Unless otherwise stated all colour photographs of the Roman Baths are Bath & North East Somerset Council. Photographer, Jonathan Reeve.

This electronic edition published 2013

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberleybooks.com

Copyright Patricia Southern, 2012, 2013

The right of Patricia Southern to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-4456-1090-0 (PRINT)

ISBN 978-1-4456-1590-5 (e-BOOK)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

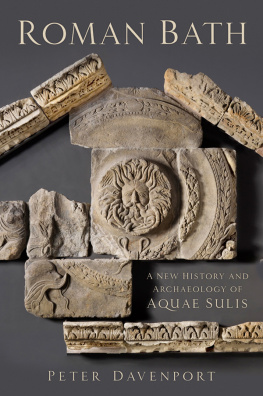

It is probably safe to say that Aquae Sulis was unique in Roman Britain, because it did not slot conveniently into any of the categories of Romano-British civil settlements, and no other site could boast such an impressive array of spa baths, conventional baths, temple precinct and healing springs. Similarly, modern Bath, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is unique among the many Roman remains that have been explored in Britain. No other Roman classical temple in Britain is so well known as the temple of Sulis Minerva, where enough sections have been found of the temple pediment and of the columns that supported it to be able to reconstruct its appearance and size. The temple of Claudius in Colchester was probably more important and much more elaborate, but the Normans used whatever was left of it in the eleventh century as the foundation for their huge castle, ensuring that nothing much remained of it for archaeologists to explore. Fortunately for Bath, the Normans did not build a castle on top of the Roman temple. By the time of the conquest by William I, not much of Roman Bath was known, because the hot springs bubbling up more or less undisturbed for the past five or six centuries had buried the Roman town under a thick layer of mud. When the Kings Bath was built around AD 1100 and named after Henry I, there was no sign whatsoever that the baths were being erected on top of the sacred spring with its enclosing superstructure, and no-one suspected that the temple of Sulis Minerva lay nearby. During the medieval era it was known that Bath had been a Roman settlement, because many inscribed stones had been used in its walls, but it was not until the eighteenth century when new buildings were being erected that more and stronger evidence was found to show that there had been a temple in the town dedicated to Sulis Minerva, who is attested on several inscriptions.

Anyone trying to write about Roman Bath has to acknowledge and admire the work of Professor Barry Cunliffe and the Bath Excavation Committee formed in the 1960s and then superseded by the Bath Archaeological Trust. The City Council and the Museums Service have always entertained an enlightened attitude to the archaeological investigations and the presentation of the remains and the finds, updating the displays and the guidebooks when such revisions are deemed necessary by further discoveries. There is still much to be learned about Roman Bath, so hopefully new books will always be appearing, which provides a good enough excuse for this one. As well as summarising the archaeology that is exhaustively covered by Professor Cunliffes books, I have tried to include information about Roman Britain in general so it can be seen how the town fitted into the context of events and trends of the province of Britannia, and sometimes in the Empire, at various stages in the history of Aquae Sulis.

Patricia Southern

Northumberland

2012

1

BATH BEFORE THE ROMANS

The water that bubbles up through the three hot springs of Bath is very old. This is not just because the site was known to the prehistoric people of the area and then developed much later by the Romans, but because it can take several thousand years for the rain that falls on the Mendips to sink down through the rock towards the centre of the earth, re-emerging with its acquired heat and minerals to provide the spa town with its famous baths.

On the way down through the earths crust the rainwater approaches but does not reach the hot molten core, absorbing more and more heat as it descends. At a depth of about 3,000 to 4,000 metres, at a temperature somewhere between 60 degrees centigrade and 90 degrees centigrade the water reverses its course and starts to come back to the surface, losing some of its heat but none of its minerals and salts as it gushes from the earth at the rate of 250,000 gallons a day. The hot spring water emerges at one point of origin deep within the earth, but before it finds its way out at ground level it splits up via three different outlets, all quite close together.

The temperature of the water varies a little between the three springs. The appropriately named Hot Bath is the warmest at 49 degrees centigrade (120 degrees Fahrenheit), and the Cross Bath spring the coolest at 40 degrees centigrade (114 degrees Fahrenheit). The Kings Bath spring provides the strongest and most prolific flow of water, at a temperature of 46 degrees centigrade (117 degrees Fahrenheit). The orange colour that stains the baths derives from the iron content of the water, and besides the iron there are over forty other minerals, the most prevalent being calcium sulphate, sodium sulphate, and magnesium chloride, with lesser proportions of strontium sulphate, potassium sulphate, calcium carbonate, and sodium chloride. There are also traces of lithium, bromine and silica.

The original Roman bathing complex of the first century AD was continually enlarged and developed, covering a large area of the town. When the medieval and modern baths were built there was little if any knowledge of the Roman structures that lay beneath them, though it was clear from the remains of sculptures and inscribed stones that the Romans had occupied the place. The Kings Bath is said to have been named in the twelfth century after King Henry I, and the name was retained through the following centuries. When John Leland visited Bath in the reign of Henry VIII he described the Kings Bath, the Cross Bath and the Hot Bath, and in 1610 John Speed included a drawing of the Kings Bath in his map of Somerset, showing it just as Leland described it, enclosed within a rectangular, walled precinct, with an inner arcade all round the bath providing niches for the bathers to stand in. The Pump Room was an additional building of the eighteenth century, originally built in 1706, by Richard Nash, better known as Beau Nash. Nearly a century later the Pump Room was rebuilt in its present form by John Palmer. It was re-opened to the public in 1799. The names of the bathing establishments became more elaborate as time went on. A nineteenth-century guidebook lists the Kings Bath, the Queens Bath, the Old Royal Baths, where the Hot Springs emerged, and the New Royal Baths. These were open on weekdays from 7 a.m. till 7 p.m. The current names have reverted to the usage of medieval times: the Kings Bath, the Cross Bath and the Hot Bath. The Great Bath is the main Roman one.

The site where the Roman town of Bath was to be established is surrounded on the west, south and east sides by a loop of the River Avon, with open, hilly land to the north and north-west. The spring of the Kings Bath emerges between two small hills, while the waters of the Hot Bath and the Cross Bath rise a short distance away on the hill to the west of the Kings Bath. No-one knows what the ancient Britons called the place, but when the Romans arrived and named it Aquae Sulis, the Waters of Sulis, they presumably preserved the name of the Iron Age British deity who was associated with the springs. From the very earliest times onwards, the ancient Britons could not have failed to notice the site, where the hot water bursting from the three springs would have created a misty environment all around the surrounding marshy area, and the land and vegetation would have been stained with the orange colour left by the iron content of the water.