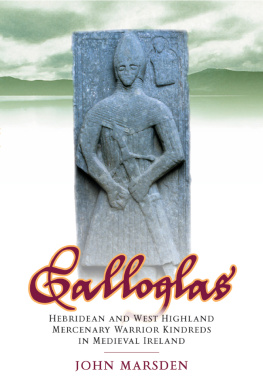

GALLOGLAS

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2011 by

John Donald, an imprint of

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright John Marsden 2003

ISBN 978 1 906566 39 5

eISBN 9781907909351

First published in 2003

The right of John Marsden to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record is available

on request from the British Library

Typeset by Hewer Text Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and Eastbourne

For my friend Keith Durham who first introduced me to the galloglas some ten years ago in the outer bailey of a border fortress by the English called Wark.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author of any book such as this is inevitably indebted to the work of numerous others, all of whom I have sought to acknowledge in the main text or in the notes and references. There is one authority, however, who merits a more prominent acknowledgement because without the benefit of Gerard A. Hayes-McCoys pioneering work on the galloglas these following pages would have been venturing into territory almost entirely uncharted.

In the more practical sphere of access to source material, I gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Stornoway headquarters of Western Isles Libraries most especially on the part of Mrs Margaret Martin and also of Inverness Reference Library. A word of gratitude is due to my friend Michael Robson for drawing my attention to a key passage in the writing of Martin Martin, as it is also to my publisher John Tuckwell who has borne generously with this project from its very first tentative proposal.

JM

PREFACE

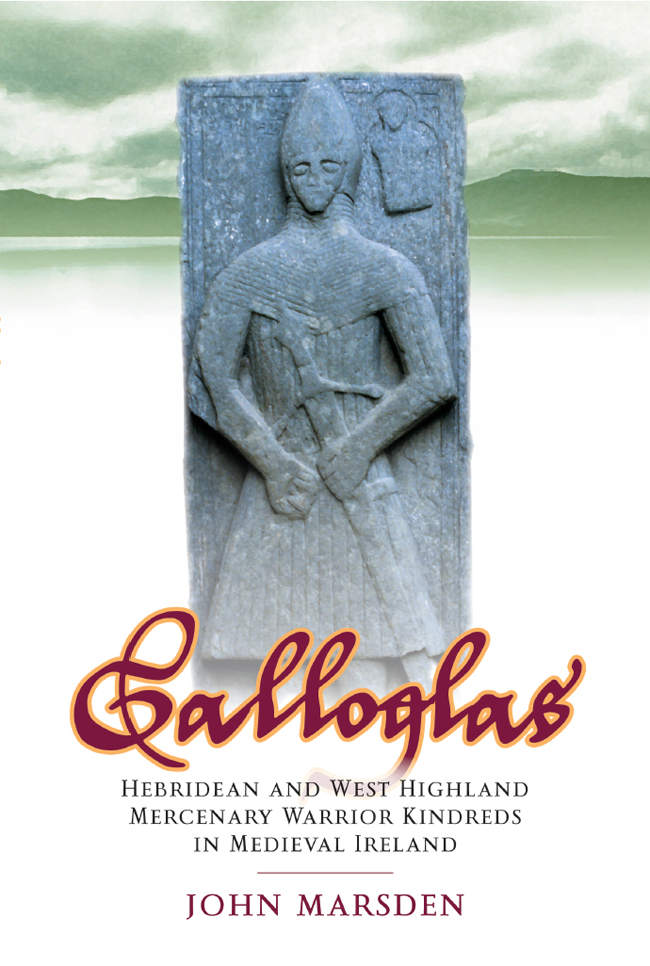

Thinking back now over the ten years since I first learned anything of the galloglas and at a time when I had no thought of writing a book about them so many things come to mind which would seem to have seeded themselves there as future sources of inspiration. One or two paintings by the fine military illustrator Angus McBride have long been fixed in the memory, and such time as I have spent in Ireland, although far too little, has left some sense of its landscape, accompanied by the music of its place-names, in there too. The prospect of the coastline of Antrim and Donegal seen across the North Channel from the Rhinns of Islay is always so clear in the imagination, but more haunting still are gaunt images of Gaelic warriors remembered from medieval grave-slabs throughout the West Highlands, and most especially from those in the roofless chapel at Kildalton.

In truth, though, it can only have been the preparation of my last book which somehow brought all those fragments together to inspire this new one, so there is good reason to introduce Galloglas as the natural successor (rather than any sort of sequel) to Somerled and the emergence of Gaelic Scotland. I have certainly come to think of it as such and not just because four of the six kindreds who form its subject were able to claim descent from the great Somerled of Argyll. The more important common ground shared by the two books lies in their reflection of my interest in the Norse component of the Celtic-Scandinavian fusion binding the deepest cultural roots of modern Gaelic Scotland. The previous book proposed Somerled as the historical figure most representative of the first fully-fledged emergence of that cultural fusion. This one will suggest the Hebridean and West Highland mercenary warrior kindreds who settled in Ireland in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries to make so remarkable an impact on the subsequent course of medieval Irish military history as a later if not, indeed, the last distinct example of that same phenomenon.

It was the eminent Irish scholar and politician Eoin MacNeill who first pointed to the importance of the galloglas in his Phases of Irish History

If these following pages can achieve even the most modest improvement on that sad situation, then their author will be well content, but it must be said that a detailed narrative history of the galloglas would require the collaboration of a team of Irish and Scottish scholars, including amongst them specialists in medieval genealogy and military history. Such a work lies beyond the resources of a freelance writer pulling in single harness, so this book will not attempt to scale any such heights. It sets out instead to offer an introductory account of the galloglas written from the viewpoint of their original homeland on Scotlands western seaboard and in the belief that their importance for Irelands history should not entirely obscure their significance in the story of Gaelic Scotland.

The preface to a book written in English on a Gaelic subject should include a note on the naming of names. After some thought and even at the risk of being considered inconsistent, I have decided to use the form of name which feels right to me in the historical context, just as long as it does not intimidate the reader with the more frightening excesses of medieval Irish Gaelic spelling. For example, the English form of Hugh is most familiar and seems quite suitable for the given name of the ONeill earl of Tyrone at the end of the sixteenth century, while the same name in its Gaelic form of Aodh feels more appropriate for an ONeill king of Ailech in the first half of the eleventh century. As a general policy, though, I have preferred to use the phonetic anglicised forms of Irish names and, wherever appropriate and helpful, to include the Gaelic or, in other instances, the English form in parentheses.

For the surnames of the galloglas kindreds I have used the anglicised Irish name-forms of MacSweeney, MacDonnell, MacRory and MacDowell for their members resident in Ireland, whilst retaining the Scottish forms of those names MacSween, MacDonald, MacRuari and MacDougall to distinguish their forebears and kinsmen in Scotland. MacSheehy and MacCabe although applied to kindreds of originally Scottish descent are names first occurring in Ireland and so do not present any such inconvenience.

With those necessary authorial apologia behind me, I press on in the simple hope that the reader who has survived thus far will remain sufficiently undaunted to continue in quest of these extraordinary axemen called galloglas...

JM

I

INTRODUCTION

From the Western Isles...

Although it seems most unlikely that the question has ever been included in any survey, my own suspicion is that the great majority of readers who know anything of the galloglas will have first come upon them by way of a passing reference in Shakespeares Macbeth, so perhaps that passage from the famous play might similarly serve as a port of entry here. It occurs at the point in the first act where the ominous gloom of the three witches gives way to a martial fanfare with news brought from the battlefield to King Duncan of Scotland and his son Malcolm:

... the merciless MacDonald

Worthy to be a rebel, for to that

The multiplying villainies of nature

Do swarm upon him from the Western Isles

Of kerns and galloglasses is supplied...

In view of the unfortunate discrepancy between the account of events offered by the Shakespearian tragedy and the real history of eleventh-century Scotland, it is hardly surprising that even these few lines from the play contain their own quota of anachronisms.