Praise for 1984: Indias Guilty Secret

A comprehensive and fluent account

Literary Review

Exhaustive and relentless were left wanting to continue the investigation ourselves.

Los Angeles Review of Books

This book is a timely reminder of Indias shameful inability to account for that explosion of racial and religious hatred after Mrs Gandhis assassination, when eight thousand Sikhs were butchered and burned. The failure to punish this crime against humanity remains Indias guilty secret.

Geoffrey Robertson QC

This is a powerful and compelling study of an appalling case of mass violence in the worlds largest democracy. This careful study is a vital response to those whose denial of the crime continues to wound survivors and their descendants.

Professor Philip Spencer, Emeritus Professor in Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Kingston University

Pav Singhs book makes for necessarily difficult, yet necessary, reading. He illuminates events still too little understood, not least in the UK, and painstakingly discusses their aftermath and memory.

Dr Paul Moore, Deputy Director, Stanley Burton Centre for Holocaust & Genocide Studies, University of Leicester

This work has been long overdue in coming since there is far too little writing on 1984. Now, 33 years later, Pav Singh provides a new way of looking at the targeted killings of Sikhs by placing it within the developing international jurisprudence on state-sponsored killings of specific communities and sexual violence upon its women. Other unique aspects of the book are the accounts of what happened to the victims in hospitals, police stations and trains.

Dr Uma Chakravarti, Indian historian and feminist

To the victims of Churasee (1984) and the many individuals, of all faiths and none, who offered shelter and relief, and continue to fight for justice

On the contrary, war hysteria is continuous and universal in all countries, and such acts as raping, looting, the slaughter of children, the reduction of whole populations to slavery are looked upon as normal, and, when they are committed by ones own side and not by the enemy, meticulous.

The past is what the records and the memories agree upon. And since the party is in full control of all records, and in equally full control of the minds of its members, it follows that the past is whatever the party chooses to make it.

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

Contents

Sikh houses and shopswere marked for destruction in much the same way as those of Jews in Tsarist Russia or Nazi Germany for the first time I understood what words like pogrom, holocaust and genocide really meant.

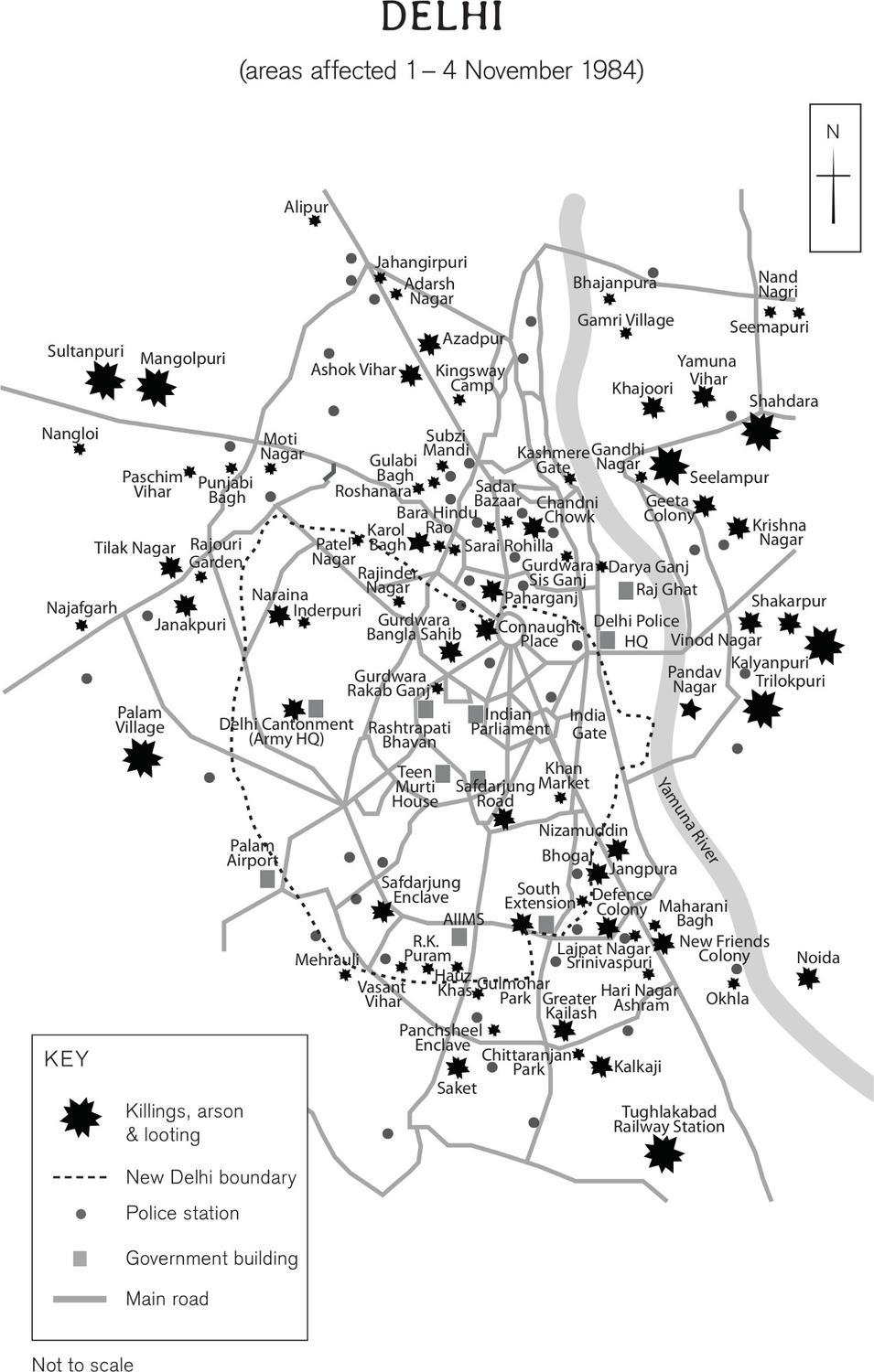

One of Indias best-loved authors and journalists, the late Khushwant Singh, wrote these harrowing lines about the India of November 1984. He was describing his own experiences of being caught up in the wave of genocidal killings that swept through the capital, Delhi, and further afield following the assassination of the prime minister, Indira Gandhi, by two of her Sikh bodyguards.

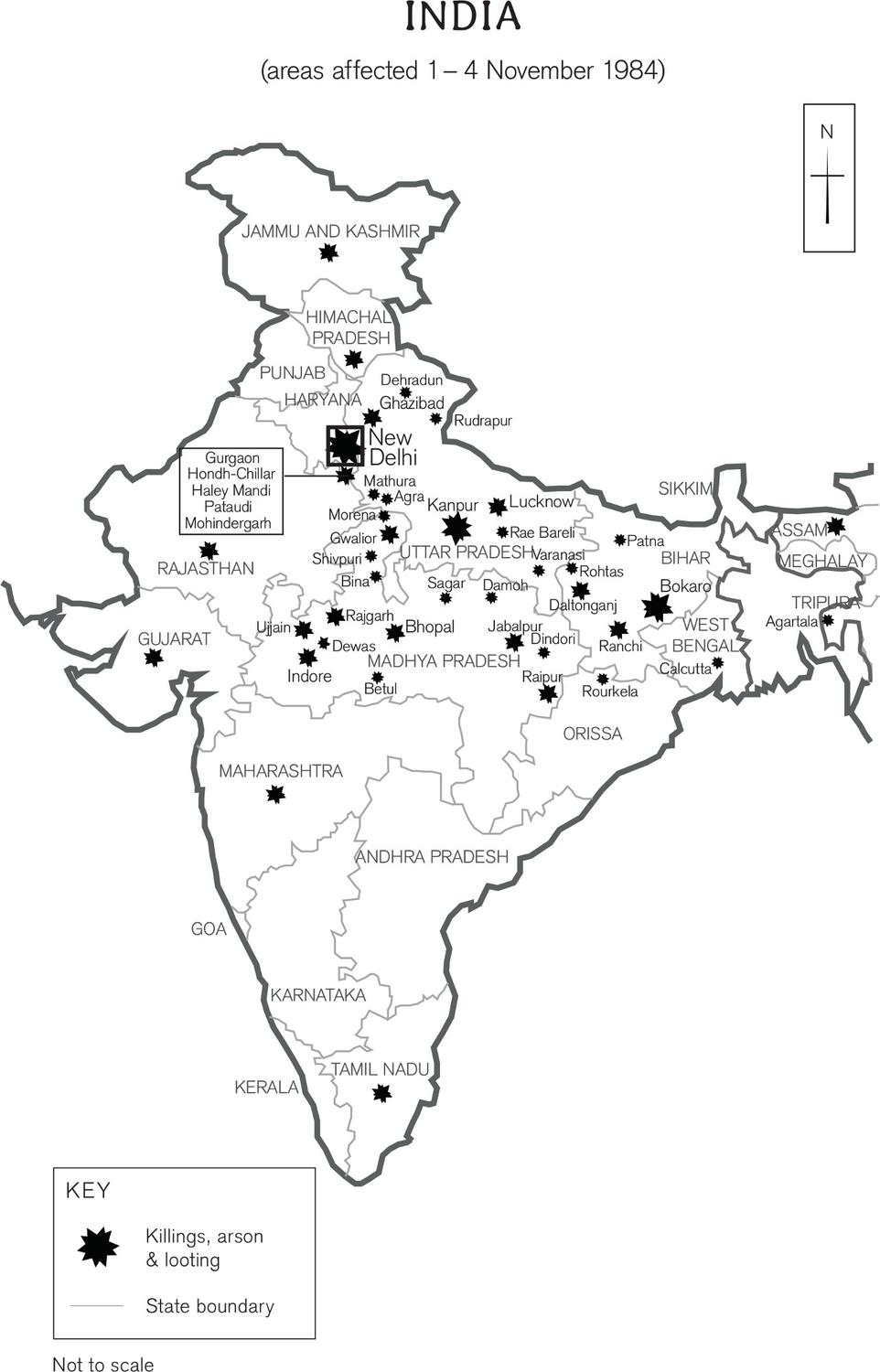

Over four days, an estimated 8,000 Sikhs, possibly more, would be slaughtered by rampaging mobs in the worlds largest democracy. To put the sheer scale of this destruction into perspective, the figure cited is broadly equivalent to the civilian death tolls of the Northern Ireland conflict, Tiananmen Square and 9/11 combined. The eminent British lawyer and campaigner Geoffrey Robertson QC rightly calls it Indias guilty secret a phrase that so succinctly sums up the crimes that it lends itself to the title of this book.

At the time, the authorities projected the violence as a spontaneous reaction to the tragic loss of a much-loved prime minister. But evidence points to a government-orchestrated genocidal massacre unleashed by politicians with the trail leading to the very heart of the dynastic Gandhi family and covered up with the help of the police, judiciary and sections of the media.

The Indian government of the day worked hard on its version of events. Words such as riot became the newspeak of an Orwellian cover-up, of a real 1984. To protect perpetrators, the most heinous crimes have been obscured from view: evidence destroyed, language distorted and alternative facts introduced. The final body count is anyones guess. As the celebrated author and essayist Amitav Ghosh, another witness to the scenes in Delhi in 1984, has stated: Nowhere else in the world did the year 1984 fulfil its apocalyptic portents as it did in India.

And yet what may well go down in history as one of the largest conspiracies of modern times is hardly known of outside of India. At the time, Western governments toed the line of their Indian counterparts and downplayed events arguably for fear of losing trade contracts worth billions to the misnomer of communal riots.

Global reaction to other atrocities such the killings in Chile by the Pinochet regime, Chinas Tiananmen Square massacre and the large-scale, post-World War Two genocides of Cambodia, Rwanda, Darfur and Syria has rightly been firm and unequivocal. Each received considerable global attention and international condemnation from governments, human rights organisations and high-profile campaigners.

By way of comparison consider how the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia recognised the Srebrenica massacre of 1995, in which 8,000 Bosnian Muslims were slaughtered, as a genocide. But for the innocents of November 1984, there has been a deafening silence, a lack of comparable international concern or consideration of the nature of the violence which has allowed the guilty to evade justice and crimes to go unrecognised for what they actually were.

~

As the events of November 1984 were unfolding, I was a teenager living at home in Leeds, England. My familys initial shock on hearing that Mrs Gandhi had been killed turned to anxiety and concern for relatives in Delhi, for others in the capital and for how India would react. A maternal aunt, Sukhdev Kaur, lived with her family in Janakpuri, an area in West Delhi that had fallen prey to the organised violence. We rang countless times a day, our worry increasing every time the phone remained unanswered.

A full week later our fear turned to relief when my mother spotted my uncle, Tara Singh Brar, whilst watching a BBC TV news report my uncle, aunt and their four children had managed to escape to the safety of one of the many refugee camps that had sprung up across Delhi to house thousands of displaced and victimised Sikhs.

Years later I would learn how, in order to survive the ordeal, the family had taken shelter with their Hindu neighbours who themselves had risked everything by harbouring them. In their neighbourhood the Sikh-owned Janak Cinema and gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship) had been attacked by the mobs, which were becoming an ever closer danger. To survive, they had had to resort to extreme measures the men removed their turbans and cut their long hair, symbols of their faith. My oldest cousin, Ishar Singh, managed to smuggle his father from Janakpuri to the safety of the camp on his motorbike, revolver in hand.

~

By the late 1980s I became politically active as an undergraduate studying in London. I was involved in various human rights and social justice causes, joining the Anti-Nazi League and campaigning against apartheid rule in South Africa. It was on this latter issue that Rajiv Gandhi, Indira Gandhis son and successor as the prime minister of India, rose to global prominence, emerging as a crusader against the regime and a proponent of sanctions. Here was the face of modern India liberal, dynamic and a serious actor on the world stage. But every time I saw him on TV or read his name in the papers, my stomach churned at the thought of the outrageous contradiction between his words on apartheid and his alleged role in the sickening crimes that were perpetrated against his fellow countrymen under his watch.