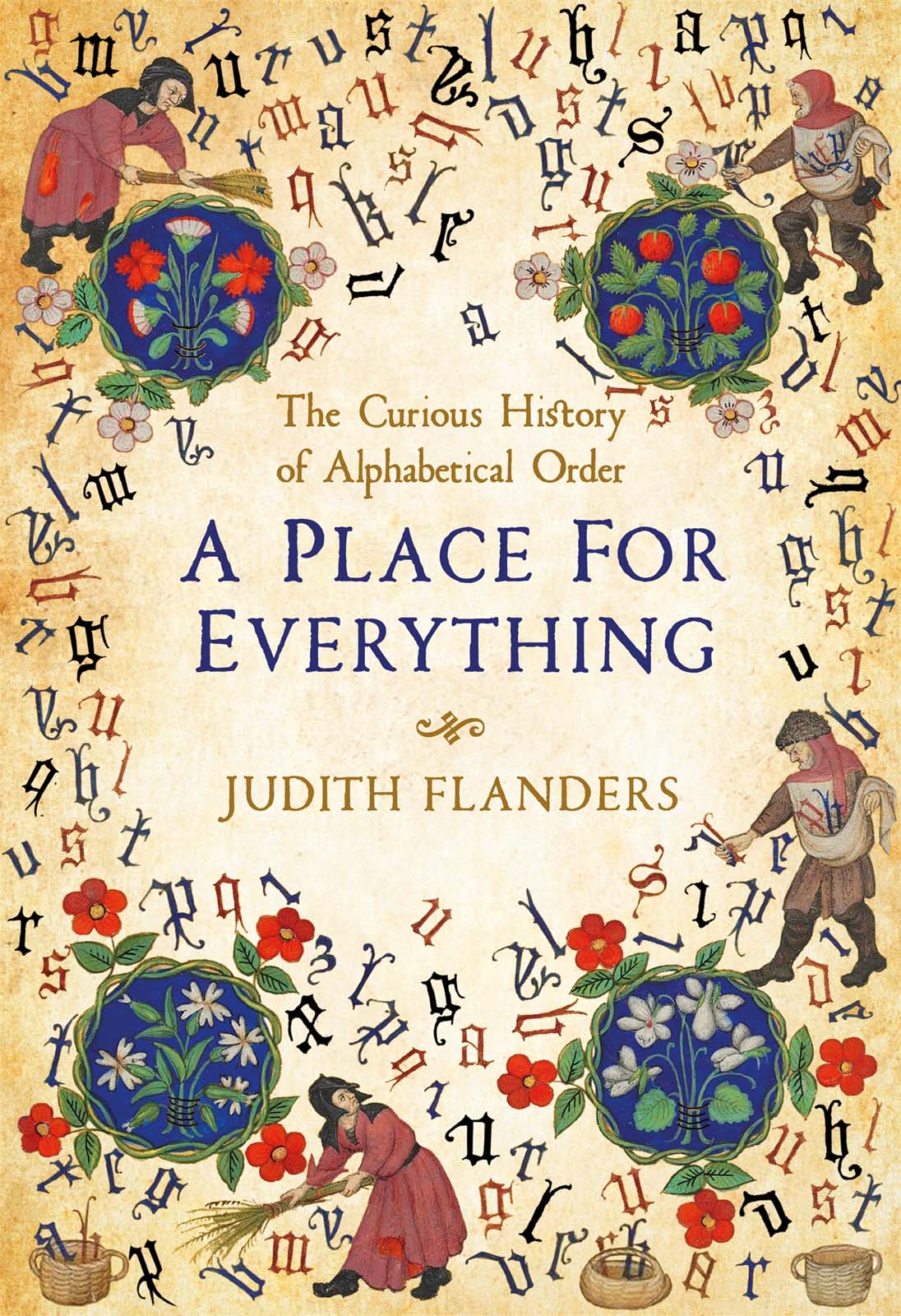

JUDITH FLANDERS

A Place for Everything

The Curious History

of Alphabetical Order

The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity... We fail to be struck by what, once seen, is most striking and most powerful.

LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN Philosophical Investigations, 129

In memory of my grandmother

Doris K. Morrison

Who loved a good tidy-up

Contents

List of Illustrations

IN THE TEXT

IN THE PLATE SECTION

Acknowledgements

As always, my debts far outweigh my ability to thank people and institutions.

I am grateful, first and foremost, to the unknown curators of the Joseph Cornell exhibition at the Royal Academy, London, in 2015, for setting me on a path to look anew at the subject of categories and classification, and to the work of Joseph Cornell himself, for making me realize how very strange the notion of classifying is.

More pragmatically, I am grateful to Dean Antonia Maioni, and to McGill University, Montreal, Canada, where I spent a summer as a Visiting Scholar, and where a great deal of the research for this book was done. My thanks go also to Dr Richard Cruess, who made the initial contact for me. Christopher Lyons, Head of Rare Books and Special Collections, together with his team, welcomed me, and I am grateful to them, particularly to Melissa Como, who more than once patiently walked me through their systems. My thanks are also due to Associate Dean Nathalie Cooke, Professor Faith Wallis and Associate Professor Trevor Ponech, for many interesting conversations and useful threads.

My debts to other institutions are no less. To the London Library and the British Library, and their extraordinarily helpful staffs. To Herr Wolfgang Mayer of the Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg, who assisted me with scans and information about that collections catalogue of the library of Jeremias Martius. To Joseph Gerdeman and the Interlibrary Loan Department of the University of Chicago, who graciously bent the rules to get me a PDF of an otherwise unobtainable pamphlet.

Simone Mollea generously took my very basic and often worse Latin, and rendered it into a polished translation. His help was invaluable, and I thank Professor Matthew Fox, too, for making the introduction. Peter Gilliver, of the Oxford English Dictionary, sustained a helpful and most enjoyable email correspondence when Im sure he had many better things to do. Shaun Whiteside and Tobias Hoheisel were endlessly patient with my queries over Dutch and German translations. I am most grateful to them all.

Justice Nicholas Kasirer, Professor Faith Wallis and Edward Tenner all supplied me with copies of their work when the stalwart efforts of the above libraries failed. Heidi Graf located an image of an early Froschauer broadside and reported on its organizational principles for me. Jean-Jacques Subrenat was enlightening on the subject of Chinese characters, pinyin and computer technology. Professor Lucy Freeman Sandler guided me to an important essay of hers that I had regrettably overlooked, and supplied me with a scan of an image. Caroline Shenton kindly responded to a late query on fonds and archival practice. Again, I owe gratitude to all.

At Picador, my thanks go to Nicholas Blake, Neil Lang, Philippa McEwan, Lindsay Nash and the inestimable Charlotte Greig, who always exerted calm control. Finally, I must thank my agent, Bill Hamilton, of A.M. Heath, and my editor, Ravi Mirchandani, of Picador Books, neither of whom laughed, or at least not to my face, when I told them I wanted to write a book on the history of alphabetical order.

Preface

Writing, from its earliest days, has been thought of as a gift from the gods: in Egypt it was given to humanity by Thoth, the god of culture; in Babylonia, by Nebo, the god of destiny; in Sumeria, it was bestowed by Nab, the scribe of the gods. The Greeks sometimes thought writing was granted to mankind by Hermes, the messenger of the gods; at other times they reported that it was given by Zeus to the Muses. Odin bestowed the gift in Norse legend; in India, the elephant-headed god Ganesh used one of his tusks as a pen; while the Mayan Itzamna, a creatorgod, first named the objects in the world, and then gave humans the ability to write those names down. The Jews were taught that God had handed the skill to the world through his intermediary, Moses; in the Quran, Allah is he who taught the pen. As late as the fifteenth century, hangul, the newly created script of Korea, was said to have been produced by the revelation of heaven to the mind of the sage king.

How writing came to be, it appears, is a question that has been explored for almost as long as writing itself. And therefore what writing does it enables us to read, to gather information and to pass that information on seems so obvious that we barely consider the magnitude of this ability. Yet reading, and writing, and what we do with those things, are not obvious at all. As we will see, the world broadly divides into two types of writing systems: alphabetic and syllabic; and ideographically based methods. The alphabet, as far as we can tell, was written from its very earliest days in a set order. Why, we dont know, although ease of memorization seems possible, even likely. Non-alphabetic writing systems, by contrast, were organized in a variety of ways by sound, by meaning, by written structure or shape.

To readers and writers of an alphabetic language such as English, the assumption I just made above that the elements that make up a writing system, the characters, must be ordered, must be sorted or organized in some way is automatic, and unquestioned. Equally, it has become automatic to assume that, once our writing systems evolved, writing was used to give permanence to thoughts and ideas; and then, that methods were devised to enable us to return to those thoughts and ideas, whether ours or someone elses. For writing is a powerful tool not merely a tool that permits Person A to notify Person B that such-and-such occurred, or will occur, or some other piece of information, but a tool that enables Person B to be notified of these occurrences centuries after Person A has died.

Writing is powerful because it transcends time, and because it creates an artificial memory, or store of knowledge, a memory that can be located physically, be it on clay tablets, on walls, on stone, on bronze, papyrus, parchment or paper. And for centuries, that is how it was used. Words were written, and stored. We can guess from what has survived that it was expected that these items would be referred back to. But how, and why, did we learn this art, or science, of reference, of looking things up? How did we learn to find what we needed when we needed it, in the mass of written words that have surrounded us daily for a millennium and more?

It is hard today to imagine not being able to look something up not to know how to use an index, a dictionary or a phone book. It is harder still to imagine a world in which there are no indexes, no dictionaries or phone books. Ordering and sorting, and then returning to the material sorted via reference tools of various kinds, have become so integral to the modern Western mindset that their significance is, at one and the same time, almost incalculable, and curiously invisible. For categorizing is what we do every day of our lives, frequently every hour of every day, and not just through paper. We use dozens of products every day without ever considering that they have been specially designed for our perpetual sorting needs, to enable us to locate material swiftly and without effort.