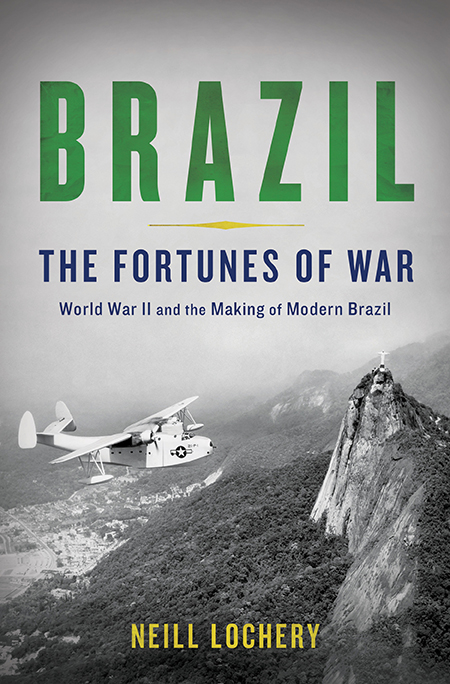

Brazil

The Fortunes of War

World War II and the Making of Modern Brazil

Neill Lochery

a member of the perseus books group new york

For Emma, Benjamin, and Hlna

Contents

Introduction

N estled in the foothills of the Serra do Mar mountains and fronted by the brilliant strip of Copacabana Beach and the glassy expanse of Guanabara Bay sits Rio de Janeiro, known to its inhabitants as Cidade Maravilhosa, or Marvelous City. Founded in the sixteenth century in a dimple in Brazils southeastern Atlantic coastline, Rio de Janeiro today has more than earned its nickname. The citys waterfront districts bristle with skyscrapers, museums, monasteries, and luxury apartment buildings interlaced with parks, shopping centers, and pedestrian malls. Rios famed Carnaval annually draws millions of Brazilians and tourists to comingle in the citys streets. During the rest of the year, tourists and locals dance to the rhythms of samba in Rios ample array of bars and nightclubs, soak up the sun on its magnificent beaches, inspect its colonial architecture, or rotate through its historic neighborhoods on its many subway, bus, and rail lines.

In Rio, the vibrant economic energy that has come to characterize Brazil thrums loudest. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, Rio is the second largest city in Brazil, and the sixth largest in the Americas. And while Rios domestic political importance may no longer match its economic might, for much of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries Rio was the federal capital of Brazil and thus the locus of Brazilian power, fully defined: first during the countrys colonial period, then during its brief elevation as a kingdom within Portugals transcontinental monarchy, and finally in the first one hundred and forty-odd years of Brazils existence as an independent state.

By the time Brasliathe newly minted federal capitalsupplanted Rio in 1960, the Marvelous City had left an indelible mark on the rest of the country. In the decades before that switch, the federal leaders who reigned from Rio presided over Brazils transition from a lush but neglected tropical backwater to one of the most dynamic nations in South America, and indeed in the entire world. Brazil today ranks among the top ten countries in the world by gross domestic product (GDP), and with its growth rate remaining reliably high, the nation is poised to rise even further in the decades ahead. The story of how this economic miracle occurred, however, has never been fully told.

At the outbreak of World War II, Brazil was a completely different place than it is today. In 1938, the year before the war began, Brazil was the fourth largest nation on the planet and covered nearly half of the total area of South America. At 3,275,510 square miles it was larger than the continental United States, but its population at the start of the 1940s was roughly forty-three million peopleabout a third of the US population at the time, and less than a quarter of Brazils current size of two hundred million. The country was largely divided between its developed areas, which included the cities of Rio de Janeiro and So Paulo, and the hugely underdeveloped interior of the country. Good-quality infrastructure was almost totally absent, with substandard road and rail links between even the most populated parts of the country.

Links to the outside world were equally inadequate. Air service to the United States took days, and connections to Europe were not fully developed. Rio de Janeiro was a frequent port of call for ocean liners, but only very rich Brazilians could afford to travel abroad. Most Brazilians only read about cities such as London, Paris, and New York in the local newspapers; they never saw them. Partly as a result of its geographic isolation and also due to its language (Brazil was the only Portuguese-speaking country in South America), Brazil remained largely cut off from the outside world.

During the course of World War II, this was all to change. Thanks in large part to an alliance with the United States, in the 1940s Brazils industry, transportation infrastructure, and political position in South America and the world underwent a radical transformation. The war led to the birth of modern Brazil and its emergence as one of the economic powerhouses of the world. And Rio de Janeiro was, and indeed still is, the linchpin of the Brazilian dynamo.

Astute observers may have detected in prewar Rio something of the restless energy that would give the city such a pathbreaking role in Brazils future. Prior to the outbreak of World War II, Rio de Janeiro was a beautiful, exotic, and slightly chaotic off-the-beaten-track location for wealthy locals and superrich international playboys seeking fun and adventure. The lack of top-quality port facilities and a decent international airport made it more difficult for international businessmen and all but the hardiest tourists to reach Rio. Once they arrived, however, these intrepid men and women found themselves in a city that clearly aspired to a level of cosmopolitanism all but unknown in South America.

Rio in the late 1930s was a hub for sophisticates, powerbrokers, and intellectuals who, whether by birth, choice, or necessity, found themselves in the southern hemisphere of the Americas. Central to the citys vibrant social scene were the five-star Copacabana Palace Hotel, located in front of Rios most famous beach, and the Jockey Club, built on land reclaimed from the citys large lagoon. The Copacabana Palace, which opened in 1923, was one of the best examples of art deco buildings in the city, and was the place to been seen for international revelers and members of Rios high society. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers danced in its magnificent ballroom. The Jewish writer Stefan Zweig, who fled Nazi persecution in Europe, stayed at the hotel before he and his wife committed suicide in 1942 in the city of Petrpolis, some forty-five miles from central Rio. During World War II the likes of Clark Gable, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and Walt Disney were in residence in the Copacabana Palace Hotel, all on special wartime missions for the American government.

Across the city, the Jockey Club was where the elite of Brazilian society met and did business during the long horse racing season. The racing took place on balmy evenings from spring through autumn as the sunset cast its shadows over the skyscrapers in the city. Chairs next to the racetrack were arranged in strict social order, with society ladiesdecked out in fur coats and designer dresses from the top fashion houses in Europetaking their place in the front row. Male members of the Jockey Club were carefully turned out with slicked-back hair and wore loosely cut white linen and cotton suits, white shirts, and colorful kipper ties, all rounded off with shiny two-tone correspondent shoes.

A frequent patron of the Jockey Club was Brazils charismatic president, Getlio Dornelles Vargas. Physically, he was not a memorable man; short and portly, he had a waistline that ballooned during his later years. While sensitive to the allegations of vanity leveled at him by political opponents, Vargas did nothing to dispel them. He was known to color his hair and was always well dressed; in winter, he often wore his favorite blue-gray suit, and in summer, he was seen in white cotton suits and club striped ties. Despite his lack of physical presence, however, there was an aura around Vargas. He projected an air of calmness and contentment, and his legal backgroundVargas had been trained as a lawyer before entering politicsgave him a deliberative and circumspect quality. He was often found gently puffing on a Brazilian cigar or hosting intimate card games; poker was his personal favorite.