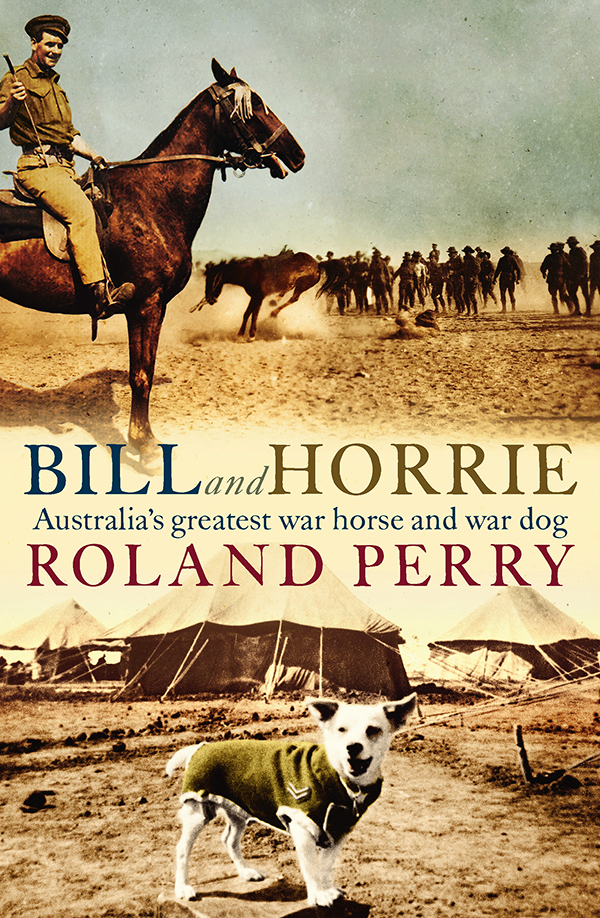

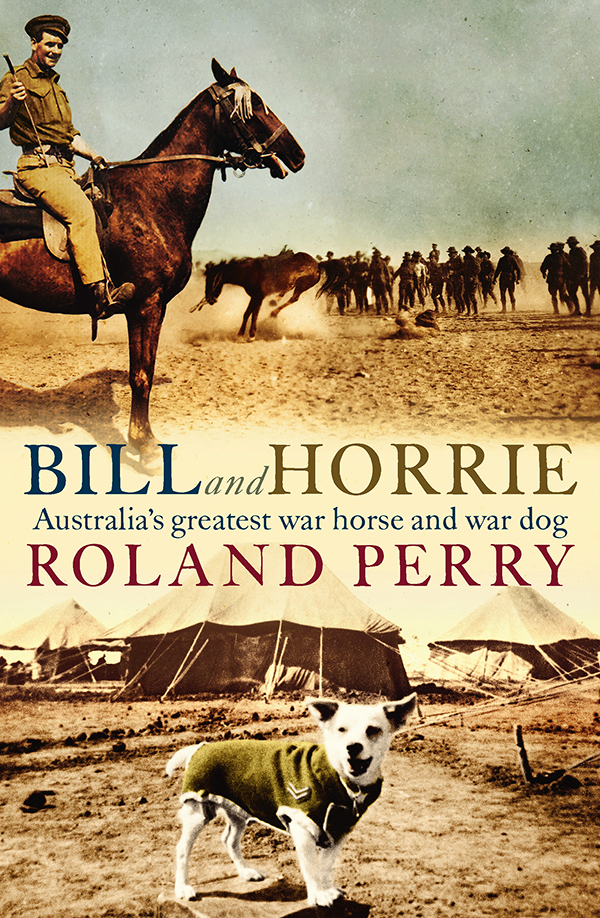

In desperation he turned to his second true love (wife Alice aside), which was horses. He had been brought up in the bush where these treasured and essential animals were a big part of his early life. Paterson could ride almost as soon as he could walk. He was a fair horseman despite an arm deformity caused by an accident when he was young. Horses would help facilitate his travel to war via the barn door. He secured a tenuous role as an honorary veterinarian on a troop ship carrying horses and soldiers. It was a touch humiliating to go to such lengths to escape his conventional life, but Paterson was good on spin. He would write and despatch from wherever the horses went. He would gain insider knowledge and connections. One was the diminutive, well-bred 49-year-old Harry Chauvel, the lean-as-a-ferret, rigid-backed commander of Australias first ever Light Horse Brigade, which would form part of the nations 2nd Division. They were nearly the same age, and their paths had crossed briefly at Sydney Grammar.

Patersons life was re-energised. He went about his new job with the enthusiasm of a keen first-year cadet journalist, writing his first piece as a freelance for theHerald called Making an Army.

Before Banjo Paterson could revive his career as a war correspondent he had a duty in his role as a would-be vet on board ship in charge of his own horse and a score of others, including Bill the Bastard. Paterson was travelling with 27 qualified vets in the main medical ship. In all there were more than 8000 horses in the 38 transport ships and their minders were kept busy with inevitable equine sickness. Paterson loved his own mount, a sleek, smaller Waler he called Trumper after the cricketer Victor Trumper. But as they steamed into the Indian Ocean he grew fonder of Bill than of any other animal.

Everyone knew the temperamental Bastards reputation and Paterson was cautious with him. Yet he found an unusual connection. Paterson reckoned this exceptional animal tackled his world in the same way he did his. Bill bowed to no human or thing. Paterson hated bosses or being told what to do. A mutual respect developed. Paterson found himself talking to Bill with more care than he did with any of the other horses. The Bastard in turn didnt kick, but for a couple of occasions, when he was too near. He didnt try to bite him or nudge him out of the way, which he was wont to do with any other vet who came close. The army vets were wary but Bill didnt need anything from them, apart from food and water. When other horses near him had colic, stress or, in a few cases, pneumonia, he remained well.

Next page